From Bullets to Ballots: The Election of 1800 - Ch. 6

The Republicans Persuade

- The Campaign and Elections of 1792

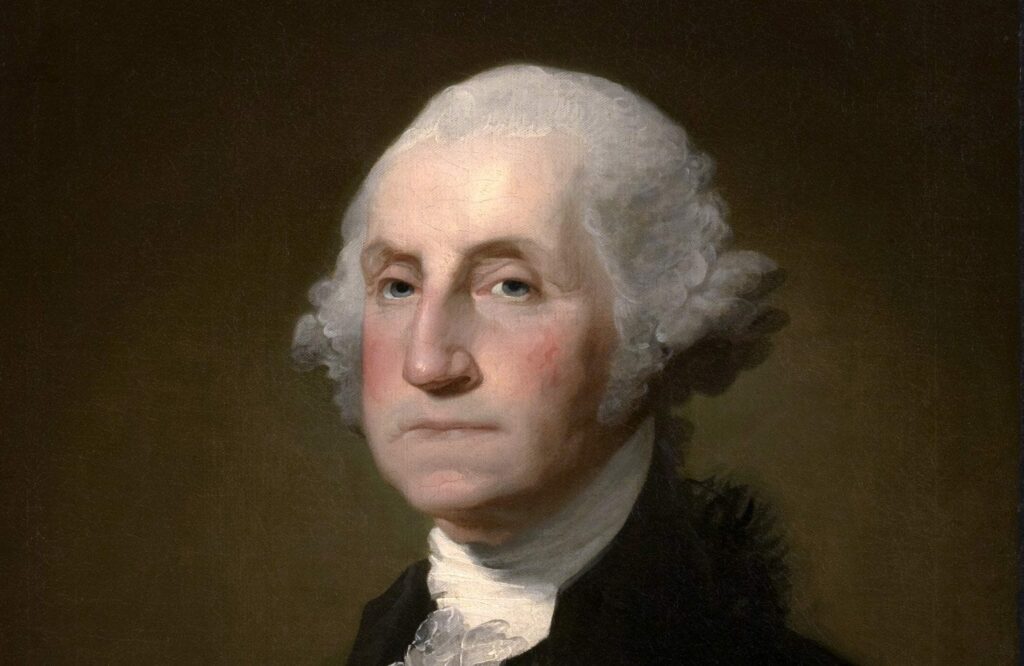

- The Problem Of George Washington

- Hamilton’s Innocence and Guilt

- Economic Reality and Political Rhetoric

If truth is not a necessary casualty of party warfare, it is (as Winston Churchill remarked when speaking of war pure and simple) sufficiently precious that sometimes it must be surrounded by a bodyguard of lies. One of the common features of partisan politics is that certain things come to be talked about with profitable imprecision, and this is no less true with parties of principle. Opinions are misrepresented for partisan advantage. Powerful but partial slogans and sound bites are coined. Similarities are denied. Distinctions are blurred.

One of the distinctions that the Republican party of the 1790s sometimes blurred in order to advance its popularity was that between the allegedly anti-republican, “monarchical” character of Hamilton’s fiscal policies and the more straightforward antirepublican position of defenders of hereditary monarchy and aristocracy. John Adams, who in fact found Hamilton politically and morally suspect, and was not a fanatical supporter of Hamilton’s fiscal system, nevertheless was placed by Republican writings into the same frame as Hamilton. Republicans portrayed Adams as an advocate of hereditary forms of government. Adams was in truth no such thing. Nevertheless his falsely-alleged monarchism was used in a fallacious way as evidence to prove the monarchical intentions of Hamilton. Of course, Hamilton himself was known to have spoken in the secret debates of the Constitutional Convention in favor of considering life tenure for presidents, and Republicans did not fail to draw attention to this when accusing Hamilton of monarchism. But there is a great difference between tenure for life (or for “good behavior”) and hereditary offices: as Madison’s Federalist Number 39 points out, tenure for good behavior in some offices is fully compatible with republican government. So if Adams could be convicted of favoring hereditary offices, he would be a more vulnerable target than Hamilton for Republican suspicions about the promotion of monarchism.

Hamilton’s economic “monarchism” seemed to Republicans to be more dangerous than political monarchism, because it was less open and avowed, and therefore less immediately vulnerable to attack. The insinuating crypto-monarchism of Hamilton consisted of the unrepublican spirit of speculative profit-making at the public expense, made possible by fiscal policies that in turn had been enacted only because the Treasury scheme’s corruption of a sufficient number of representatives had prevented the wishes of the people from being followed or even from being consulted. Economic monarchism was an attempt to transplant the corrupt and corrupting British way of governing into the heart of the American republican regime, and it was dangerously close to succeeding, because of popular inattention to the danger. Or so the Republicans believed, and so their story went.

Adams’ reputation on this subject dated back to 1789, when he, as vice president (presiding over the Senate), together with an Anti-federalist Senator from Virginia, led the Senate to agree to honorific forms of address for the highest elected officials in the new government (e.g. “His Highness” the President). This would have embarrassed Washington had it been approved. The House of Representatives had decided to reject any such idea, and to address Washington simply as “President of the United States.” The Senate soon agreed with the House, and the matter was settled. However, Adams’ support for titles—which he thought would have been perfectly republican and quite useful in enhancing the dignity of the republic at home and abroad—got him into trouble with a press and a people for whom the universal fashion was for republican simplicity, and earned him a great reputation for anti-republicanism. (The fact that Adams had sons—unlike Washington, Jefferson, Madison, or indeed any other president until Andrew Jackson—may have added some plausibility to the absurd idea that Adams hankered after hereditary monarchy. In 1800 there was even a rumor that he had tried to get one of his sons married to one of King George III’s daughters, to set up an American royal dynasty!)

In 1790 a French diplomat in America reported that Adams’ part in the debate about forms of address, plus Adams’ criticism of the French Revolution, had made Jefferson rather than Adams into the heir apparent to Washington—a premature conclusion, but ultimately not all that inaccurate. In a series of articles in the Gazette of the United States in 1790 and 1791, Adams criticized constitutional developments in France for their too hasty and too levelling egalitarianism and for their rejection of such prudent constitutional arrangements as bicameral legislatures. At this time many Americans were still looking on revolutionary France as a republican soul mate, so there was potential for Adams’ articles to make him more unpopular. In fact, he expected they would.

What most helped actualize that potential was a step taken—inadvertently, it seems—by Thomas Jefferson, in an incident that was the first stage in the breakup of the friendship of Adams and Jefferson. Jefferson’s praises for Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man were published (without Jefferson’s intention) as a blurb in the first American edition of that book. Paine’s book defended the rationality and justice of the French Revolution against the attack by Edmund Burke’s Reflections on it, and denounced the intrinsic injustice of all hereditary forms of government. Jefferson noted that he was “extremely pleased to find … that something is at length to be said publicly against the political heresies which have sprung up among us”—an undeniable reference to Adams’ articles, and an offensive and false assertion that they were lapses from the republican faith. (Jefferson probably had not even read Adams’ articles.) Newspapers everywhere picked up this sensational conflict between the Vice President and the Secretary of State. Jefferson wrote a soothing letter to Adams, but did not stop his misrepresentation of Adams’ views, even though Adams immediately challenged Jefferson to find a single passage in his public or private writings that could be interpreted to mean that he favored the introduction of hereditary government in the United States. Jefferson never responded to Adams’ challenge. In fact, in their correspondence after they had both retired, Jefferson admitted that he and other Republicans had attacked Adams during his presidency for views that they did not even believe he held. To Jefferson, misrepresentation was a fair partisan tactic.

This abuse of Adams’ writings, and the more general debate about the emergence of republicanism in France, enabled Republican propagandists to link Hamilton’s economic policies with the political monarchism and aristocracy that Adams was mistakenly believed to favor and that Edmund Burke and other English critics of Revolutionary France and defenders of Britain clearly did favor. Republicans could enjoy greater credibility in their attacks on Hamilton’s project as economic antirepublicanism if they could argue that it was of a piece with a less indirect and a clearly evident political anti-republicanism. Being able to say—inaccurately, but credibly—that political antirepublicanism was being openly avowed even in high places in American government strengthened the force of their argument that Hamilton’s policies were intended to lead on to the introduction of hereditary forms of government.

The Campaign and Elections of 1792

Finding the Media for the Message

Technologies have changed, but the close connection of politics and the media was not an invention of the twentieth century, it was an essential tool of modern political parties from the very beginning. The Revolution of 1800 was built on communication networks among those actually or potentially sympathetic to the Republicans’ revolutionary goals. The Republican leaders were skillful media managers. At least one Republican even organized and published the results of public opinion surveys, as well, completing the modern campaign circle linking candidates, parties, public opinion, and communications media. Republicans did not hesitate to use “negative” campaigning in the media, raising doubts about the character of their opponents when this was appropriate; after all, they were asserting that Hamilton’s policies were a conscious imitation of corrupt and antirepublican English fiscal politics, and that assertion had to make Hamilton and his allies look bad. Hamilton and other Federalists soon responded in kind.

As in the Revolution of 1776, one important medium of communication was letters circulating among the partisans, very often copied by the recipients to others, and sometimes also published in the press. In the revolutionary resistance against Britain, “committees of correspondence” had been a key part of the patriots’ efforts. If Thomas Paine had become United States Postmaster General, which was Thomas Jefferson’s suggestion to President Washington in 1791, his holding that position would surely have had practical as well as symbolic political significance, both in terms of patronage and in terms of controlling this medium. (Later in the 1790s, Jefferson and others would sometimes feel obliged to avoid using the post office to carry their letters, fearing divulgence of their contents to party rivals.)

Pamphlets and newspapers were also important in both Revolutions. Americans recognized that public opinion is more powerful in republics than in non-republican regimes, and that a free press is therefore crucial in republics, for the enlightenment of public opinion. So they would have understood Jefferson’s statement (in a private letter, and typically exaggerated) that it would be far preferable to have newspapers without a government than government without newspapers. Newspapers greatly proliferated throughout the United States in the 1790s, and became the major medium for partisan campaigning. Jefferson’s and Madison’s bringing Philip Freneau to Philadelphia to set up his newspaper was an excellent way both to nationalize the Republicans’ concerns and opinions, and to spread the conflict from congress to the American people in every state. Not without reason was the paper called the National Gazette. Unlike the daily Philadelphia newspaper that the Republicans could have used for their purposes, the National Gazette was a weekly, and therefore (as Jefferson said) “likely to circulate through the states.” Starting with the campaign of 1792, fiery Republican polemics, followed by Federalist responses, first appeared in newspaper articles in the capital (Philadelphia), then were circulated and reprinted across the country, supplementing or inspiring local newspapers sympathetic to the Republicans’ cause. This pattern was repeated during subsequent campaigns in the 1790s. (Although the National Gazette itself fell victim to yellow fever and shortage of funds, the Philadelphia Aurora replaced it as the main Republican paper in the capital.) Even in New England, the toughest nut for the Republican party to crack, newspapers from the middle and southern states circulated with increasing regularity, and in the latter part of the decade some local Republican presses were set up there as well.

The Campaign Begins

As every media consultant knows, timing is important, as is an element of surprise. The Republicans’ first journalistic polemics were strategically focused on the elections of the autumn and winter of 1792-1793 that would determine the composition of the third congress (scheduled to convene in December 1793). The Republicans took the initiative in attacking the Federalists, whose own media resources and skills then took some time to prepare, and never matched the Republicans’. The Republican media initiative was also intended to complement continuing efforts to defeat Hamilton’s project, or at least to put him on the defensive and to harass and to embarrass him, during the remainder of the second congress. Several months of relative calm in editorial opinions in Freneau’s new National Gazette as well as in Fenno’s older Gazette of the United States were broken by a series of partisan pieces by various writers, which started appearing in Freneau’s paper at the end of February 1792 and continued for the rest of the year. These articles were unprecedented in their number and in their partisan vitriol. Before then, Freneau’s new journal had been politically circumspect. Fenno’s, always sedate, had become even more mellow since moving with the capital from New York (where he had been antagonized by an Anti-federalist paper) to Philadelphia; Fenno had even published a few articles against the national bank. Now Republicans politicized the press.

Republicans attacked with National Gazette articles that pilloried Hamilton’s funding system and the excise tax for their unrepublican character, and advised readers that although the proposal for honorific titles had been defeated two years ago, antirepublican principles were still in the air and on the ground. The funding system was blamed for having inspired an excessive “thirst for rank and distinction” in America. Steered by the funding system, one writer warned, “Our political bark seems to be gently sliding down that stream leading from freedom to slavery.”

Fenno, caught by surprise by this initial onslaught, eventually responded with articles in his Gazette charging the National Gazette writers with the sins of Anti-federalism and electioneering. The Republican writers shot back that it was not a question of Federalism or Anti-federalism, it was “the Treasury of the United States against the people.” As for electioneering, well, yes (Freneau himself wrote), they were a kind of “faction,” but he did not mean that they were at all the kind of faction that Madison had been so suspicious of in The Federalist, since they comprised “a very respectable number of the anti-aristocratical and antimonarchical people of the United States”—including, although in principle anonymously, Congressman Madison. The construction of a respectable party of principle was underway. The first step was for respectable politicians and citizens (not just more easily dismissible poetic journalists) to publicize respectable principles that attacked current government policies.

While this newspaper warfare was underway, Hamilton was having a hard time of it in congress, too, where further elements of his project (fishery subsidies, new taxes) continued to be approved, but with smaller majorities, and with little promise of enough momentum to carry through to what was to have been the third major stage, the systematic encouragement of domestic manufactures that Hamilton had recommended in December 1791 in his Report on Manufactures (and which was never taken up by congress). Ominously, congressional opposition to Hamilton’s project by those who were prepared to be associated with the “respectable … anti-aristocratical and anti-monarchical” party now included not just disgruntled Anti-federalist diehards but also Hamilton’s principal congressional antagonist, James Madison. Madison now began to attack Hamilton not just on the ground of fairness or constitutional construction—that was bad enough—but also on the ground of the anti-republican bearing of Hamilton’s schemes. In March 1792 Madison reminded the House of the Virginia Resolutions of 1790, with their criticism of funding and assumption as English and unrepublican. Madison had joined other congressmen in quietly ignoring these Resolutions when they had arrived in congress fourteen months before. But now “Little Jimmy” Madison, the political heavyweight and eminently respectable Federalist, had begun to play the Anti-federalist, country ideology card, in order to help create the Republican party’s more liberal, more national, and more optimistic rhetoric.

Madison on Public Opinion and Parties

If further confirmation were needed that Madison was one of the new Republican party, his own eighteen National Gazette articles would do nicely. These appeared from November 1791 to December 1792. They repay careful study, even though they are brief, unsigned, partisan newspaper polemics. Their arguments call for comparison with Madison’s Federalist essays (which of course were also unsigned partisan newspaper polemics, although they were longer, more elevated and elaborate, and, running to 85 numbers, more numerous—“the dry trash of Publius in 150 numbers” had been one contemporary putdown!). In these Republican party pieces, Madison did not completely reverse his Federalist thoughts on republican politics and parties. However, he expressed some very important amendments and developments, which can help us think about the creation of party government that Madison is here both engaging in and reflecting on.

Madison’s newly-vivified concern with the form, formation and function of public opinion leads him to some important differences of emphasis. Madison stops emphasizing the need to energize the central government, and starts emphasizing the need to strengthen the influence of public opinion on government. As we have seen, bringing public opinion to bear on government policy is what Jefferson and Madison had already privately suggested in 1791 as their chosen method of turning back Hamilton’s influence. Madison now publicly calls for enabling “the great body of the people” to “interpose a common manifestation of their sentiments.” In an article on “Public Opinion,” Madison clearly spells out the main disadvantage of an extensive territory, which can be “unfavorable to liberty” because it can make each individual “insignificant … in his own eyes.” The republican (and Republican) remedy for this is to “consolidate” not the government but “the affairs of the states into one harmonious interest,” and to erect an “empire of reason, benevolence, and brotherly affection” over “the various authorities established by our constitutional system.”

Before, in The Federalist Number 10, Madison had emphasized the advantages not only of an extensive territory but also of economic and social heterogeneity (having more factions makes them less threatening to just and wise statecraft). Now, in his National Gazette essays he emphasizes the advantages of social homogeneity in the sense of a consolidation of “interests and affections,” and calls for a greater “concord and confidence throughout the great body of the people.” He pleads for facilitating “a general intercourse of sentiments,” by means of “good roads, domestic commerce, a free press, and particularly [he emphasizes] a circulation of newspapers through the entire body of the people, and Representatives going from, and returning among every part of them.” The contrast between Madison in 1787 and Madison in 1792 is not absolute. For example, in The Federalist Number 14, in order to assure his readers that the United States was not too large for republican government, Madison had cited the existing and steadily improving means of transport; he does not there mention the circulation of newspapers and representatives’ consultations with their constituents, but he does note the “many cords of affection” that knit Americans together. However, there is clearly a large change of emphasis, obviously based on the fact that in 1792 Madison is concerned with finding a way of mobilizing enough public opinion to help him challenge the government’s policies.

In spite of these important changes, Madison has not reversed his views on political parties. The Federalist does not anticipate, but neither does it rule out, the possible usefulness of a majority party of principle of the kind that Madison was building and justifying in 1792. Nor, according to The Federalist’s arguments, will the large republic pose insuperable barriers to a majority party of principle, in the way that it does to any majority party of interest (a majority faction). Compared to a small republic, a large, diverse republic has “greater obstacles opposed to the concert and accomplishment of the secret wishes of an unjust and interested majority.” The greater difficulty of communication in a large country will help keep the unjust projects of factions “secret,” because factions, being based on “a consciousness of unjust or dishonorable purposes”—and therefore wanting to keep their motives hidden—will be less able to engage in public discourse than a party that is based on a consciousness of just and honorable purposes. The difficulty of organizing a majority party of principle should therefore be much less than that of organizing a majority faction. It would be unfortunate if the need to do so were to arise, for that would mean that government policies had gone gravely wrong, and opposing the government might require courage and cause trouble. But one would not have to feel uncomfortable about the right to do so, which in fact was a duty as much as a right, for The Federalist as well as for Madison in 1792.

Of course, any good party of principle will also be a party of interests, because otherwise it will not be able to do any good. A successful party has to have body as well as soul. Any successful modern political party will have a network of supporting interests as well as policy commitments based on principles. One of the lessons of the 1790s is precisely the necessity of having both of these elements if a political party is to be effective. Opponents of the new Republican party were able to point out that it involved an alliance both of certain states (notably Virginia and New York), and of certain interests (not just farmers but also various commercial and manufacturing interests that felt excluded from Federalist circles). But it is impossible to conceive how these various interests could have come together into the effective Republican party unless that party had also thought of and presented itself primarily as a party of principle, not merely an assembly of interests or factions. This principled side has always been essential to great political parties, and it is especially evident in their origins, when they are assembling themselves for their first

battles.

New Campaign Issues

Hamilton did not reply to the Republicans’ spring media offensive until the middle of the summer. Then he took up his pen and began to accuse his accusers. Writing in the Gazette of the United States under various pseudonyms, he cited facts to prove that the Treasury had not been guilty of unnecessarily increasing the debt. However, he did not make a sustained positive case for his financial-industrial project. He quickly went on the offensive against Jefferson (he“went negative”), but not very effectively. He simply repeated and elaborated Fenno’s charges of Anti-federalism and partisanship (charges that National Gazette writers had already effectively responded to). On the Anti-federalism charge, Hamilton raked up old issues on which in any case Jefferson’s conduct was not culpable: he accused Jefferson of having been a lukewarm supporter of the Constitution—an accusation that was at best misleading. He also accused Jefferson of having displayed a deficient sense of the need for the federal government to establish its credit when he was minister to France back in 1786. This was false, and Jefferson made short work of it when writing to President Washington about Hamilton’s accusations. On the real issue of the day, Hamilton accused Jefferson of having put Freneau onto the payroll of the Department of State so he could set up a newspaper that was a political mouthpiece of Jefferson, the Secretary of State. This last accusation was substantially true, and Jefferson’s attempts to explain it away in his letter to Washington were resourceful but unconvincing. But Jefferson did not regard his principled partisan opposition to Hamilton (the purpose of his establishing Freneau) as anything but laudable. And in any case, he was able to point out to Washington that the cabinet officer who had actually personally written partisan squibs in a national newspaper was not he, but Hamilton (anonymously, but transparently so). Hamilton had not done the dirty work very well, and he made the mistake of doing it himself, which enabled Jefferson plausibly to portray Hamilton, not himself, as the one who was the bad cabinet colleague deserving Washington’s censure.

In the autumn, the Republican newspaper campaign, in the New York Journal as well as in the National Gazette, made John Adams rather than Alexander Hamilton the chief target. In all probability, this was a sign that the media campaign was again being intentionally focused on electoral goals, since party leaders had just decided to try to replace Adams as vice president with Governor George Clinton of New York. (Madison had opposed Clinton’s candidacy for vice president in 1788 because of his Antifederalism). Clinton’s winning this office would have been helpful for the Republican cause, since (as Jefferson would find from 1797 to 1801) the vice president’s job of presiding over the Senate meant he would immediately be privy to secret Senate proceedings. But even if the Republicans did not really expect their efforts to unseat Adams to be successful, these efforts were nevertheless a way of inspiring and maintaining support for the Republicans’ cause.

The Election Results

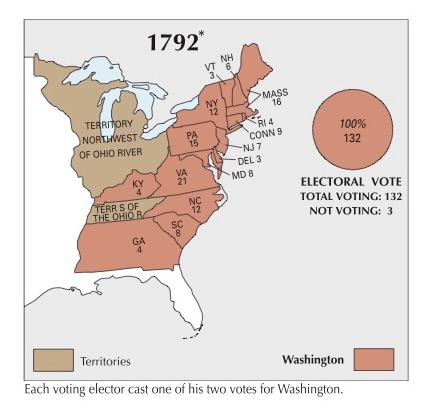

By December it was clear that Adams would retain his office. In the event, it was Adams 77 to Clinton 50, with Clinton getting all of the second votes of New York, Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia. (There were also 4 votes for Jefferson and 1 for Burr.)

Elections to the House of Representatives had always seemed to the Republicans to be more important than the vice-presidential race. Party loyalties and labels having just sprung up, it was not possible to count exactly what the party balance in the next House would be. Besides, that congress would not meet until December 1793, and the minds of congressmen elect could be changed by many events during the intervening months. (Indeed, 1793 did introduce some momentous new issues.) However, when the results were in, they thought they had done extremely well, especially in New York and Pennsylvania. Even before all the elections were over, Jefferson saw (in December 1792) “a decided majority in favor of the republican interest.”

As for the presidency, there was no question but that Washington would be re-elected if he did not retire, and he was unanimously re-elected. He had talked to Madison, Jefferson, and Hamilton about his desire for retirement, but did not announce it, and by the autumn it was just assumed that he would be available. In December, Freneau’s newspaper turned for the first time to direct criticism of Washington; in February it scorned the splendor of his birthday celebrations, and, in March, when Washington’s second term of office began, Freneau suggested that Washington make his second term less courtly. Apparently some Republicans hoped that their victory in the congressional elections would persuade Washington to join them in opposing Hamilton’s projects.

However that might turn out, there was little chance of Washington approving of the Republican press campaign. An avid reader of newspapers, he was not pleased by their recent turn towards partisanship. Well before Freneau’s newspaper dared to start criticizing the President himself, Washington was of the firm belief that the criticism of government officers and policies that was being published in Freneau’s newspaper was threatening to destroy the Union. Jefferson was certain that the opposite was the truth. In May 1793, after the election results were known, Jefferson recorded in his private notes his belief that Freneau’s “paper has saved our Constitution, which was galloping fast into monarchy, and has been checked by no means so powerfully as by that paper. It is well and universally known, that it has been that paper which has checked the career of the monocrats.”

The Problem Of George Washington

Washington’s opinion on the quarrel between the Republicans and Hamilton mattered to Jefferson, for party as well as for personal reasons. In addition to the Republicans’ continued attempts to defeat Treasury policy in the congress elected in 1790 (which they did not expect to succeed, and which did not), and to their electoral campaign (in which they placed much more hope, and which they thought was succeeding), there was a third, less public front in the Republicans’ efforts in 1792: they—in particular Jefferson—had to deal with the problem of George Washington’s immense reputation and presidential power, which were acting as barriers to changing the government’s policies, both directly by Washington’s not criticizing Hamilton and indirectly by his criticizing the views of the new Republican press.

Jefferson had a series of conversations and exchanges of letters with Washington from February through October 1792, and kept Madison informed about these. The Republican leaders probably had several motives in these exchanges with the President. If they could not reasonably hope to get him on their side, perhaps they could nevertheless hope to weaken his support for Hamilton. Failing even that, their efforts might at least prevent Washington from turning against them; maintaining Washington’s neutrality and even-handedness towards his quarrelling cabinet officers was worth something. If nothing else, it might goad Hamilton into making mistakes: Hamilton’s ill-thought-out journalistic response to the Republican newspaper campaign against him was probably in part a response to having just received a letter in which Washington had presented to him a long catalogue of the charges that Jefferson was making against him. Finally, there is the fact that Washington was considering retiring (i.e. not being available for re-election). Jefferson sincerely told him that he hoped he would remain as president (as did Hamilton, of course!). If he had retired, the Republicans would have faced the difficult question of whether and how to contest John Adams’ elevation from the vice presidency. All in all, the Republicans had nothing to lose and some possibilities of gain from Jefferson’s maintaining good relations with the President.

However, they clearly did not persuade Washington to join the Republican cause. In conversations and letters from February through May, Jefferson explained to him how Hamilton’s policies produced barren, immoral speculative activities, and asserted that they had passed only because the funding of the debts had supplied the means of “corrupting such a portion of the legislature as turns the balance between the honest voters.” By this, Jefferson meant that congressmen with private interests in government loan stocks had been influenced by this fact rather than by their constituents’ interests or wishes, when voting for Hamilton’s policies. But by the end of August, it was clear that Washington was not in agreement with this Republican view. He stopped getting involved in the details of his cabinet’s quarrels (as when he had catalogued Jefferson’s charges and presented them to Hamilton). Instead, he wrote letters to each of the quarrelers (Randolph as well as Jefferson and Hamilton), asking that they

treat each other with greater charity, make liberal allowances for differences of opinion, and make mutual accommodations and “yieldings.” In other words, Washington did not agree that there was any uncompromisable difference of principle, did not take sides, and did his best to suppress rather than to settle the partisan differences.

It is true that he came down the hardest on Jefferson, to whom he denied that it was reasonable for any member of the administration to oppose agreed-upon measures (e.g. the funding system) before their utility had been given a fair trial. In this remark to Jefferson he was echoing Hamilton’s response to Washington’s catalogue of Republican accusations, that only “experience” could show whether the dire, theoretically-based predictions of the accusers would come true (and that experience to date had shown they had not yet come true): although the birth of America’s new public finance system was accompanied by rational speculation, and even by irrational speculative bubbles, these were very temporary effects, not durable and intrinsic features of the system. While it was not logically or physically impossible that the system might lead to unrepublican government, there was no sign of this happening yet, so the Republicans’ predictions had no basis in Americans’ practical experience. Neither was the Republicans’ accusation that a few congressmen had been preferring their own interests to their constituents’ wishes when voting for Hamilton’s projects any more than a speculative hypothesis. On this point Jefferson would have had to agree: only time—and future elections, after campaigns explicitly seeking voters’ reactions to these projects—would tell.

But Washington also called on Hamilton to remember that no mortal is infallible, and that it cannot be helpful to make wounding and irritating charges in the newspapers. He saw nothing but disadvantages in the emergence of partisan politics and its vicious ways. He did not see how the growing partisan conflict could be anything but a liability for the American experiment, and a threat to this “fairest prospect of happiness and prosperity, that ever was presented to man.”

Getting the acceptance of partisanship to be fully recognized as an asset rather than a liability for American democracy was the work of several decades, but the work got well underway in the 1790s, against Washington’s advice. Washington’s greatness was an incalculable asset for America as an emerging democracy in a hostile world, but was also a barrier to the addition of party government to American democracy. As in other new democracies, there was a powerful general opinion that serious partisan opposition to the revolutionary regime and to its prime champion must be bad. Washington’s grandeur as president supported that opinion. So did his retirement from the presidency, which was accompanied by a “Farewell Address” (printed in the press, never actually given as a speech) in which Washington warned against “the baneful effects of the spirit of party,” especially in republics.

However, insofar as Washington’s presidency was a kind of republican monarchy, Washington’s Farewell advice can be turned against itself, since Washington noted that in monarchies, one could justify favoring or at least indulging the spirit of party among patriots, in order “to keep alive the spirit of liberty.” One of the arguments in favor of political parties in monarchies is that it is better for partisan intrigues and infighting to be dragged out of the monarch’s court (in this case, the president’s cabinet) and to be made public and accountable. That is how the Republicans read the situation, and from 1792 onwards, having failed to get Washington on their side, they felt their way towards more open and scathing criticism of him. In July 1796, when he was about to leave office, Washington could not stop himself from complaining (to Jefferson, who was then in temporary retirement, and still corresponding with Washington) about “the grossest and most insidious misrepresentations” of his administration, in one-sided, exaggerated and indecent terms “as could scarcely be applied to a Nero; a notorious defaulter; or even to a common pickpocket.”

From 1794 onwards, Republicans were becoming more and more conscious that they would have to mount a partisan campaign for the presidency, their control of the House of Representatives having proved insufficient to outweigh the presidency’s influence on public policy. Discrediting and eventually replacing Washington became their goal, although they knew that this would always be a delicate business. Jefferson then helped other Republicans build up a picture of Washington as a somewhat senile puppet being controlled by Hamilton and others. Of course, Jefferson himself never criticized Washington in public—except inadvertently when yet another of his private letters found its way into the press, and (in March 1797) there was (now Vice President) Jefferson to be seen by one and all, declaiming against “the apostates” to the republican cause, “men who were Samsons in the field and Solomons in the council, who have had their heads shorn by the harlot of England.” (After that, no further communication ever took place between Jefferson and Washington!) Washington’s death in 1799 was mourned, but remembering Washington then did not serve to revive Federalists’ political fortunes.

The presidency was the obvious top prize for American partisans to contend for, but seeing or admitting this was difficult while Washington’s prestige remained great. If Republicans had been able to set their sights on the presidency in 1792, the partisan warfare of the 1790s might have been over much more quickly. There were some purely historical reasons for the lack of electoral competition for the presidency: there had been no such prize either in colonial politics or under the confederacy (1776-1787), so American electoral politics had always naturally focused on legislators rather than executives. But the main reason that it took so long for the presidency to become the focus of electoral attention was Washington. When his retirement made the office available to others, the fact that it is a unitary executive office became a force encouraging a two-party competition. (A plural executive could have been more likely to encourage a multi-party system.) Under Washington, the presidency worked against party government; after Washington, it tended to work in its favor. So his Farewell Address, for all its advice against partisanship, was the signal for partisan competition for the presidency to begin.

Hamilton’s Innocence and Guilt

Alexander Hamilton got himself involved in a sex scandal when an adulterous affair of his became known privately to a few politicians in December 1792. In 1797 this scandal was made known to everyone by James Callender, a journalist who had no scruples about publishing it. Ironically, this was the same journalist who in 1802 would print and thereby spread the (never proven) rumor that Jefferson had had a sexual liaison with one of his slaves. The emergence of party politics was the reason why both of these scandals were widely publicized: in 1797 Jefferson had encouraged the journalist to reveal Hamilton’s affair, and in 1802 the journalist—as Abigail Adams (John’s wife) piquantly wrote to Jefferson—”bit the hand that nourished him” when Jefferson refused to go on supporting him. The journalist had spent time in Richmond jail (where he had heard the rumor about Jefferson’s liaison) after being convicted under the Federalists’ sedition act of 1798. He was pardoned by President Jefferson in 1801 (along with all others convicted under that act). In 1803 he died in circumstances unknown; his body was found floating in shallow water of the James River in Richmond.

Although Hamilton admitted to his adultery, he was not guilty of financial misdeeds, either in his duties as Secretary of the Treasury (which he performed faultlessly), or (as far as is known) in any other way. Therefore, Republicans could never prove their various suspicions and charges about Hamilton’s financial and administrative misconduct. Congressmen investigated him as thoroughly as they could, and he always replied with an impressive amount and quality of information to every question that they raised. In fact, the reason that Hamilton furnished details of his sexual affair (both privately in 1792 and publicly in 1797) was that this was necessary in order entirely to clear himself of the charge that he was involved in any financial or official impropriety.

However, Republicans never stopped thinking that Hamilton must be guilty of some kind of corruption. But what they really had in mind was their thought that his whole system of policy was corrupting America, and in one sense they were undeniably right about this. Here Hamilton was guilty. He did not buy support in congress, and did not fiddle the books at the Treasury, so he was not guilty of that kind of corruption. But his program was encouraging the American people to become corrupt, if by that was meant two things: (1) being susceptible to the temptation of the fast buck, rather than always being patiently industrious; and (2) being content with a subordinate or at best an interdependent commercial relationship with Britain. In fact, in most Republicans’ eyes these forms of “corruption” were two sides of the same coin, and the coin was the British model of economics and politics. In spirit and in form this was a non-republican model. Hamilton’s program introduced the spirit, and eventually, they reasoned, the form would follow. Madison tied it all together very nicely in congress in January 1794 (in a speech also published as a pamphlet), when explaining (again) his opposition to continued over dependence on trade with Britain. This not only gave British money too much influence on American commerce and therefore on American “public councils.” It was also very likely to affect “our taste, our manners, and our form of government itself.” What was the point of the American Revolution if America was now going to slip back into the British orbit, and slide back into low, unrepublican ideas and practices?

James Callender, the journalist who was to publicize the Hamilton and Jefferson sex scandals, began his career in American partisan rhetoric by republishing in Philadelphia in 1794 (from the London and Edinburgh edition) a pamphlet dissecting and displaying the sleaze of the British Empire. Callender purported to show how the British system of taxation, war and conquest inevitably resulted in destruction, misery, and an endless series of massacres and ruinous taxes. Callender’s preface cited Jefferson’s comments that the pamphlet showed “the most astonishing concentration of abuses, that he had ever heard of any government.” Against such ideologically-determined anti-British sentiments, patronized by the American Secretary of State, it was difficult for the cool Hamiltonian Federalist response to have any effect. It was useless for Hamiltonians like William Loughton Smith (congressman from South Carolina) to point out (like Madison, in a pamphlet as well as on the floor of the House) that Madison’s and Jefferson’s repeated proposals for commercial retaliation against British trade rules would simply have had the effect of making Americans pay for more expensive imports from other countries. This argument did not meet the rooted Republican objection to continuing such a high volume of commerce with a country that embodied everything worst about unrepublican government and economics. In their view, continuing that commerce could only continue to infect America with anti-republican views and practices.

In the minds of some leading Republicans, Hamilton’s guilt was compounded by his personal background. Hamilton had been born and brought up in the West Indies, and in spite of his brilliant and courageous army service in the Revolution, his lowly origins and non-native status as well as his attachment to British ideas of political economy made it possible for Republicans to raise doubts about his American and republican loyalties. This personal dimension of the Republican distrust and even hatred of Hamilton is visible in Jefferson’s malicious remark in his response to Washington’s appeal to the members of his cabinet to pull together: Hamilton, he wrote, is “a man whose history, from the moment at which history can stoop to notice him, is a tissue of machinations against the liberty of the country which has not only received and given him bread, but heaped its honors on his head.”

How did the spirit of the Hamiltonian project register in the minds of various groups of American voters in the 1790s? Although we do not have exit poll results to show us the sociological patterns of the support for the two parties, we can discern a close though interestingly indirect relationship between economic interests and party principles, policies and rhetoric.

Economic Reality and Political Rhetoric

Hamilton had a very sensible response to the Republican accusation (cataloged for him by Washington) that speculation in government debt and bank stock “nourishes in our citizens vice and idleness, instead of industry and morality.” To Washington, Hamilton admitted that this accusation, “within certain limits, is true,” but insisted that “most theorists and all practical men” agree, and observation tells us, that this stock acts as investment capital, so its general effect is to promote not the gambling spirit occasionally displayed by a few, but an industrious spirit, encouraged by the rising level and diversity of employment that the new capital makes possible.

Hamilton’s defense against Republican accusations was theoretically and practically sound, but had an important rhetorical weakness. There was indeed a gradual, solid growth in the American economy in the 1790s. But this economic fact was accompanied by a remarkably high level of anxiety, which easily translated into Republican fears about the moral perils of economic development. So while many Americans obviously found the Hamiltonian project attractive, they also found it repulsive. They could not help fearing that Hamilton was the serpent in their republican Eden, slyly tempting them with Machiavellian ploys to indulge acquisitive passions that they felt they should be suppressing.

This anxiety did not lead Republican supporters to a wholesale rejection of the Hamiltonian temptation. It did not lead them to a romantic retreat to an agrarian utopia in which there were no calculations of profit and loss. Americans—including Republicans—were acquisitive and industrious, and sometimes even not averse to the odd speculative gamble. But if they ate the fruit of the tree of economic knowledge, they denied having done so, by supporting and engaging in a political rhetoric that denied that they were adopting the theories and practices inherited from unrepublican regimes, particularly from their “mother country.”

This was not completely neurotic behavior, and it can be described in terms that are more sympathetic and generous to Republicans, and more critical of Federalists. It was not simply that Americans wanted what the Federalist project was offering (economic development) but were unwilling to admit this. There is some truth in that picture, but it was also true that Federalists, for all that they championed the principle of equality of opportunity, were slow and indirect in making economic opportunities widely available. So while the Republicans failed to preach what they practiced, the Federalists failed to practice what they preached. We have seen that Hamilton’s policies allowed temporary monopolies for the sake of priming economic growth. That was justifiable, though sometimes politically difficult to justify, especially when the trickling down of employment and wealth was slow. However, there was a less justifiable social and economic exclusivity among Federalists, which made those outside the circle feel they could never get in, and therefore stirred them to set up their own circles—which included their own enterprises, even their own banks. Historians who have studied the economic interests of Federalist and Republican voters during the 1790s have shown that the pattern was for Federalists to have greater support in longer-established, less upwardly-mobile groups and areas. Republicans—sometimes surprisingly to some of the richer and more established of the party leaders—got support not just from farmers but from “new men” of all occupations, men taking advantage of economic growth to better their condition. Federalist observations of the socio-economic basis of the partisan division back up this portrait, although naturally the Federalist account puts down the Republicans by calling them not enterprising “new men” but (in the words of a Massachusetts newspaper in 1800) “desperate, embarrassed, unprincipled, disorderly, ambitious, disaffected, morose men,” in contrast to the Federalist ranks, filled with “quiet, honest, peaceable, orderly, unambitious citizens.”

If anything, then, Republican supporters wanted what the Federalist project was offering but wanted it faster and less exclusively. But Republican rhetoric did not say that. Although (perhaps because) Republicans wanted it faster, they did not want to admit that they wanted it at all. Republicans did not justify their challenge to Federalists on the grounds of Federalists’ failure to practice what they preached on the theme of equal opportunity. That would have risked agreeing with the Federalist principle that equality of opportunity among the people had to be supervised and regulated by a central government capable of channelling and moderating as well as empowering the people’s economic ambitions. Instead, Republican rhetoric insisted that central government policies, not the people’s ambitions and vices, were the source of any economic troubles, such as the occasional speculative bubble or economic panic. Albert Gallatin (later President Jefferson’s Secretary of the Treasury, and a very astute financier) claimed that Hamilton’s funding and bank systems, “with the speculations that have grown out of them, have substituted an avarice for wealth, for the glory and love of country.” James Sullivan (formerly a Federalist, and later the Republican Governor of Massachusetts) took issue with Hamilton’s systems because they introduced “a spirit of envy” into the minds of Americans who “had been quite content with their situation”; Hamilton’s systems were a “Machiavellian policy—to render vice, as vice, subservient to the purposes of virtue.” Sullivan contended that this was an unreliable and unnecessary policy, which spread corruption down from the government to the people: “natural genuine virtue exceeds all the artificial substitutes, which a corrupted and abandoned set of politicians can produce.” Under Federalism, it was not wealth but corruption that trickled down.

Republican rhetoric also insisted that these corrupting government policies could only be mended by the Republican party’s acceding to power and committing the federal government to less control over the economy. John Smith, in a Fourth of July oration at Suffield, Connecticut in 1799, made this Republican point: the need for energy in government is in inverse proportion “to the vices which it creates.” If government did less harm to the people’s character, it would thereby be less obliged to do good in order to compensate for that harm. It would not have so closely to supervise the people’s economic life if it had not first corrupted that life.

This paradoxical relationship between the Republican party’s economic and social interests and its sincere and passionate rhetoric is psychologically similar to American attitudes towards Britain. Here also there was a deep and troubling conflict, between interests and passions. In 1787 (that is, even before France became a republic), Jefferson warned a French visitor to America that he would notice a conflict between American habits and affections, the habits bound up with England (“chained to that country by circumstances, embracing what they loath”), but Americans’ affections all with France. Republican policy was to escape from these circumstances, to cut America loose from dead or dying England, and to redirect Americans’ habits towards their true love, France. In 1799, Fisher Ames (a Massachusetts Federalist) commented on the love-hate relationship between Americans and their mother country. Americans like individual Englishmen, but hate England, he said, precisely because America and England are so alike: nations, like individuals, often prefer their passions (France) to their interests (England).

Republican rhetoric thus took a very roundabout way to make a point, and it was a way that sometimes brought more heat than light to the subject. But this rhetoric did not lack a reasonable and justifiable point—namely, that Federalists were too socially and economically exclusive, and that they underrated the morality and political competence of the American people.

Furthermore, if Republicans had made that point in a less indirect and less heated manner, they would have been far less able to create a political persuasion with the breadth and depth of appeal that they needed to have in order to create American party government. So the more general lesson here is that principled political parties, in order to be successful in rallying popular support, must mobilize righteous indignation and pride as well as coolly calculated coalitions of interests. Hamilton himself reached such a conclusion about the rhetorical weakness of his project, when, reflecting on the Federalist downfall, he wrote, in 1802: “Men are rather reasoning than reasonable animals, for the most part governed by the impulse of passion.”