Gettysburg Address

By: Jason Jividen

Among the several documents featured in this exhibit, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is the most famous. Memorized by school children, read and revered throughout the world, and inscribed—with his Second Inaugural—upon the walls of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., this short address of roughly 275 words is striking in its brevity, eloquence, and gravity. Scholars of rhetoric note the speech’s deliberate language, structure, style, and rhythm. Historians and biographers explain the context, timeliness, and influence of the speech. Political theorists study the ideas in the address, especially Lincoln’s claim that the nation is “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Often considered a turning point in the American Civil War, the Battle of Gettysburg took place from July 1-3, 1863. After a major victory at Chancellorsville, General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia sought to invade northern territory and surround the nation’s capital. General George Meade’s Army of the Potomac followed in pursuit. The armies met in southern Pennsylvania at the town of Gettysburg. After three days of intense fighting, Union forces won the battle, marking the northernmost point that Confederates advanced during the war. Combined with the successful siege of Confederate fortifications at Vicksburg on the Mississippi River, the battle of Gettysburg helped to shift the momentum of the war toward Union victory.

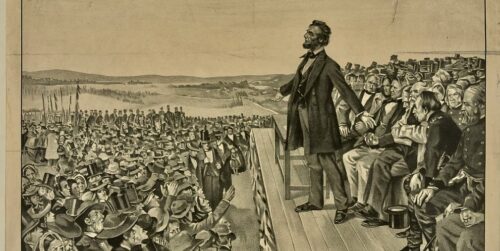

With more than 50,000 casualties, this was the bloodiest battle of the war. By October, some of the Union dead buried on the battlefield would begin to be relocated to Soldiers’ (now Gettysburg) National Cemetery, a portion of the battlefield consecrated on November 19, 1863. Invited to offer some remarks at the consecration ceremony, Lincoln delivered his Gettysburg Address, the opening of which contains one of the most famous sentences uttered by any American president. Immediately we should note that Lincoln dated the American founding to 1776 and the Declaration of Independence (four score and seven years ago) and, importantly, he suggested that the nation was at that moment “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” For some observers, Lincoln’s insistence that the Declaration somehow represents the American founding is debatable. Some claim that the founding is more reasonably dated to the writing and ratification of the Articles of Confederation or the U.S. Constitution. According to Lincoln, however, these frameworks cannot be understood properly in isolation from the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

For Lincoln, the notion that all men (i.e. human beings) are created equal was the bedrock principle of American government. In his speeches of the 1850’s, including his debates with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln routinely suggested that the equality of all human beings in their natural and unalienable rights is the founding principle of the American regime. For Lincoln, this natural equality serves as the moral and theoretical basis for government by consent of the governed and for majority rule. If all human beings—as creatures of the same species and rank—are equal by nature, then, whatever differences exist among individuals, no two of us are so different that our reason would suggest that one is a ruler by nature and another the natural subject. Thus, the only legitimate way one can claim a right to rule is through that other’s consent. According to Lincoln, any argument for self-government that denies these first principles is built on sand. This was the fundamental problem with Douglas’s “popular sovereignty” and Taney’s insistence on an indefeasible, constitutional right to slave property. For Lincoln, such positions were rooted, at bottom, in the tyrannical principle of might makes right, or the rule of the stronger.

However, historians and political theorists sometimes wonder about Lincoln’s claim that that the nation is somehow “dedicated” to this principle of natural equality. After all, some suggest, the Declaration of Independence does not say explicitly that the nation is dedicated to equality, or to any other abstract principle. Once again, we might turn to other documents to try to understand what Lincoln meant at Gettysburg.

Lincoln explained in his 1861 Fragment on the Constitution and Union that the animating idea of the American regime is the principle of “liberty to all,” or equal liberty. Echoing the language of Proverbs 25:11, Lincoln claimed that this principle was a word fitly spoken in the Declaration, a word that proved an apple of gold. The Constitution and Union are like a frame of silver meant to adorn and preserve the apple, the principle of equal liberty, which gives hope, enterprise, and industry to all. This is arguably what Lincoln meant in asserting at Gettysburg that the nation is dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. The Constitution and Union are meant to help realize and secure what is most fundamental, the equal liberty of all to pursue their interests, exercise their talents, and enjoy the fruits of their labor under the rule of law.

It should be obvious how all this speaks to the contradiction between chattel slavery and the principles of the Declaration of Independence. In the Dred Scott decision, Justice Taney claimed that, given their toleration of slavery, the authors of the Declaration could not have included black people in the phrase “all men are created equal.” The founders, Taney argued, believed that blacks had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect” and “might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery.” In response, Lincoln argued that, whatever differences or inequalities there might be among individuals, the founders declared all human beings—including slaves and free blacks—fundamentally equal in their natural and unalienable rights. For Lincoln, this meant that, as a matter of principle, a person ought to be able to eat the bread earned by the sweat of his or her own brow. According to Lincoln, the Founders “meant simply to declare the right, so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit.”

As Lincoln later declared in his July 4, 1861 Message to Congress in Special Session, for the Union, the war was “a struggle for maintaining in the world, that form, and substance of government, whose leading object is, to elevate the condition of men—to lift artificial weights from all shoulders—to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all—to afford all, an unfettered start, and a fair chance, in the race of life.” Whatever prudential compromises had been made with the peculiar institution out of necessity, the founders knew the practice contradicted the principles of the Declaration, and Lincoln always argued that the founders sought to place slavery on the path to ultimate extinction (see, e.g., his 1854 Peoria Address and his 1860 Address at Cooper Union).

These claims give us some context for understanding Lincoln’s suggestion at Gettysburg that the war tested whether a nation conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal, could long endure. For Lincoln, the American experiment was a novel one, and despite its compromises with slavery, it was dedicated to securing the rights of man with a faith in the people’s capacity for self-government. It served as an example to the world, and the crisis over slavery threatened the very existence of that regime. According to Lincoln, in order to preserve and transmit to future generations the regime handed down by the founders, the Union must finish the work of those who died at Gettysburg. They must win the war so that “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” The implications of Lincoln’s statements at Gettysburg were clear. A Union victory, and a “new birth of freedom,” necessarily looked toward the eventual abolition of slavery, which would ultimately require constitutional amendment. In the short term, however, it required emancipation and most likely the enlistment of freed slaves into the service of the Union army. Recall that the Final Emancipation Proclamation had been issued earlier that year. As many scholars have observed, along with some of the other documents mentioned above, the Gettysburg Address provided the moral argument for emancipation and abolition that was lacking in the dry, necessarily legalistic, and narrowly tailored Emancipation Proclamation.

Lincoln predicted that the world would little remember the things said at the consecration of Soldiers’ National Cemetery. Clearly, this is not the case with respect to his Gettysburg Address. However, we should note that Lincoln was not the main speaker for the day. That honor fell to renowned orator Edward Everett, who offered a very lengthy funeral speech before Lincoln took to the platform. Of course, many are today unfamiliar with Everett’s address. It is worth noting, however, that Everett apparently understood and appreciated the insight provided in Lincoln’s brief remarks. He wrote to the president the following day, praising the “eloquent simplicity” and “appropriateness” of his thoughts at the ceremony. “I should be glad,” Everett wrote, “if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”