Meet Our Teachers

Anne Hester

Anne Hester, a 2017 graduate of the Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) program, teaches two advanced versions of US history at East Lee County High School near Fort Myers, Florida. One is an honors course that begins in 1850 and continues through the present day. The other is a collegiate level Cambridge Advanced International Certificate of Education (AICE) course; it takes a close look at US history between 1820 and 1941. Hester makes a speech on the first day of each school year: “Everybody got your schedules? Find the person listed as your guidance counselor. We are going to talk about things in this class that will make you uncomfortable or even angry. If you are easily offended, you are in the wrong class. Go get a schedule change. If you stay here, you’re going to learn stuff you wish you’d never learned.

“But at the end of the year, you’ll be glad you did.”

To date, the speech has not caused a student to drop Hester’s course. It seems rather to pique their interest. Hester’s students are among the school’s most motivated, and discussing the difficult aspects of US history with each other helps them make sense of their own experiences. “We are 61% Hispanic, 21% Black, 15% White, 2% biracial and 1% Asian. On paper, that may not sound very diverse, but we are incredibly diverse. We have Mexicans, Cubans, Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Haitians. We’ve got kids from all over the place, some whose ethnicity combines three or four different groups. The kids understand that we all have opinions. They realize that if we can respect each other’s opinion, even if we disagree, we can still all be heard.”

Centering Reconstruction in the US History Course

Because Florida places the dividing line between middle school and high school study of American history at 1850, Hester can begin her honors course in the decade of intense sectional conflict that led to our Civil War. After studying the Civil War, her students spend time considering the daunting challenge that was Reconstruction in the South—unlike students elsewhere, who usually get a quick summary of Reconstruction at the rushed end of their eighth-grade year. As Hester puts it, “we start the year discussing what led up to the near deconstruction of the United States. And then we jump right into the reconstruction of the United States.” In her AICE course, also, students learn about the promise and failure of Reconstruction by mid-year.

“You can’t understand why Reconstruction failed unless you understand what tore the country apart in the first place. Nor can you understand how that failure affects us even today,” Hester said.

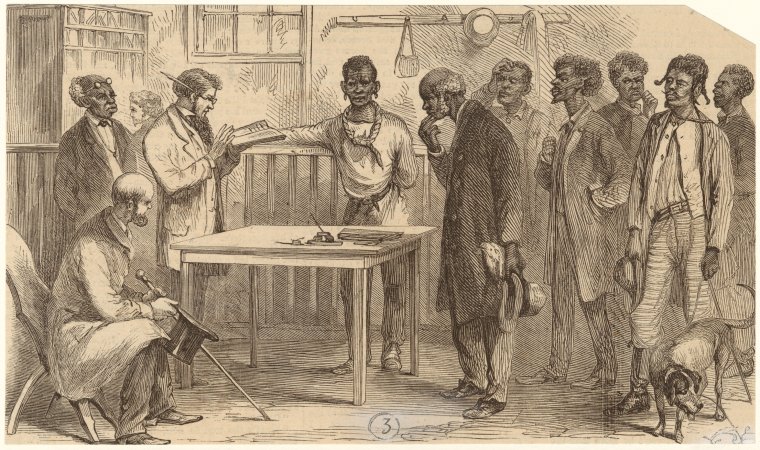

At TAH Seminar, Teachers Discuss Reconstruction’s Failure

Hester and other teachers discussed this critical era in US race relations at a TAH multi-day seminar in Atlanta in April 2023 on “The Failure of Reconstruction and the Rise of Jim Crow.” Professor Brent Aucoin of the College at Southeastern in Wake Forest, NC, facilitated the conversation. He guided teachers through a packet of readings beginning with Lincoln’s plans for Reconstruction, as the Civil War drew to a close, and ending with the Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896.

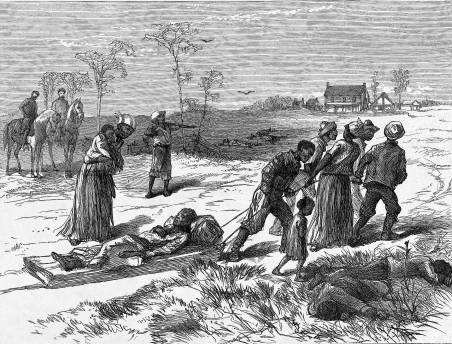

The readings included debates in Congress over what requirements to impose on formerly Confederate states as they were readmitted to the union, as well as Congressional reports on violations of freedmen’s rights in the readmitted states. They traced a waning enthusiasm for guaranteeing black civil rights as a later generation of Congressional leaders prioritized restoring amical relationships between Northerners and Southerners.

They read Supreme Court rulings that undermined the protections for freedmen intended by those who drafted the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. While the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed freedmen the right to vote, the 1876 ruling in Cruikshank effectively overturned an election carried by black votes in Louisiana, by denying the federal government’s right to prosecute those who murdered black defenders of elected officials at Colfax County Courthouse. Although the Fourteenth Amendment invalidated discriminatory state laws such as the “Black Codes,” the Supreme Court ruled in the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873) and Civil Rights Cases (1883) that private owners of public accommodations could discriminate as they chose. And in Plessy, the Court ruled that the segregated train coaches, arguably impermissible under the Fourteenth Amendment because of the interstate commerce clause of the Constitution, could be permitted under the presumption that they offered “separate but equal” accommodations.

Encouraging Civil Discourse

Hester had learned much of this history during her MAHG studies. The seminar did provide her with new primary documents from which she could pull excerpts for her students to read. But she found the opportunity to talk with fellow teachers about the documents worthwhile in itself. “Reconstruction is such a touchy subject. A lot of teachers today are leery of talking about this or other aspects of our racial history. We don’t want to offend; we don’t want to be labeled either insensitive or overly sensitive to racial issues.” Primary documents help to objectify discussions of racial history: they focus our attention away from our own opinions and onto the evidence the documents provide. Hester welcomed the chance to practice such discussions with other professionals. Professor Aucoin helped teachers understand the context in which documents were written and the factors influencing the authors’ perspectives and rhetorical approaches. Most important, he offered a model of careful listening and respectful response. “The weekend seminar fostered the kind of civil discourse that has been the big theme of education for the last two years,” Hester said. Teachers were so eager for such discourse that the chief issue became making sure that everyone had a chance to speak.

Sparking Interest in Primary Documents

Students often need more of a push, and more guidance, to draw meaning from primary documents. In her own classroom, Hester habituates students to a particular analytical process denoted by an acronym. Taking a document APART, she says, entails learning about the document’s Author, the Place and time in which he wrote; his Audience; his Reason for writing; and his overall Theme. Hester introduces each analytical factor somewhat stealthily, beginning with a story about a document’s author.

In a recent honors class, she introduced the “Letter from Birmingham Jail” by telling the story of Martin Luther King’s activism in Birmingham. Her students respect King highly without knowing much about the risks he took. “Miss Hester, they did not arrest Dr. King!” a student said in dismay. “Yes, they did. Many times, in fact.” she replied. “Why did he stand for it?” the student demanded. Hester explained King’s philosophy of leadership: that as a shepherd to his flock, he should walk in front of them as they challenged those enforcing segregation laws. She added that King wrote his letter in response to criticism from religious leaders who said he was provoking civil unrest. “He wrote to tell them, ‘I’m where the flock is; and I’m wondering where the flock are you?’” Now Hester’s students were intrigued, curious to know what King said to his colleagues in ministry. Hester said, “Okay, I’m putting King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail up in Google Classroom. That’s your weekend assignment.”

“Light Bulb” Moments

On Monday, students eagerly discussed what they’d read. “King wasn’t afraid to be punished for his beliefs,” one said. “He wasn’t afraid to be where he needed to be,” another added. “He didn’t fight back! So he was kind of becoming the guy he wanted other people to be—a role model.”

“At any point in the letter, does he advocate violence?” Hester asked. “No,” her students replied, “he’s being all nice and Jesus-y to the other pastors.”

“So, what’s the big picture here? What’s King’s message on civil rights?” Hester asked.

“Be the better person!” her students replied.

“Here I am the proud teacher standing in front of this classroom, watching light bulbs switch on in students’ minds, thinking, ‘Oh, yeah. This is why I teach,’” Hester said. Along with discouraging instances of injustice, American history shows us inspiring acts of leadership to overturn injustice. Hester underscores this point by reminding students of their fortunate inheritance as Americans. “We were given this wonderful gift. We had to fight for our liberty, but many would say we got it relatively easily compared to those in places like France. We didn’t have to kill any kings. The question for each of us is, what are you going do with this gift? How will you make it your own and make sure that it stays available for people long after you and I are gone?”