Meet Our Teachers

Carla Smith

Bringing History Alive in Three Dimensions

“I have always considered myself a three-dimensional teacher,” said Carla Smith, a graduate of the Master of American History and Government program. Smith teaches eighth grade history at Licking Heights Central Middle School. At this crowded suburban school east of Columbus, she works to generate the excitement that makes students ready to learn.

A lot of her students rely on free and reduced breakfast and lunch. Often, the parents of her students both work outside the home. They may receive little support with their school work, especially from Somali or Nepali immigrant parents who themselves are still learning English. Still, the children of immigrants bring to class their parents’ appreciation for America, an appreciation Smith works to build.

“I love telling stories,” Smith said. Adopting the personae of historical figures, she tells the story of history as if it were her own experience. “That draws students in,” Smith said, allowing her then to put students themselves inside of history.

It Begins with Primary Sources and Written Scripts

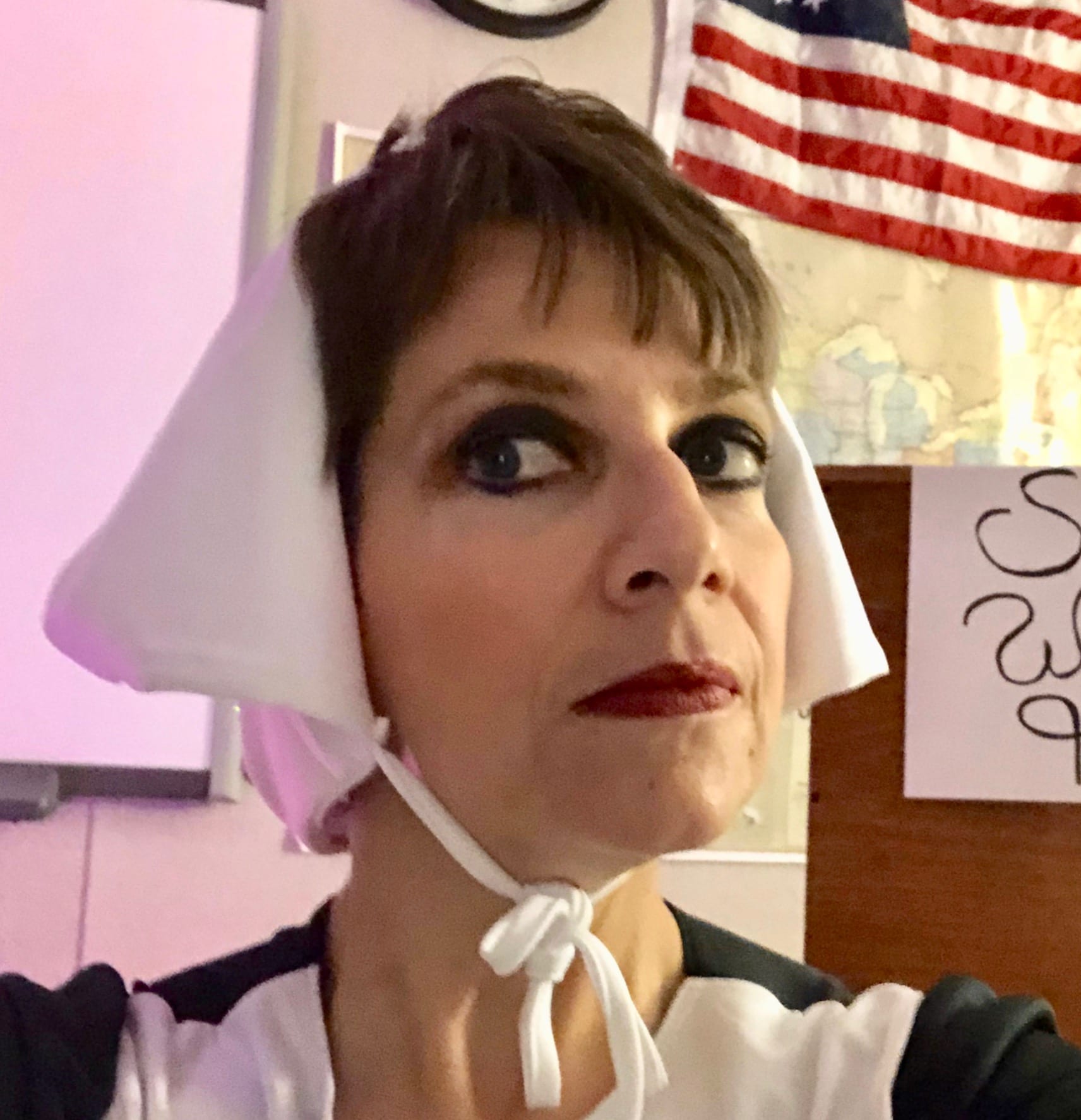

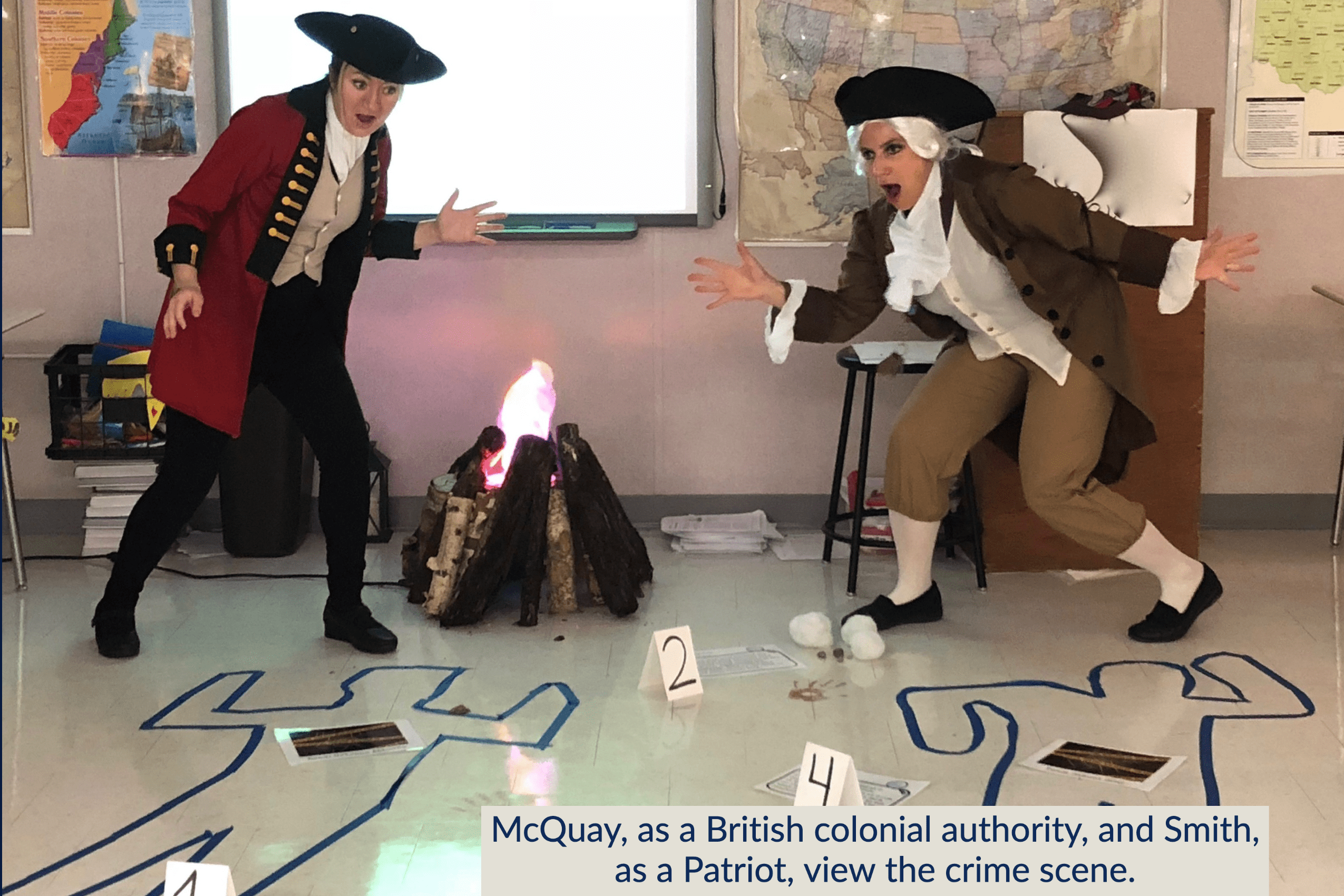

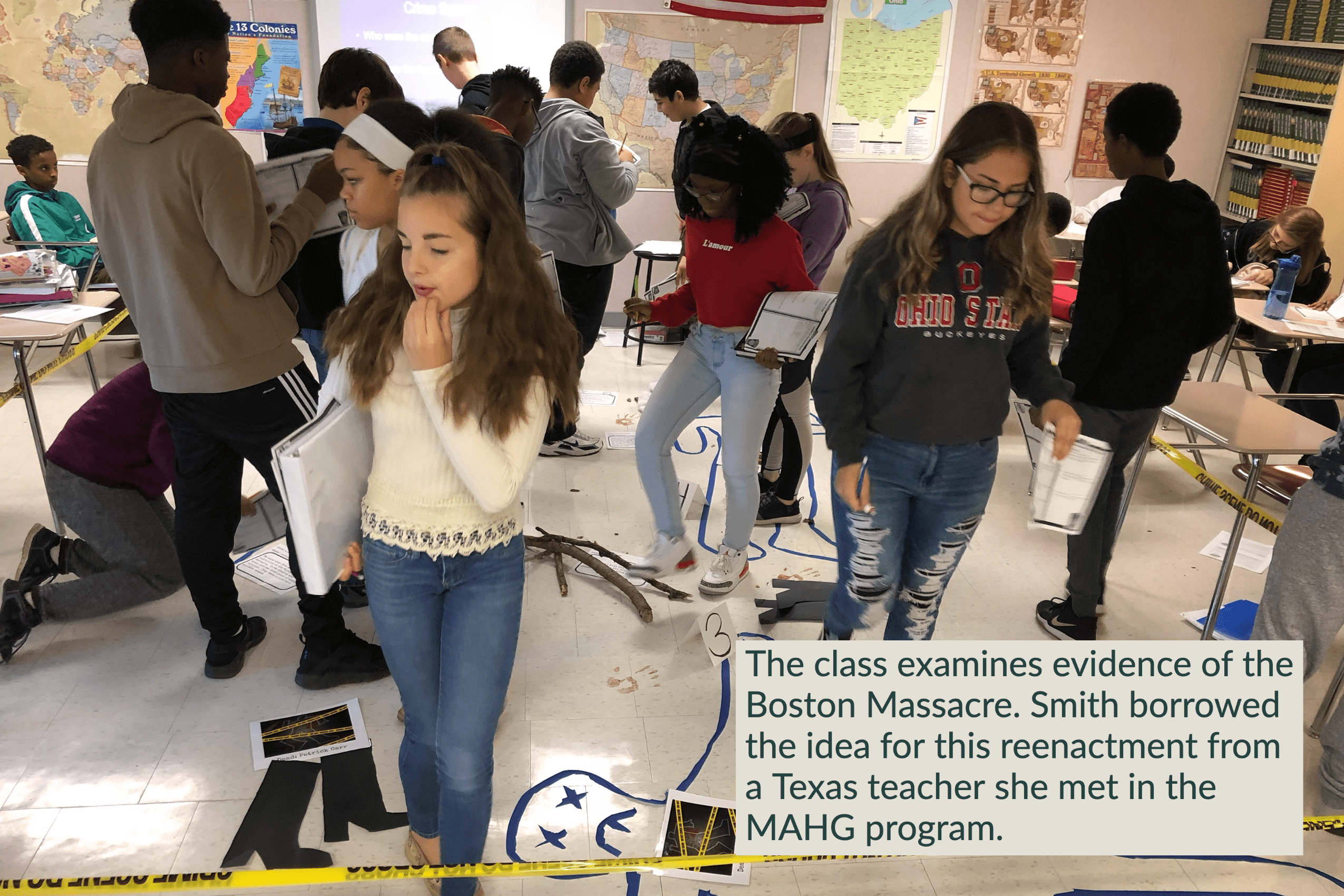

She teaches two sections of the school’s highest-performing students along with two sections of those who struggle most with learning disabilities. With both groups she uses costumes, props, and dramatic reenactments to bring to life decision points in American history. Students entering Smith’s classroom may find her dressed as an 18th century patriot, Shawnee warrior chief, or Civil War battlefield surgeon. What begins as Smith’s impassioned performance soon becomes a story in which each student plays a role.

She teaches two sections of the school’s highest-performing students along with two sections of those who struggle most with learning disabilities. With both groups she uses costumes, props, and dramatic reenactments to bring to life decision points in American history. Students entering Smith’s classroom may find her dressed as an 18th century patriot, Shawnee warrior chief, or Civil War battlefield surgeon. What begins as Smith’s impassioned performance soon becomes a story in which each student plays a role.

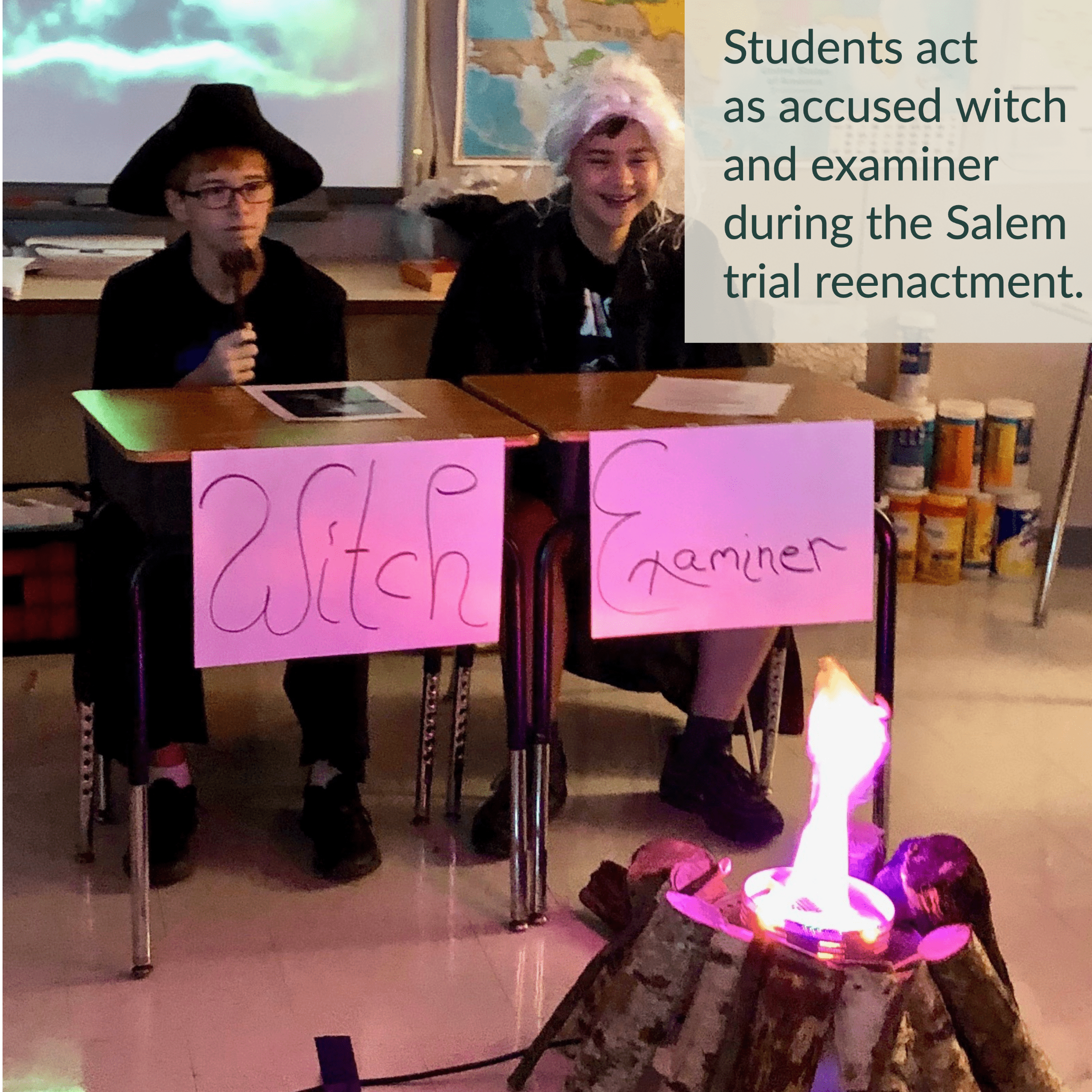

As the year begins, she helps students imagine “the adversities early Americans faced.” Teaching the Puritan experience, she gives students excerpts of documents related to Salem, Massachusetts and the infamous Witch Trials. As students read and answer document-based questions, “they pick up on the anxieties of those who settled in Salem,” Smith said. They struggled to grow crops in a short growing season, feared attacks from Native American tribes and jealously guarded property lines in disputes with neighbors. Meanwhile, they feared the “devil lurking in every corner to steal their souls.”

Then Smith recreates the trial. Wearing Puritan dress, she ushers students into a darkened classroom lit by a battery-powered hearth fire. She distributes a script based on her research into the actual backgrounds and fates of the accused. Each student reads the part of a magistrate, witness, or suspected witch. As they discover who is pardoned and who is condemned to death, they realize that making a confession—false or not—saved an accused person’s life.

Then Smith recreates the trial. Wearing Puritan dress, she ushers students into a darkened classroom lit by a battery-powered hearth fire. She distributes a script based on her research into the actual backgrounds and fates of the accused. Each student reads the part of a magistrate, witness, or suspected witch. As they discover who is pardoned and who is condemned to death, they realize that making a confession—false or not—saved an accused person’s life.

As Students Learn, They Create Their Own Roles

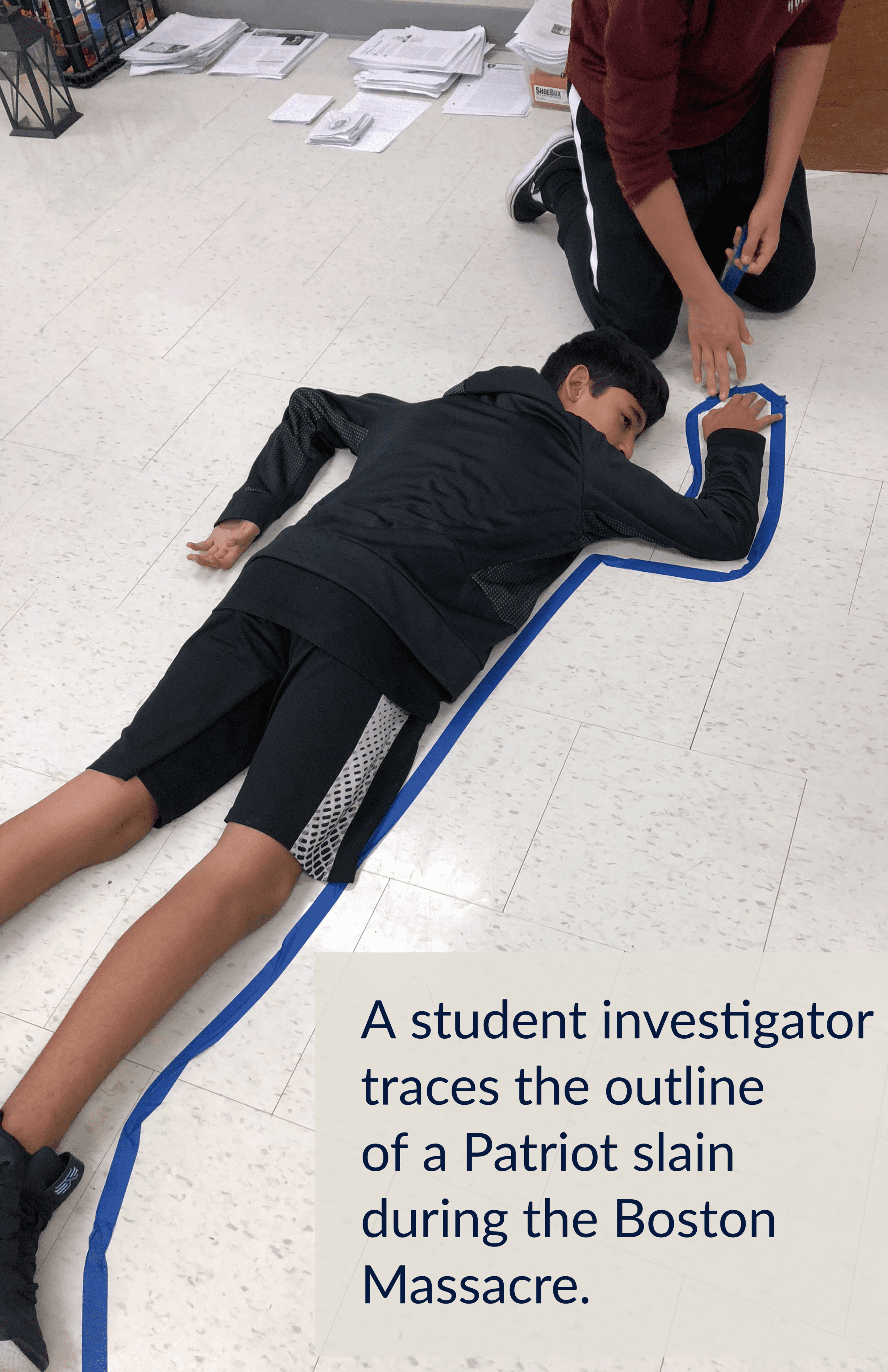

The year continues, and students step into new historical roles. Speaking as Loyalists or Patriots during the Revolutionary period, they debate the Stamp Act, the Boston Massacre, and finally, the decision whether to declare independence and go to war with Great Britain. As they come to “see both sides of the story, we end up having a surprising number of British sympathizers.” Recognizing the strength of the British position on American independence helps students grasp that the founding of our republic was neither inevitable nor easily accomplished.

Later, students reenact debates at the Constitutional Convention and the duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr.

The story of Shawnee Chief Tecumseh “is local history for us,” Smith said. Her own fascination with Native Americans led her to write a MAHG thesis on “The Fate of the American Indian in the Ohio Country.” In her classroom, Smith recreates the impassioned appeal Tecumseh made to tribes of the Ohio and upper Mississippi River valleys as he built a confederation to prevent white settlement in the Northwest Territory.

The story of Shawnee Chief Tecumseh “is local history for us,” Smith said. Her own fascination with Native Americans led her to write a MAHG thesis on “The Fate of the American Indian in the Ohio Country.” In her classroom, Smith recreates the impassioned appeal Tecumseh made to tribes of the Ohio and upper Mississippi River valleys as he built a confederation to prevent white settlement in the Northwest Territory.

“When the students enter the classroom on this day, they’ll again find the room darkened with my indoor fire blazing. Their desks will be arranged into tribal groups: Iroquois, Shawnee, Wyandot, Huron, etc. Wearing a chief’s headdress, I hop on top of my desk to address the tribes.” She reads John Dunn Hunter’s record of Tecumseh’s 1811 speech to the Osages. Afterwards, “students work in groups to learn about their respective tribes and create an argument on whether or not to join Tecumseh’s confederacy.” Some discover that their tribe “has already assimilated into American society and doesn’t want to go to war,” making the decision difficult. “Then we gather around the council fire and each group of Indians comes forward to tell Tecumseh their decision.”

The Pandemic Changes the Plan

When the pandemic shut down schools across Ohio last March, Smith sprang into action to assure the continuity of her students’ education. Her first priority was to provide students materials to work on, since, she said, “we’re not a district with one-to-one computers for all students.” Ohio Governor Mike DeWine announced that campuses would close after school on Monday, March 16. Smith suspected that the shut-down would actually occur on Friday, March 13. At 2 am that morning, she went to school to assemble activity packets for all 350 students in the eighth grade, including those taught by colleagues. “I photocopied primary source readings, short biographies, and a portion of the social studies textbook. Before the day ended, I got all the packets passed out.” Although the Governor stuck by his order to shut schools the following Tuesday, the school district decided not to wait. That Friday was the last day she saw her students in person.

Within two weeks, the school district loaned Chrome Books to students whose families lacked computers. The district used Google Classroom to post assignments and link to the on-line textbook and short informational videos. They scheduled weekly Zoom sessions between teachers and students in each class section. Yet many students were not doing schoolwork. Midway through April, Smith had still not heard from 40 of her 140 students. “A lot of my immigrant students don’t have internet access, or have to share a computer with their parents and siblings,” she explained. The district had implemented a pass/fail grading system for the last quarter, but passing required completing assignments. Before recording interim grades for the quarter, Smith spent a day trying to call the parents of students who’d dropped out of sight.

Lack of access to internet and computers was not the only problem. In some cases, “both parents are essential workers and therefore are leaving the kids at home alone while they work. I’ve been on several Zoom sessions where one student was making peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for his younger siblings while attempting to listen,” Smith said.

What’s Possible Online – And What Isn’t

She felt her advanced students were coping well with distanced learning. She worried about her struggling learners. Who would ensure they kept learning from home? “Even in the classroom, I have to stay right behind them, pushing. As we work through primary documents, I need to explain phrases and unfamiliar words. Some of these students have made tremendous strides in middle school, and we risk losing everything we worked so hard to accomplish.”

Moreover, “students at age 12 and 13 need to have hands-on experiences of history” in order to care about it. One of Smith’s chief goals as a teacher is to convey “the tremendous sacrifice earlier generations made” to build and preserve our Constitutional system. Hence her disappointment when the corona virus shut the school campus just as she began teaching Civil War history. “In that war alone, 620,000 Americans died to preserve the nation and our individual freedoms.”

She had planned to convey the human cost of the Civil War by showing how the weapons used in it eclipsed leaders’ understanding of battlefield tactics and medicine. She’d designed a new exercise recreating Pickett’s charge (“I had character cards made up for everyone”) and readied her usual “battlefield hospital.” Using “a make-shift surgery table and a virtual medical kit,” she simulates the amputation of a volunteer student’s leg. “It is not for the squeamish, but I have done this for years and never received a complaint. I first show the difference between the older musket balls and the minié ball used in the Civil War. The minié ball shatters bone, creating a deadlier wound that is more prone to gangrene.”

This year she’d teach the Civil War online, doing her best to keep students engaged. “Reaching every student remained a tremendous challenge. Yet I was able to transfer lessons to an on-line format,” she said. “For example, I found visual resources that helped students understand Civil War battlefield conditions. My advanced students continued learning American history through primary sources and discussion via Zoom. I helped my students with learning disabilities in small work sessions, also via Zoom.” But she could not create the three-dimensional experiences possible in the physical classroom. “There are some things you just can’t replicate on-line.”

This year she’d teach the Civil War online, doing her best to keep students engaged. “Reaching every student remained a tremendous challenge. Yet I was able to transfer lessons to an on-line format,” she said. “For example, I found visual resources that helped students understand Civil War battlefield conditions. My advanced students continued learning American history through primary sources and discussion via Zoom. I helped my students with learning disabilities in small work sessions, also via Zoom.” But she could not create the three-dimensional experiences possible in the physical classroom. “There are some things you just can’t replicate on-line.”

Staying Committed

Smith is planning for the new school year, which will be both on-line and in person. “During the first semester, a good portion of the student population will study only virtually,” she said. “However, some students have opted for a hybrid model allowing them into the classroom twice a week. When I have them in the classroom, I hope to engage them in the creative learning process.”

Reflecting on her experience in the Masters program, she says, “It was challenging. I gave up being department head while getting that degree. But after I finished, I missed being around other teachers in the program: people who are like-minded, who understand history and want to help their communities by teaching it. Such a void opened that I resumed my research on my thesis topic—which I hope to turn into a book. I also became a tour guide at the National Veterans Memorial and Museum in Columbus.” Smith will always share her passion for history and for what it means to be a United States citizen.