Meet Our Teachers

Brian Borley

It’s the Stories Inside History That Make Students Care

After attending his first one-day Teaching American History seminar in March of 2019, Brian Borley thanked the district social studies coordinator who helped to schedule it. “I have taken a lot of professional development in the past 14 years,” he said, “and that one-day session”—on Landmark Supreme Court Cases—“was one of the best.”

Held at Borley’s own school (Port Washington High, about thirty miles north of Milwaukee, Wisconsin), the seminar had been organized through the Wisconsin Social Studies Council, and every social studies teacher in the state had been invited. The prospect of a university professor as facilitator convinced Borley to attend. Typically, professional development involves listening to a presentation on a new teaching approach. “You are told, ‘Here’s the idea; go with it.’ You don’t really have a content expert in the room.”

A Teacher’s Professional Evolution

Fifteen years ago, Borley graduated with a history major from Saint Norbert College. Later he earned a Masters in Education, studying with 30 teachers working in his local area and discussing their particular professional challenges. Borley, who at the time had many Russian immigrant students, wrote a thesis on how to help English Language Learners in social studies courses. The degree improved Borley’s teaching skills—but it did not build his content knowledge.

“Everyone leaves college thinking that they understand their content, but that first year they realize that they don’t know anything. There’s just too much.” Borley himself was assigned all sections of US History and World Studies at Port Washington. He found himself relying heavily on textbooks while focusing on forming “really good relationships with the students” and figuring out teaching practices that worked.

Now Borley teaches an “American Problems” course covering economics and government, including foreign policy and law. He also teaches a one-semester elective, “Current Issues,” in which students debate controversial policy issues and participate in a “moot court,” analyzing and arguing both sides of a hypothetical court case. Clearly, he enjoys leading students in discussion. He immediately appreciated the Teaching American History seminar style, in which a scholar expert guides teachers as they analyze and discuss primary documents of our history.

Interacting with a Scholar Expert

Professor Eric Sands (of Berry College in Georgia) facilitated the seminar, answering “every question we asked him,” Borley said. “It’s been so long since I’ve been in college that I’d forgotten how knowledgeable professors are.”

During the three 90-minute sessions, Sands had not done the usual: to lecture for an hour, then allow 30 minutes for questions. He invited the teachers’ questions throughout the session. To prepare for the seminar, teachers had read a packet of primary documents—majority and minority Supreme Court opinions as well as contemporary reactions to the landmark rulings. Moving through the cases, Sands had recounted the issues that prompted them. Borley already knew the general context of the cases, but not the details. “I get questions on the particulars in class—but don’t know the answers.” Sands provided “really helpful” information.

The teachers interacted with Sands throughout the day. “I asked a few questions, but I found Sands so knowledgeable that I mainly wanted to listen. I knew he was going to go somewhere interesting.” Borley was listening for the telling details that make a good story to recount to students. Students need a story to become engaged. “If you just say, here were the two sides to the case, and this side won, students are not going to care.”

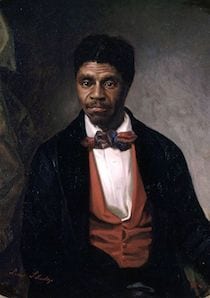

Contemporary Reactions to an Infamous Majority Ruling

Few of the stories around Supreme Court cases are more compelling and consequential than that of Dred Scott, a slave who in 1846 filed a lawsuit to claim his freedom. Scott’s owner had brought him with him when he moved out of the slave state of Missouri to the free state of Illinois and, later, to the free Wisconsin territory. Scott’s suit claimed that his enslavement should have ended when he was carried into a state and territory where slavery was illegal. When the court in 1857 issued a majority ruling against Scott, the opinion, written by Chief Justice Roger Taney, aroused outrage in the North and applause in the South. Historians cite the case as one of the factors precipitating the Civil War.

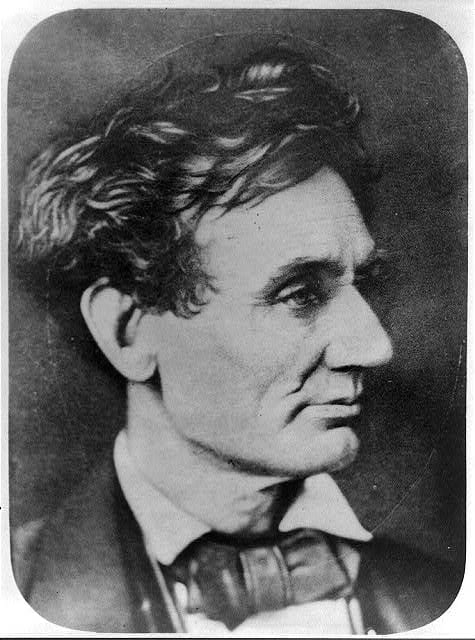

Along with opinions in the case, teachers read Abraham Lincoln’s speech critiquing Taney’s flawed reasoning, misrepresentations of history, and disregard of earlier decisions of the Court. Lincoln argued that Taney’s errors invalidated any claim that the opinion could set a new precedent. Respect for the Constitutional organization of government’s powers might have compelled Americans to accept Taney’s decision, Lincoln said, if it

. . . had been made by the unanimous concurrence of the judges, and without any apparent partisan bias, and in accordance with legal public expectation, and with the steady practice of the departments throughout our history, and had been in no part, based on assumed historical facts which are not really true; or, if wanting in some of these, it had been before the court more than once, and had there been affirmed and re-affirmed through a course of years . . . .

However, since

. . . we find it wanting in all these claims to the public confidence, it is not resistance, it is not factious, it is not even disrespectful, to treat it as not having yet quite established a settled doctrine for the country . . . .

Borley was fascinated to find Lincoln arguing that a Supreme Court decision need not be final. Lincoln suggested that “maybe we should wait for a series of courts to have the same opinion, and not let one single court’s decision set the precedent.” Teachers in the seminar “thought, this sounds good, but how would you do it, practically speaking? How often do you agree that there is a new court? Every year? Every ten years? Do you have to replace five of the nine justices before you have a new court?”

Who Holds Responsibility for Interpreting the Constitution?

Sands offered another perspective on the authority of the judicial branch. He drew teachers’ attention to a passage in Lincoln’s speech quoting President Andrew Jackson “declaring that each public functionary must support the Constitution, ‘as he understands it.’” Apparently, Lincoln thought all three branches of government responsible for interpreting the Constitution.

Sands offered evidence suggesting the wisdom of Lincoln’s view. He “mentioned that sometimes Congress will pass a bad bill—one that is Constitutionally suspect—while assuming that the Supreme Court will fix it. But then when it goes to the Court, the Court allows more of it to stand than they expected.”

Sands did not push Lincoln’s view on teachers, but he caused teachers to consider it. “He did a really good job of reviewing the powers of the three branches, including some powers they don’t use anymore. That was really helpful,” Borley said.

An Educational Investment With Long-Lasting Returns

Generous donors who want to improve civic education in America fund teaching American History’s free one-day seminars. Are these donors making a good investment? Borley thinks so. The program reaches teachers who will use what they learn.“Any teacher who goes to TAH events is first and foremost interested in their content area and wants to get better at it—otherwise they would not give up a Saturday or a teacher planning day.” These dedicated teachers will “see a minimum of 100 to 200 students every year, which means tens of thousands of students in the course of their career. . . . I don’t really see another investment that will reach more young people,” Borley said.

What more might Teaching American History do to support Borley and his social studies colleagues? “The best thing would be to offer more of these programs in our area,” Borley said. “As a member of the state-wide teacher union, I could help spread the word,” he offered. Borley was already planning to drive to Madison, Wisconsin after the school year ended to attend a Teaching American History seminar on the Vietnam War. “I think I have convinced two other colleagues to join me at it,” he added.