From Bullets to Ballots: The Election of 1800 - Ch. 8

Suppression, Protest and the Revolution of 1800

While the Republicans at the end of the 1790s were becoming wiser about international politics, the Federalists were becoming less wise about domestic politics. Most of them did not want war with France, but many of them did want to use the foreign policy crisis to clamp down on domestic opposition to their administration of the federal government. The Federalist party’s determination to triumph over domestic political opposition was so counterproductive that it can be seen as one of the main reasons for the Republican party’s triumph in the Revolution of 1800.

In the spring of 1798, at the height of the outrage against the French treatment of American diplomats and commerce, Federalist strength in Congress increased even before any elections; many Republican congressmen simply gave up and went home. Federalists took advantage of their congressional strength to embark on a program of political suppression. In June and July they passed (by very slim margins) a naturalization act that extended from five to fourteen years the period of required residence before applying for citizenship, an alien act (expiring in two years) giving the president the power to deport nonnaturalized aliens that he deemed dangerous, and a sedition act (expiring in March 1801, i.e. at the end of the current presidential term) that made it a criminal offense, punishable by a fine or up to two years in prison, to publish false and scandalous writings against the federal government or to excite unlawful combinations to oppose any law or act of the government. These measures were designed to be used against Republican party publicists and supporters, particularly Irish and French immigrants (some of whom were also editors of Republican newspapers). The sedition act was never invoked against hawkish Federalist critics of Adams.

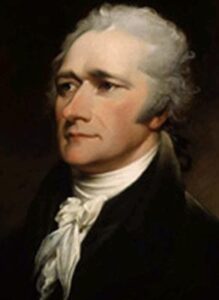

Hamilton was very wary of the alien and sedition acts. Adams had not requested such measures (although he did not veto them). Federalists in congress also exceeded President Adams’ response to the French crisis in their spending (and taxing) legislation, to create a large new army. (Adams preferred to focus the country’s defense efforts on the navy.) This new army, it was eventually agreed, was to be commanded by ex-President Washington, which Adams favored, but, at Washington’s insistence, and to Adams’ dismay, Hamilton was appointed second in command.

These arrangements, premised on the dangers of a French invasion which was never really a threat, and became even less so after Nelson’s destruction of the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile in the summer of 1798, could have been designed by a clever Republican dirty tricks operative to ensure that the Federalists would unite American public opinion not in their favor but against them! This was certainly the case once Adams undercut Hamilton’s military career—and made Washington’s reappearance in national politics a brief episode—by nominating the new peace mission to France in February 1799. But the Federalists’ legislative program of 1798 had already provoked the traditional American hostility to standing armies in peace time (a well-known anti-republican device), as well as vigorous protests about the alien and sedition acts. This program also had the effect, which Republican leaders had been expecting for some years, of alerting Americans to the increasing tax burden that the federal government was placing on them.

The alien and sedition acts did not represent the Federalists’ finest hour. In their defense, it could be argued that these acts were considered as wartime measures, and that they were not all that extreme in the context of their day. Britain had passed and enforced much more extreme laws along these lines. For example, over there Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man was judged to be seditious, and anyone printing or selling it was prosecuted. Also, the American laws of 1798 made truth a defense against a sedition prosecution; this was a major departure from English law. However, there were also great and relevant differences in the circumstances of Britain and America. In Britain, the danger from revolutionary France was more immediate, and the radical critics of the government were much thinner on the ground. American public opinion was much more divided, even at the height of the war fever of 1798. The Federalists’ laws were therefore preposterous attempts to generate the kind of unified public opinion that such laws presupposed for their legitimacy and effectiveness.

Neither the alien nor the sedition acts were very effective, at least not in the ways intended. President Adams never exercised the deportation power (though some aliens did leave of their own accord). One of the main effects of the alien laws (like similar legislation in later times in American history) was simply to encourage large numbers of naturalizations (including that of the journalist James Callender, who had left Britain to escape punishment for sedition, but was then convicted under the American sedition law). New applications for citizenship—and for voting rights—were encouraged by Republican partisans, and these new citizens helped swell the numbers of Republican voters in 1800. The Federalists’ clumsy relations with non-English ethnic groups, including their armed suppression of a tax revolt in Pennsylvania, turned even solid, Federalist-sympathizing German-Americans into good Republicans.

The sedition law (which had been opposed by some eminent Federalists, such as John Marshall, who joined House Republicans in a nearly-successful effort to repeal it in January 1800) resulted in 25 arrests, 14 prosecutions, and 10 convictions. But even the sedition act, which compared to the alien laws was a more serious (albeit temporary) blow to the Republican party (and to any future party that wanted to use the full range of the freedom of the press), had its immediately and sometimes hilariously counterproductive side. Prosecution under the sedition act transformed Matthew Lyon and Jedidiah Peck into heroes of the Republican cause, whose political futures were greatly enhanced by their martyrdoms. (Congressman Lyon of Pennsylvania had been known earlier for his brawling with a Federalist on the floor of the House of Representatives. Peck was a Federalist legislator in the New York state Assembly, whose crime was to start criticizing the alien and sedition acts soon after taking up his Assembly seat.) A few prosecutions of Republicans in New England (under state as well as federal sedition laws) resulted in severe punishments, but also became campaign issues for the Republican party in 1800. One prosecution in New Jersey based on the defendant’s unflattering reference to President Adams’ posterior resulted in a jury verdict of not guilty on the ground that the truth of a statement was a good defense.

In spite of the ineffectiveness and occasional silliness of the alien and sedition laws, they demonstrate the depth and seriousness of the partisan divisions, which made such laws seem like reasonable measures to many of the partisans. In fact both sides used such weapons, not just Federalists. Abigail Adams—whose political judgment was usually good—suggested that prosecutions for seditious libels would help place the Republican “traitors” in a category like “Tories in our Revolution,” deserving no respect and no part in public life. The man she was then calling “Scoundrel Jefferson” darkly predicted that the federal sedition law was another proof of Federalists’ antirepublican conspiracy; this step would be followed by a move to make the presidency and Senate into offices for life, and then by even more extreme measures of the monocratic plot. Yet Jefferson also spoke of his partisan enemies as traitors and heretics, and after he became president, he himself encouraged the prosecution of Federalist editors (“tory presses,” he privately called them) under state sedition laws. In his Second Inaugural Address (1805), he noted that in the American press controversies during his first administration, “truth and reason have maintained their ground against false opinions in league with false facts,” and he suggested that therefore “the censorship of public opinion” was perhaps better than legal actions against unrepentant propagators of “false reasonings and opinions”; but he did not rule out the possibility of having to depend on “the salutary coercions of the law.” In 1799, state libel laws were used by a Republican, Benjamin Rush, in the Republican-controlled courts in Pennsylvania, to ruin and to force into retirement a Federalist-sympathizing editor (and English citizen), William Cobbett.

The main point remains, however, that as a partisan tactic, the Federalists’ attempts to legislate greater unanimity in their favor was completely counterproductive. It provided the Republicans with an appealing issue around which to build their renewed electoral efforts. In retrospect, we can see that the Federalist party was acting so self-destructively that the Republicans actually had to do very little in order to gain their Revolution of 1800. In the autumn of 1800, the bitter enmity between John Adams and Alexander Hamilton, and the related divisions within the Federalist party, were made matters of public record by Hamilton’s circulation of a pamphlet diatribe against Adams’ Public Conduct and Character. By then, large numbers of voters had already turned away from the Federalists.

The Republicans’ Response

The retrospective view, notoriously, is never available at the time. Republicans, not knowing the end of the story, and knowing only too well the proven capacity of the Federalists to avoid electoral punishment for their anti-republican actions, took the new aggressiveness of the Federalists in 1798 very seriously. They maintained their bedrock confidence, but their first protests against this aggression were a little desperate and at first not completely effective. In November and December 1798, the legislatures of Kentucky and Virginia passed resolutions protesting against the unconstitutionality of the alien and sedition acts, using strict constructionist arguments similar to those that Madison and Jefferson had first used against the national bank in 1791. They also repeated the now familiar Republican accusation that the federal government’s policies had the effect of consolidating government power, with the inevitable result of transforming the republic into a monarchy. Jefferson and Madison had drafted these resolutions in great secrecy. Madison had retired from congress in 1797, and although Jefferson was vice president, unchallenged Federalist control of all branches of the federal government left the state legislatures as the highest government bodies where majorities could now be found in support of the Republican cause. But using this only available governmental channel might have made the party seem to be only a local, southern phenomenon, if Madison’s and Jefferson’s roles had not been cloaked in secrecy.

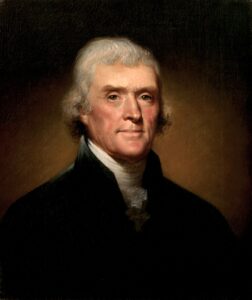

At the beginning of June 1798, just before congress passed the alien and sedition acts, Jefferson had written a very revealing letter to John Taylor (who would actually propose the Virginia resolutions drafted by Madison). When writing this letter in Philadelphia, Jefferson, presiding over the Senate, was well aware of the collapse of the Republicans in congress after the revelation two months previously of the French demands for apologies, bribes and loans. So although the alien and sedition acts were not yet in the statute books, Jefferson was aware of the war fever against France and the public temper that would lead Federalists to pass these acts. Nevertheless, Jefferson expressed optimism about the Republican party’s prospects. He assured Taylor that although the Republican party was for the moment out of power, time and events were still on their side. Therefore, any talk of breaking up the union in order to get rid of the Federalist ascendancy, which was most solidly entrenched in New England, was unwise. He reminded Taylor that there were good republicans “through every part of the union” who knew that it was “the cunning of Hamilton” in playing off “the irresistible influence and popularity of General Washington” that had “turned the government over to antirepublican hands, or turned the republicans chosen by the people into anti-republicans.” It was only the “very untoward events” of 1797-1798 (the crisis with France), “improved with great artifice,” that had made the American public not yet prepared to throw out the anti-republicans. Never mind: “A little patience, and we shall see the reign of witches pass over, their spells dissolve, and the people recovering their true sight, restoring their government to its true principles.”

The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions suggested that there was reason for less confidence than Jefferson had voiced a few months before in this letter to Taylor. The Kentucky Resolutions (drafted by Jefferson) emphasize that it is wrong for the people to place too much confidence in elected officials: “In questions of power let no more be heard of confidence in man, but bind him down from mischief by the chains of the Constitution.” Confronted with palpably unjust and unconstitutional acts by their duly elected federal government, it would clearly be “a dangerous delusion were a confidence in the men of our choice to silence our fears for the safety of our rights.” Not confidence but “jealousy” is the basis of constitutional limits that “bind down those whom we are obliged to trust with power.” Only such a spirit of jealousy can be relied upon to arrest such unjust and unconstitutional acts “on the threshold.” If they were not so arrested, they could well “drive these states into revolution and blood.” For the sake of the future of the federal government as well as for the security of our rights, we must no longer patiently rest on our oars, we must immediately arrest misdeeds by those we have elected to the federal government.

But what follows from these resolutions? If elected officials—”the men of our choice”—do not deserve our confidence, can elections deserve our confidence? In 1832, the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions were to be used (misused, as Madison, still alive and thinking, ably demonstrated at the time) to justify nullification of federal laws and secession by any state that judged itself and its citizens to be in danger from unjust and unconstitutional acts of the federal government. And it is true that these Resolutions were addressed to the other states (who, however, failed to respond positively). Is unilateral action by individual states, or even by individual citizens, not justified when tyranny threatens rights, even if such action might involve violence, and even if these citizens have freely elected those who are now showing themselves to be tyrants?

The answer is yes, of course it is, but such unilateral action, if it goes beyond protesting to violent resistance, will be an exercise of the natural right of revolution, rather than of a more strictly political or constitutional right. This is the familiar reasoning of the Declaration of Independence, although there the tyrannical governors had not been freely elected. But the question from 1798 to 1801 was whether “revolution and blood” were the necessary outcome of the conflicts between the Federalist and Republican parties, or whether, now that the governments in question were fully based on free elections, it was possible to resolve such conflicts of principle by electoral ballots rather than by revolutionary bullets. In his letter to Taylor, Jefferson was expressing confidence (as he had done ever since 1792) that the electoral process would eventually resolve conflict between Federalists and Republicans, in which “principles are the stake,” in the right way, with the Republicans on top. Had the new Federalist aggressions of 1798 changed that? Ominously, the Federalists were now attacking (as Madison said in the Virginia Resolutions) “the right of freely examining public characters and measures, and of free communication among the people thereon, which has ever been justly deemed the only effectual guardian of every other right.” The Federalists’ violation of the rights of freedom of speech, press, assembly and petition (in spite of their being stated in the first amendment) was the most alarming thing, and if allowed to stand would interfere with free elections, in which the Republicans had placed great hope.

Although the arguments of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions may suggest that the Federalist aggressions of 1798 had indeed radically changed the situation, it is clear that Madison and Jefferson, while emphasizing that confidence in the current elected government was not warranted, maintained their confidence in the electoral system. For they intended these Resolutions to serve as part of the ongoing and nationwide Republican effort to defeat the Federalists in elections—with ballots, not bullets. However, it was reasonable to engage in some revolution rattling as part of this effort, for several reasons. The natural right of revolution is based on the natural purposes of government—the people’s safety and happiness—which even freely elected governments need to be reminded of, to keep their minds on their jobs. Reminding them of the right of revolution also makes them realize that even if they did ever manage to thwart the wishes of the majority by suppressing political speech and organization or by rigging or suspending elections, the majority would not be without an alternative way of putting things right. By counting votes, free elections replace (more precisely, supplement) but also approximate violent revolutionary conflict, in which numbers also matter. Voters sitting in judgment on elected governments also benefit from being reminded of the right of revolution and the purposes of government; this encourages them to use elections to judge the government rather than mechanically to defer to it, and it recalls the criteria for their judging: the people’s safety and happiness. By maintaining voters’ alertness and judgment, parties can help ensure that the need for revolution does not arise.

The Kentucky Resolutions themselves conclude not with a call to arms, but by calling upon other states to unite with Kentucky in requesting the repeal of the alien and sedition acts at the next session of congress. And in 1800 Madison made clear in the Virginia report on other states’ responses to the Virginia Resolutions that these Resolutions, primarily concerned with the credible threat that the United States was being transformed from “a republican system into a monarchy,” were “expressions of opinion” intended only to excite others to reflect on their own opinions, with a view to bringing about changes in “the legislative expression of the general will.” Recourse to bullets was not (and never can be entirely) ruled out, but in 1798 reliance on ballots was still a viable option. Perhaps resolutions of state legislatures were a misleading medium to use in a nationwide political campaign, but with Republicans having to keep a low profile in congress, the postal system currently an untrustworthy method of communication, and Republican presses under legal as well as physical assaults, the use of state resolutions was justifiable.

At this stage, it was the Federalists rather than the Republicans who—or at least some of whom—felt they might need to depend on bullets rather than ballots. The Republican leaders carefully discouraged any violence or law breaking. In February 1799, Jefferson advised and predicted: “keep away all show of force, and [“the American people”] will bear down the evil propensities of the government by the constitutional means of petition and election.” However, the new army, serving little purpose against foreign threats, could be a tempting means of suppressing domestic enemies. A few Federalists speculated about this possibility. Among them was Hamilton (now General Hamilton). In February 1799, when Federalist newspapers were circulating (false) rumors that Virginia was backing up its stand in its Resolutions by arming, Hamilton wrote (in a private letter) that the army might be useful to “put Virginia to the test of resistance.” It is difficult to imagine Washington leading the army against Virginia. And in fact, when the army was used domestically, in the spring of 1799 (before it was finally disbanded in 1800), it was used not against Republicans, but to hunt down (too late, and probably quite unnecessarily) what it could find of a tax rebellion in southeastern Pennsylvania—thereby converting counties full of Federalist supporters into life-long Republican supporters. But the speculation of Hamilton and the others about the use of force did reveal the Federalists’ longing for the authority and the popular legitimacy that they no longer seemed to possess the good means to inspire, and did show that the peaceful resolution of the partisan warfare was not necessarily as inevitable as the Republicans were hoping.

The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions were reprinted in the press, and very quickly became topics of public discussion. By January 1799, their effects were combined with those of petitions signed by thousands of citizens, coming into congress from every part of the country, protesting against the Federalist initiatives of 1798, not only the alien and sedition acts but also the peacetime “standing army” and the taxes needed to support it.

However, many of the elections of 1798-1799 occurred while the war fever and patriotic enthusiasms were running high, and the Federalist majority in congress remained intact. Federalists did particularly well in Virginia and the Carolinas, where unionist reaction to the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions was strong. But Republican electoral support strengthened in western Virginia, as well as in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. From the spring of 1799 forwards, while self-destructive Federalist policies and infighting continued, Republican confidence, organization, and electoral victories grew steadily, just as the always sanguine Jefferson even at the lowest point of Republican morale in 1798 had predicted they would. By August 1800, Fisher Ames foresaw the coming Federalist debacle: “The question is not, I fear, how we shall fight, but how we and all federalists shall fall.” But the partisan war was not yet over.

The Electoral Revolution

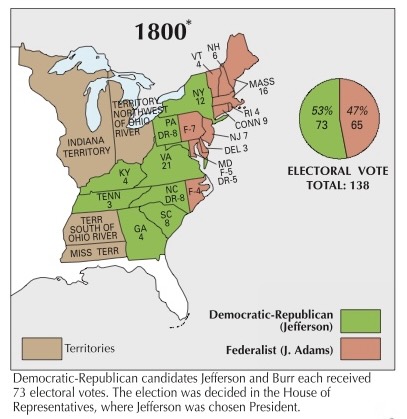

When the congressional elections of 1800-1801 were completed, the Republicans could count on a majority of 65 to 41 in the House—an even bigger margin than the Federalists currently held over them. This majority included several Republican members from the northeastern stronghold of Federalism. The Republicans also won their first majority (of five) in the Senate. Their victory was not only comprehensive, it was also durable. Federalists never regained a majority in either house of congress. Nor did they ever again come close to electing a Federalist president.

However, the last Federalist-controlled House did have the interesting task of deciding which Republican would become president. The electoral college in December 1800 gave 73 votes to both Jefferson and Burr, 65 to Adams, and 64 to Pinckney. In contrast to all three previous presidential elections, no college votes were cast for anyone but these four agreed-upon party candidates, apart from one Federalist vote (by a Rhode Island elector, for John Jay) that went to ensure that Adams came ahead of Pinckney. The Republican electors—perhaps because they were so struck by the sight of the Federalist party’s well-publicized internal bickering—did not arrange for even one such wasted vote, so their two candidates got the same number of votes. The electoral college system, before the twelfth amendment (1804) separated presidential and vice presidential voting, was not designed to cope with such total party solidarity. The failure of the electoral college to choose a president meant that the choice between Jefferson and Burr had to be decided by the House of Representatives (with each state delegation having one vote) as soon as congress officially received the electoral votes in February 1801, so a president could be elected before inauguration day, set for the fourth of March 1801.

When Federalists contemplated their task of deciding between Jefferson and Burr, it seemed to hold an opportunity for them to snatch victory from defeat. Even if they had been defeated in the election, they believed as strongly as the Republicans that only their party had deserved to win. They thought that the electorate had been grossly misled by Republican propaganda, and they believed that Republican control of the presidency as well as congress would be a catastrophe for the country. Were they not justified, therefore, in seeing if they could at least use their power of breaking the tie to extract from Jefferson a promise that he would not undo essential elements of the Federalists’ accomplishments? Or perhaps there were even more promising possibilities. Could Burr, a man known to be much more flexible in his views than Jefferson, not be made president? Then, in his gratitude to the Federalist king makers, he might be depended upon to pursue their policies rather than the Republicans’. Or, more radically: could this first failure of the electoral college not be regarded as a justification to declare the presidential election invalid? Between the electoral college result in December 1800 and the House convening to make its choice during the second week in February 1801, some Federalists considered refusing to choose between Jefferson and Burr, so they could name an acting president and organize another election.

So perhaps Jefferson’s hope to take the presidency could still be defeated, or at least his presidency could be defanged by extracting policy guarantees from him (or if necessary from Burr) before he was permitted to take office. If the Federalists could achieve either of these things, then Jefferson’s belief that Americans were in the process of discovering a new, non-violent kind of revolution through elections, as a supplement to the older, violent kind of revolution, would be mistaken.

In the whole history of mankind there was no precedent for such a peaceful transfer of power from one set of politicians and principles to another, based on free elections. Why should the Federalists allow such a precedent to be set now?

Arguably, with the most favorable Federalist spin, even the election results could be seen as not unambiguous in support of the Republicans. True, Republicans had won a majority in congress, but they had had slight majorities in the House of Representatives from 1793 through 1797 as well, so perhaps that was not the decisive thing, and the presidential contest was what mattered. Here was room for Federalist hopes, for the future as well as for the present. In the electoral college voting, apart from in New York, the Federalists actually did better than they had in 1796. In 1796, New York’s presidential electors had voted for Adams. The switch of New York’s twelve electoral votes away from Adams in 1800 cost him the election. And that switch had occurred only because of Aaron Burr’s energetic organization between 1796 and 1800 of an urban political machine in New York City. Burr was not a principled republican politician but one whom Hamilton called (among other things) an “embryonic Caesar.” (That is why Hamilton later on would be horrified at the idea of the House Federalists making Burr president.)

To Hamilton and other Federalists in New York, the success of the Republicans in the contest in New York City had been so shocking, and its probable consequences in the upcoming presidential election so evil, that they tried (without success) to persuade the Governor (John Jay) to call a special session of the legislature to change the state’s presidential election procedures, to select electors by popular vote in each district rather than by the state legislature’s vote. Burr’s success in New York City meant that the next legislature would have a Republican majority that would (as they did) give all of the state’s twelve votes to Jefferson (and Burr). Election by district would mean that the state’s twelve votes would end up being divided between Adams and Jefferson. (The Hamiltonians hoped for a majority of the twelve for Adams, but as it happened even a shift of five New York votes to the Federalist column would have been enough to put Adams into first place in the national results.) Hamilton wrote to Jay in justification of this change that any “scruples of delicacy and propriety ought to yield to the extraordinary nature of the crisis.” Such adjustments of election procedures with a view to influencing their results were not uncommon, but it was not usual for them to take place after the agreed procedures were underway. Nevertheless, Hamilton was sure that the action was justifiable: it was, he pointed out, legal and constitutional, and it was necessary, he wrote, in order to prevent Jefferson, “a fanatic in politics,” from taking over “the helm of the state.”

The Federalists sincerely believed that the country had nothing to gain from a peaceful transfer of power to Jefferson, and very much to lose. The system of public credit and the neutral foreign policy established with such pains during the Washington and Adams administrations were sure to be undermined by the Republicans in power. And the wild, Jacobinical ideological tendencies that the Republicans had displayed since the French Revolution suggested that all of the achievements of the American Revolution and the constitution making of the 1770s and 1780s would be reversed by them. Even at its best, a Jefferson administration would turn back the clock to the days before the Constitution had energized the federal government and had thereby put a stop to many of the short-sighted and unjust actions of the state governments in the 1780s. At its worst, Jefferson and the Republicans would replicate in the American republic the mobocracy of the French republic and the military dictatorship that grew out of it. The hopes of mankind for all the benefits of liberty rested on America. How could the Federalist party just walk away from the battle?

Federalists did not pursue their idea of declaring the presidential election invalid. If they had, or even if they had succeeded in taking the perfectly constitutional step of choosing Burr over Jefferson, there would probably have been armed backing for measures to reverse their action. Republicans regarded both of these contemplated Federalist actions as “usurpation.” At the very least (as Jefferson would write soon after his inauguration), Republican congressmen would have assembled a constitutional convention, which would have amended the Constitution in order to ensure that the “virtual” president and vice president (i.e. himself and Burr, respectively) would become the actual president and vice president. The Virginia and Pennsylvania militias were put on alert; with the government now installed in Washington, DC, these forces would have been well placed to protect such a convention and to detain its opponents if necessary.

The partisan divisions in the state delegations in the House of Representatives were such that it took six days and thirty-six ballots for the House to choose Jefferson as president (which automatically made the remaining candidate with the most votes—Aaron Burr—vice president). The man who finally changed his mind to make this possible was James Bayard, a young lawyer and the (sole) Federalist representative from Delaware (who therefore controlled single-handedly that state’s vote in this balloting). Hamilton had written to him (and to many other Federalist congressmen) about the imperative of choosing Jefferson over Burr (even though Jefferson was “a contemptible hypocrite”). But Hamilton’s advice was not being followed by Federalists in Washington. It may have had some influence on Bayard’s decision, but even after receiving it Bayard had at first been going along with other Federalists’ efforts to elevate Burr over Jefferson. But voting by state delegations meant that Federalists did not have enough votes to choose Burr, though they did have enough to prevent Jefferson from getting the required majority of nine out of the sixteen states. Why did Bayard change his mind and break the deadlock? Bayard claimed to have received indirect assurances that Jefferson would not remove anyone from office merely on political grounds. But later, in 1805, Bayard explained his decision (which was not to vote for Jefferson—dreadful thought—but to cast a blank ballot) by saying that he was “chiefly influenced by the current of public sentiment, which I thought neither safe nor politic to counteract.”

Bayard’s explanation can stand as a concise summary of the reasons for the Revolution of 1800. Public opinion, along with the possibility of any necessary coercion visible in the background, was the decisive factor, not just in Bayard’s decision allowing Jefferson to be elected president in an orderly manner, but in the whole electoral revolution that had been in the making since 1792. In eight years, Federalists had lost the battle for public opinion. They were not easily reconciled to accepting that loss, but reluctantly and gradually they saw they had no alternative, unless it were to consist in a forlorn attempt to organize a secession of the states in which they felt they could muster a majority.