Lincoln’s Address to the Young Man’s Lyceum “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions”

By: David Tucker

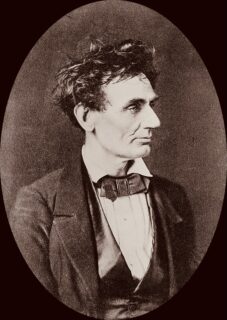

Benjamin Franklin famously told an enquirer that the constitutional convention had given Americans a republic, if they could keep it. Engaged in an unprecedented political act, the founders were aware how precarious their endeavor was. Historical examples canvassed thoroughly by James Madison, but to some degree generally known, suggested that perpetuating a republican government was more difficult than establishing one. About 50 years after Franklin’s remark, in January, 1838, a young lawyer and representative in the Illinois legislature took up the issue of perpetuating republican government. Abraham Lincoln, 29 years old, spoke at the Springfield Lyceum, an organization that sponsored speeches, debates, dramatic readings and other educational activities. The first Lyceum was set up in the 1820s and was soon imitated. Lyceums spread throughout the United States, although they were most prevalent in the northeast and midwest. A Lyceum was the sort of place where an ambitious young Illinois politician would want to give a speech.

As Lincoln explained in his address to the Lyceum, he believed that the survival of the republic was at issue because a “mobocratic spirit,” as he put it, was loose in the land. His analysis was more complicated than that, however. Lincoln considered the roles that both the people and the ambitious few played in the drama of republican survival, as well as contemporary and enduring threats to republican government. He also suggested remedies for the threats and, in doing so, raised questions about the relationship between reason and the passions. That relationship, he argued, affected the likelihood that republican government—self-government—could survive.

As Lincoln’s analysis is complex, so is the structure of his speech. The Lyceum Address consists of a brief introduction (paragraphs 1–3), two long central sections, the first focused more on the contemporary threat to the American Republic (paragraphs 4–15), the second more on the enduring threat (16–23), and a brief conclusion (paragraph 24).1 Lincoln indicated the two sections by starting each with a version of the same question and giving each section a structure the inverse of the other. Paragraph four begins “At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected?” Paragraph 16 begins “But, it may be asked, why suppose danger to our political institutions?” The first section discusses the passions of the people and their lawlessness, and then mentions the few who might exploit that lawlessness to destroy self-government. The second section inverts this relationship, beginning with a consideration of the ruling passion of what we might call the historically few (Alexander, Caesar, and Napoleon) and then discussing the passions of the people. The remedy in the first section, which focuses on the people, is political religion, although Lincoln acknowledges that there are instances in which obedience to the law is not all that is required because there are bad laws that need to be changed. The remedy in the second section, which focuses on the ambitious few, is “cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason.” We may connect the remedies in the first and second sections of the speech by asking if it is not reason, “cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason,” that must tell us when obedience to the law is not enough.

If we consider the sections of the speech in more detail, we see that in the first section Lincoln argued that the American people in the 1830s were disregarding the law and substituting for it the rule of what he called “the wild and furious passions,” and that men of talent and ambition could exploit this situation to overthrow republican government. (Historians have claimed that there was more mob violence in America in the 1830s than at any other time in American history.) The second section begins by considering men not just of talent and ambition, those who might be satisfied with being President, but those of towering genius and ambition, who could not be satisfied with any merely republican honor. If such a person arose, Lincoln argued, the people would need to be united to resist the threat he posed. Lincoln went on to explain, however, that this unity would be difficult because of the passions “incident to our nature,” or as he also said, “the basest principles of our nature.”

In the first section of his speech, Lincoln described the mechanism by which republican government could be lost in some detail. He distinguished between the direct and the indirect effects of lawlessness. The direct effect is lynching. The indirect and worse effect was that such brutal lawlessness would make good people lose faith that government could protect what was important to them—indeed, to doubt that republican government was good for anything. If this occurred, the people would see little reason to defend the government when it was threatened by a man of talent and ambition. Indeed, they might think that government by a strong man was better than self-government.

In the second section of the speech, Lincoln did not describe in any detail how the man of towering genius and ambition, aided by the basest passions of the people, would overthrow the republic. He did cite three historical examples, however: Alexander, Caesar, and Napoleon. All three were military geniuses who helped turn republics into empires. They extended power over other nations and then, having forced other nations to submit, demanded that their own submit as well. Divided by their base passions, Lincoln suggested, the people would be unable to resist towering ambition.

Despite their differences, both sections of the speech show a similar route to republican ruin. In the first section of the speech, the “wild and furious passions” of the people create lawless mobs that breed indifference to the fate of the republic. In the second section of the speech, the lawlessness typical of men of rare ambition, which is “their ruling passion,” takes advantage of the typical passions that divide the squabbling people to overthrow the republic. Lawless passion is the theme that unites the two sections. Recognizing this, we may well wonder if in the passionate nature of their lawlessness there is much difference between the people and the few.

Having seen Lincoln’s analysis of the threat to republican government, a reader may wonder at how adequate his remedies are. Political religion, the remedy in the first part, is reverence for the laws and constitution. Lincoln said such reverence is to be taught everywhere and that all Americans should “swear by the blood of the Revolution never to violate in the least particular, the laws of the country.” But in acknowledging that there are bad laws that need to be changed, is Lincoln not acknowledging an attitude toward the laws that is something other than simple reverence?

Lincoln seems to amend or amplify his advice about political religion at the end of the second part of the speech. There he remarked that “passion has helped us; but can do so no more. It will in future be our enemy.” During the revolution, the passions of the people were bound up and directed to a good end—defeating Britain and establishing a republic—but that work is done. No longer directed to a good and transcendent end, popular passions were rudderless and the people thus prey to a man of towering ambition. The remedy Lincoln proposed for this illness was a reliance on calculating, unimpassioned reason, which would furnish materials from which will be molded new pillars for the temple of liberty: “general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws.” One would like to ask Lincoln some questions. First, what are the materials you are talking about and how does calculating reason furnish them? Second, who then molds these materials into the new pillars of the temple of liberty? Lincoln suggested that “a reverence for the constitution and laws” was the most important of the new pillars. “Reverence” recalls political religion, the remedy offered in the first section of the speech. But is not reverence a passion? Passions were no longer supposed to help us. And if this passion is still helpful, can reason, “cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason,” generate the passion of reverence?

Instead of elaborating on the remedies, Lincoln closed his speech by invoking the name of Washington and by quoting the Bible. If freedom rests upon the new pillars, we may say of our republican government, as of the only greater institution, “the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.”2

The rhetoric of Lincoln’s speech served the public good by stigmatizing passion-driven lawlessness and encouraging a reasoned respect for the law. Within this rhetoric, however, Lincoln raised questions that he would deal with for the remainder of his life.

1 Paragraph numbers refer to the paragraphing in the version of the Lyceum Address found in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy Basler (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), vol. I, 108–115.

2 Matthew 16:18.

| Previous Essay | Home | Next Essay |