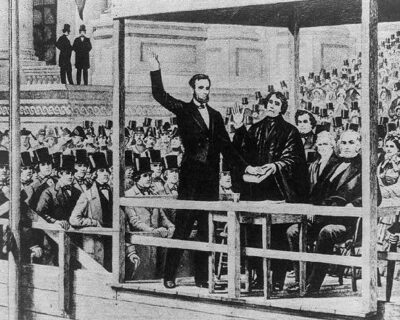

First Inaugural Address

By: Peter C. Myers

For many years a relatively minor figure in politics at the national level, Abraham Lincoln rose to prominence only in the late 1850s, largely on the strength of his performance in the 1858 campaign for the office of US Senator from the state of Illinois. Even after raising his stature in that debate and in subsequent speeches, he remained an improbable choice as the Republican Party’s nominee for the presidency in 1860. But once nominated, he was not an improbable victor, given the population advantage of the non-slaveholding states and the impending schism of northern and southern factions of the Democratic Party. Lincoln prevailed by a comfortable margin in electoral votes. Even if the electoral votes of the other three candidates had all gone to one, Lincoln still would have won the electoral college. Having won, Lincoln then faced the truly formidable challenges.

Lincoln acknowledged this the following February, as he headed to Washington for his inauguration on March 4, 1861. In his farewell speech to his hometown of Springfield, Illinois, the new president-elect remarked that the task before him was “greater than that which rested upon Washington.” The nation’s first president needed to establish the new national government on a firm footing of authority and thereby to solidify the union among the states, an enterprise fraught with great difficulty; but the sixteenth president had to restore the union in the face of a determined effort at secession that within five months after his election had spread over a third of the country. On December 20, 1860, South Carolina became the first state to enact a secession ordinance. Six more states followed by the first week of the following February, and the eight remaining slaveholding states were considering the question seriously. On February 4, 1861, delegates from the first seven secessionist states met in Montgomery, Alabama to proclaim the birth of the Confederate States of America.

Despite Lincoln’s victory in the electoral college, secessionists regarded his election as illegitimate. The general objection, as the South Carolina ordinance put it, was that for the first time in the nation’s history the presidency would be awarded to the candidate of a purely sectional party, running on an overtly anti-slavery platform. The election came in the wake of what slaveholding interests viewed as unconstitutional resistance by some northern states to the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and it empowered the Republican Party’s desire to prohibit slavery in federal territories—a position they held also to be unconstitutional, with support from the U.S. Supreme Court in the notorious case Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857). In affirming the power of constitutional secession, they acted pursuant to a doctrine Lincoln later labeled “an ingenious sophism,” propagated for decades by South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun and his acolytes.

Outgoing President James Buchanan reacted equivocally to the effort to dissolve the Union. In a message to Congress in early December 1860, he placed the blame for the conflict squarely on abolitionist agitation, even as he denounced secession as illegal. The secession theory, he maintained, was “wholly inconsistent with the history as well as the character of the Federal Constitution.” He added, however, that the Constitution delegated no power to Congress or the federal executive to compel a secessionist state to remain in the Union. After secessionists in the ensuing weeks seized federal forts and arsenals, Buchanan affirmed the federal “right and the duty to use military force defensively” against such acts but declared the situation, as a practical matter, “entirely above and beyond Executive control.” Only Congress, he maintained, possessed the power to meet the emergency.

In the meantime members of Congress were working on a plan of conciliation that became known as the Crittenden Compromise, named for Kentucky Senator John J. Crittenden, who led the effort. The plan comprised six proposed constitutional amendments that, among other things, would have restored and extended the Missouri Compromise line in the remaining federal territories and further protected slaveholders’ claims to fugitive slaves. President Buchanan endorsed it, although his own recommendations for placating slaveholding interests went significantly further. Lincoln rejected it. In a private communication he instructed U.S. Representative E.B. Washburne, Republican from Illinois, to “prevent, as far as possible, any of our friends from demoralizing themselves and our cause by entertaining propositions for compromise of any sort on ‘slavery extension.’” Acceptance of the compromise would have amounted to an agreement by Lincoln’s party, after being duly elected by the constitutionally prescribed process, to purchase its right to assume the presidency by surrendering the central provision of the platform on which it had campaigned. Lacking Republican support, Crittenden’s and all other compromise proposals failed in Congress, and the nation was left to await the incoming chief executive’s understanding of his powers and duties.

Lincoln was studying events closely and was wary of issuing any premature declaration of intention as to his policy. He told a Buffalo, New York audience in mid-February, “when it is considered that these difficulties are without precedent … it is most proper I should wait and see the developments, and get all the light possible, so that when I do speak authoritatively, I may be as near right as possible.” A few days later in Philadelphia he was more forthcoming, although he continued his silence regarding particulars. “When I do speak,” he said there on February 21, “I shall take such ground as I deem best calculated to restore peace, harmony, and prosperity to the country, and tend to the perpetuity of the nation and the liberty of these States and these people.” The following morning, he reflected in Independence Hall on the promise embodied in the Declaration of Independence—the promise “that in due time the weights would be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and all should have an equal chance”—and he pledged with bracing resolve: “if this country cannot be saved without giving up that principle … I would rather be assassinated on this spot than surrender it.” He reaffirmed his commitment to peace but added, “there will be no bloodshed unless it is forced upon the Government, and then it will be compelled to act in self-defence.”

The broad objectives Lincoln set forth as he traveled his winding route to Washington guided his composition of the speech he would deliver there upon his inauguration. Although he firmly rejected all proposed compromises that would tend to demoralize his supporters and delegitimate his party’s claim to power, he did not concede the inevitability of war. His broad objectives were to preserve the peace and to save the Union without relinquishing the principles of liberty and equality that made it, as he had said at Peoria in 1854, “forever worthy of the saving.” He was nonetheless clear-sighted about the possibility of a resort to arms. He framed his inaugural address as an endeavor to avert war, so far as honorably possible, and at the same time to maximize public support for the Union cause, in the event war proved unavoidable.

Divergent approaches remained conceivable. Lincoln could have taken a hard line against the secessionist states. He could have attempted to prevail upon them by direct intimidation, perhaps by a promise of war if they failed to repeal their disunion ordinances by a date certain. But he was unlikely either to intimidate or to persuade those already committed to secession; he needed more urgently to appeal to those slaveholding states that remained loyal and open to persuasion. A few months later he would remark, “to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game.” No less urgent, too, was the need to solidify pro-Union sentiment in the states to the north, divided along partisan lines as well as in their degrees of readiness to compel the slaveholding, secessionist South.

Instead of intimidation, Lincoln chose his own form of conciliation. He sought to persuade rather than to coerce, appealing to his straying fellow citizens’ sense of lawfulness along with their self-interest. He argued, as his predecessor had argued, that secession was unconstitutional and thus qualified as a revolutionary act, not a legal one. He argued further that secession was illegitimate as a revolutionary act, because secessionists could not cite as justification any clear violation of their constitutional rights. He advised that it was contrary to their professed interests, as it would make more difficult their recovery of fugitives and it would establish a precedent that in time would undo their effort to establish a new union among themselves. He appealed in closing to all Americans’ patriotic sympathies. But above all, he placed repeated emphasis on his constitutional oath as president, which constrained him from any aggressive act against slavery in the states—and also compelled him, contrary to the opinion of President Buchanan, to defend the Union against any attempt to destroy it.