Meet Our Teachers

Charles Angus McDougall

Angus McDougall, a graduate of the Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) program, took all of his credits in the summer residential program. Living an hour and a half northeast of Ashland, Ohio, McDougall roomed on campus. But during his first summer in the program, he felt conflicted as Independence Day arrived.

“That’s a holy day for me,” McDougall explained. Each year he devotes a private hour to reading the entire Declaration, including the list of signers. “Then I spend the rest of my day with my family. In our small town of Hiram, Ohio we have a yearly Fourth of July softball game, with old-timers playing against young-timers. People who grew up here return to play, even from out of state. I missed this day for the first time in my life because I was at MAHG.”

That year, before a dinner of traditional cookout food for the Fourth, Peter Schramm (then Ashbrook Director) asked volunteers to stand and read the Declaration of Independence. Each MAHG student read several sentences, the final student reading the list of delegates. “I couldn’t hold it together. I had to walk out and call my brother to tell him about it. I knew that day that the MAHG program was something special and I was staying.”

Inspired by Team Teaching

McDougall loved the team-taught courses, especially “The Early Republic,” taught by historian and Jefferson scholar Rob MacDonald and political scientist Steve Knott, a Hamiltonian.

Their contrasting perspectives led to vigorous classroom debates. “Now I try to teach my classes that way. I expect passion and engagement.”

At Crestwood High School, McDougall teaches both Advanced Placement and dual enrollment US History and an elective on American wars. He also co-teaches a course he designed with colleagues in the science and English departments. He drew the themes of the course, and its team-taught design, from his MAHG experience.

Ohio Then and Now

It began as McDougall researched his Master’s thesis. Before narrowing his topic to the conflict in frontier Ohio between settlers and squatters (those who carried land deeds into the wilderness and those who had pushed, unauthorized, past the British-imposed boundary of the frontier), McDougall read about the settlers’ encounter with Ohio’s virgin forests. “We’re told that before settlement it was 97% forest, but I had no idea how big the trees were. There were trees 25 feet in diameter that people hollowed out and used for homes. Husband and wife teams, with maybe a couple of kids, spent their lives fighting Indians and trees. They had to girdle the trees, and wait for them to die, before cutting them down. Then there were the stumps!”

It began as McDougall researched his Master’s thesis. Before narrowing his topic to the conflict in frontier Ohio between settlers and squatters (those who carried land deeds into the wilderness and those who had pushed, unauthorized, past the British-imposed boundary of the frontier), McDougall read about the settlers’ encounter with Ohio’s virgin forests. “We’re told that before settlement it was 97% forest, but I had no idea how big the trees were. There were trees 25 feet in diameter that people hollowed out and used for homes. Husband and wife teams, with maybe a couple of kids, spent their lives fighting Indians and trees. They had to girdle the trees, and wait for them to die, before cutting them down. Then there were the stumps!”

Yet the settlers prevailed, replacing the forest with agricultural crops and decimating native wildlife. “I had no idea until I read the journals of Nicholas Cresswell that at the time of the Revolution there were buffalo and elk in Ohio,” McDougall continued. “In 1750, Ohio had more species of freshwater clams than the continents of Europe and Australia combined! If you cut down the trees, the rivers and streams get wider and shallower and warmer, and the cold-water species of fish and shellfish disappear.”

Now McDougall saw the rural Ohio landscape, with its quiet livestock and fodder farms, through a new lens. On his own home ground, human ambition had waged and won an epic battle against nature. Yet victory brought a tragic environmental loss.

Collaborating on an Interdisciplinary Experiential Academy

He read about other confrontations between man and nature. Excited by a historical study rich with science facts, he mentioned it to Andy Brown, a science teacher at Crestwood. Brown replied that he was reading a science book rich with history. It turned out both were reading Candace Millard’s River of Doubt, about Theodore Roosevelt’s exploration of a tributary of the Amazon.

McDougall and Brown began imagining a two-year, interdisciplinary program: “The American Experience Academy.” During year one, students explore “Ohio As It Was” in the time of settlement; in year two they explore “Ohio As It Is” today.

The program combines in-depth reading in history, science and literature with challenging hands-on projects. Both McDougall and Brown “saw early on [in our careers] that students – especially boys – were not doing well in the typical brick and mortar, bell to bell system of instruction.” Hence both developed “laboratory” lessons. “With the Cuyahoga River a five-minute walk from our building, Andy Brown had always done fantastic water studies with our students. I had incorporated ‘lab Fridays’ into my American Wars class. Students paint their faces in camo, eat MREs, and jump into Humvees. We’d seen these activities multiply students’ energy and enthusiasm.”

The program combines in-depth reading in history, science and literature with challenging hands-on projects. Both McDougall and Brown “saw early on [in our careers] that students – especially boys – were not doing well in the typical brick and mortar, bell to bell system of instruction.” Hence both developed “laboratory” lessons. “With the Cuyahoga River a five-minute walk from our building, Andy Brown had always done fantastic water studies with our students. I had incorporated ‘lab Fridays’ into my American Wars class. Students paint their faces in camo, eat MREs, and jump into Humvees. We’d seen these activities multiply students’ energy and enthusiasm.”

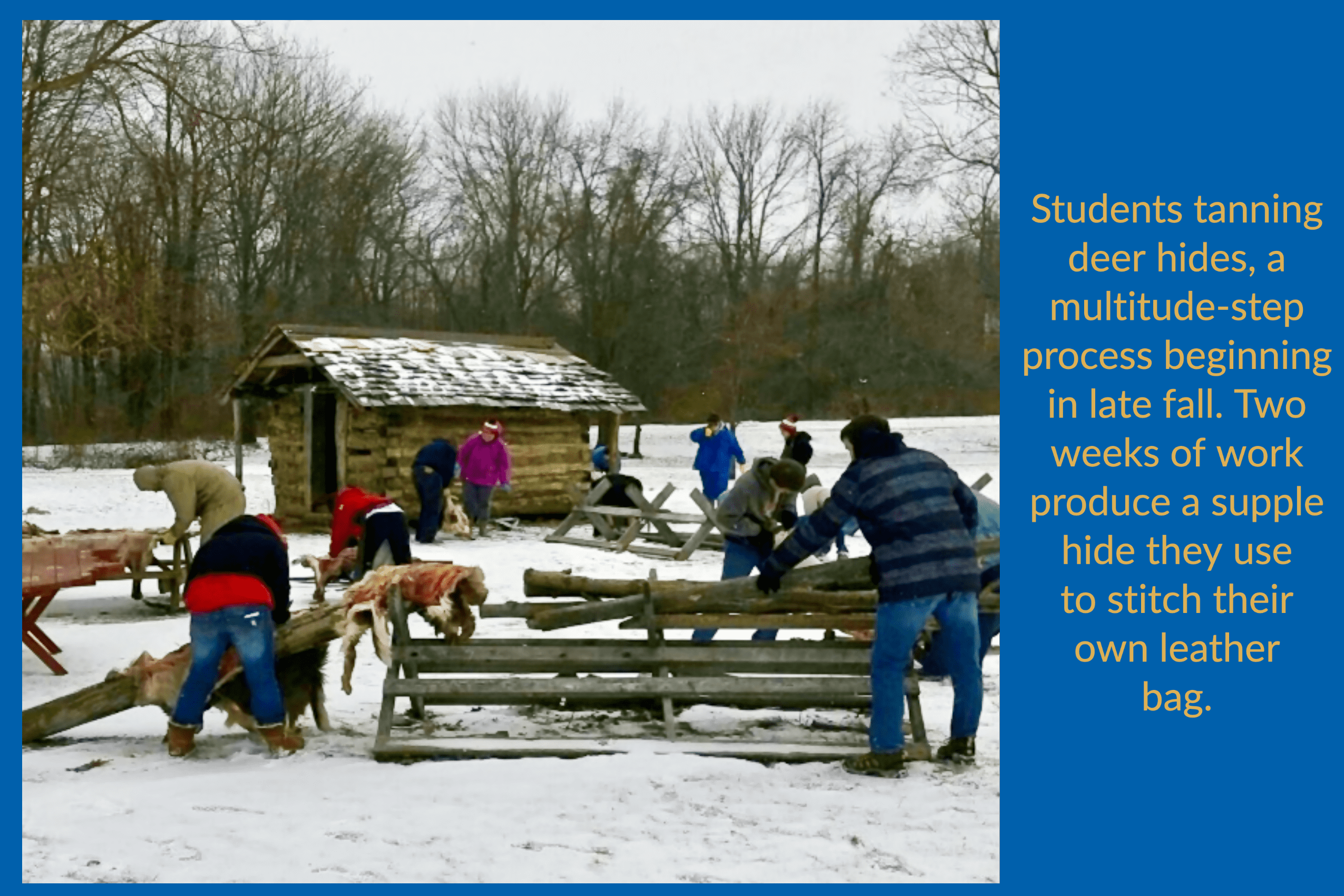

Historical assignments for year one include Cresswell’s journals and secondary studies by Richard White, Alan Eckert, and Fred Anderson. Students also practice early 17th century survival skills. They’re helped by local citizens and distant museum professionals.

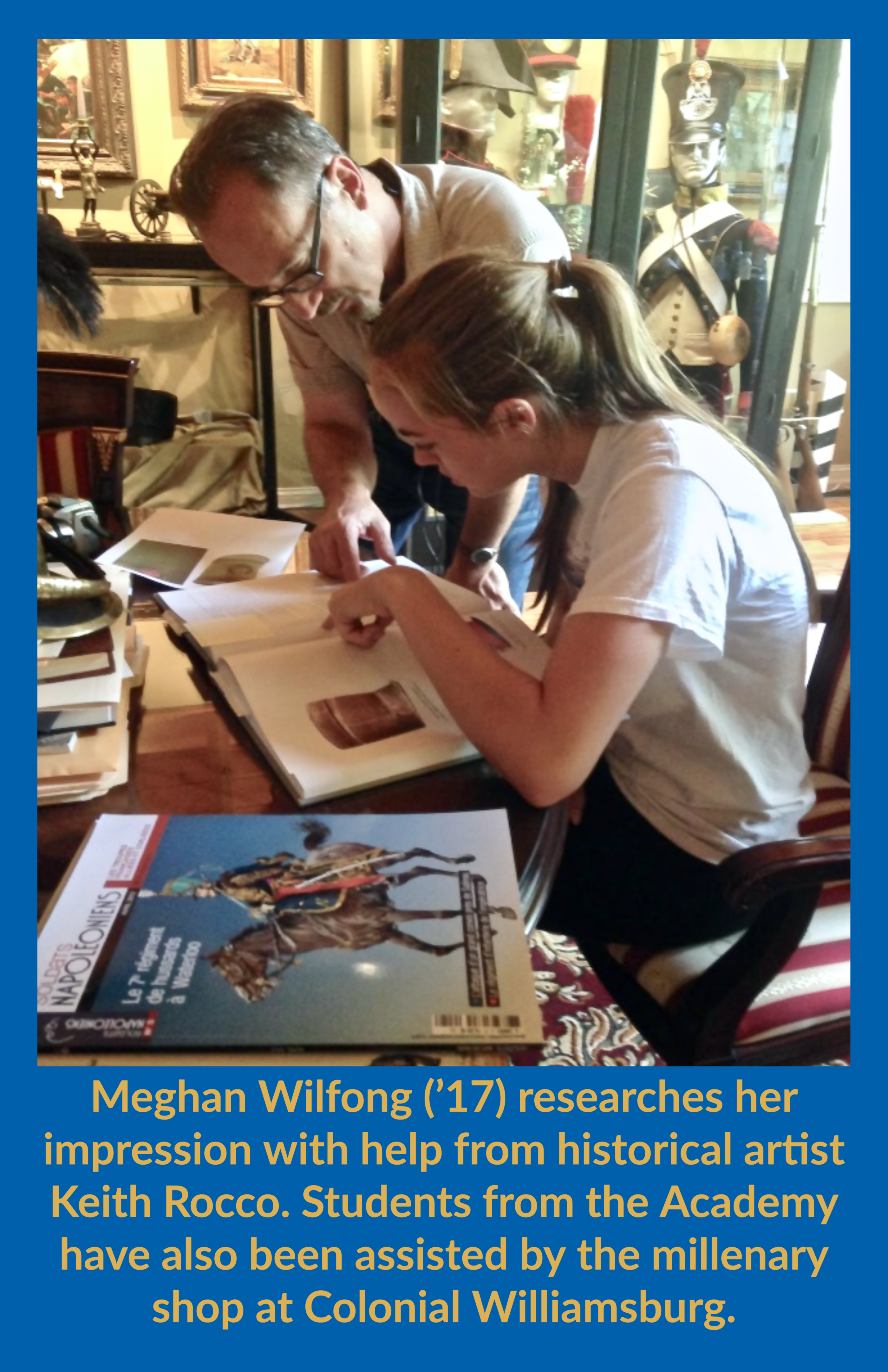

After a deer meat processor offered the program his deer hides, McDougall located a tanner who demonstrated how to tan hides and make leather goods. Today, each student creates an historically accurate 18th century outfit. “They consult with tailors from Colonial Williamsburg and sew an entire ‘period impression’ by hand in nine months, using only authentic materials: wool, leather, linen. They don’t use cotton, because the cotton gin was not invented until the end of the century.”

After a deer meat processor offered the program his deer hides, McDougall located a tanner who demonstrated how to tan hides and make leather goods. Today, each student creates an historically accurate 18th century outfit. “They consult with tailors from Colonial Williamsburg and sew an entire ‘period impression’ by hand in nine months, using only authentic materials: wool, leather, linen. They don’t use cotton, because the cotton gin was not invented until the end of the century.”

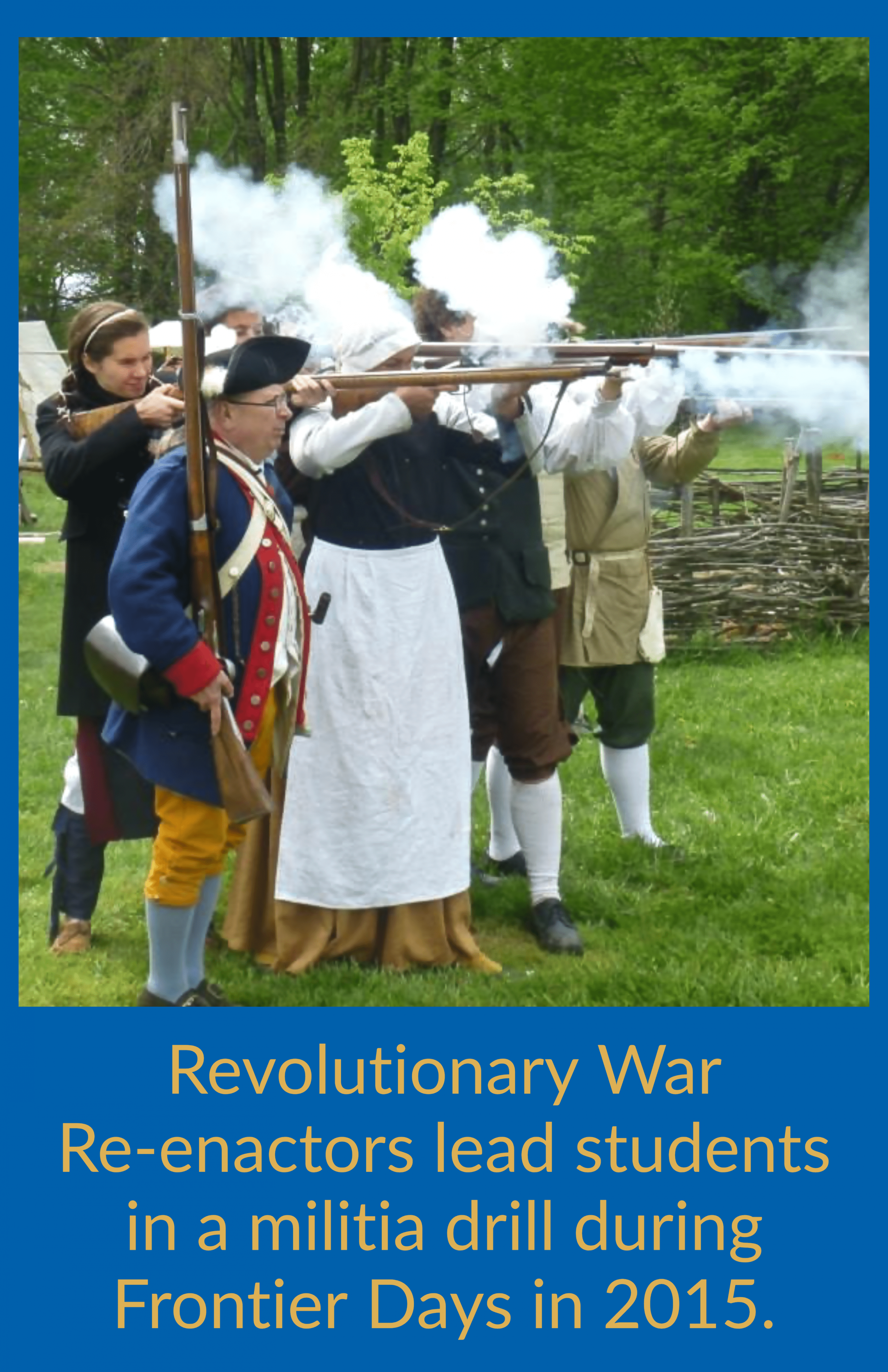

Wearing their finished outfits, students collaborate with historical reenactors to stage two weeks of “Frontier Days.” Visitors watch them construct a log cabin, cook over open fires, play native American games, and shoot muzzle-loaded flintlock guns. Those who’ve mentored the students admire the results. “Two students were offered internships at Monticello because of their beautiful leather work,” McDougall said proudly.

Building a Greenhouse

Year two of the academy focuses on intellectual and social movements developing during the latter 19th century that supported the modernization of both farming and industry in Ohio. Students read primary documents from the Progressive era along with secondary studies, including Richard Hofstadter’s Social Darwinism in Modern Thought. “We look at the science of modern farming, examining its ecological impact,” McDougall explained. “We study environmental degradation, the extirpation of wildlife, and changes in topography and climate.”

Although rural, the area around Hiram has few grocery stores. Fresh vegetables are readily available only at seasonal farmers markets. An early American Academy class brainstormed a greenhouse where students could grow fish in tanks and practice aquaponics in all seasons. Successive classes “worked for five years writing grants and planning the design with an architect,” McDougall said. They finished building the greenhouse in mid-March. One day after installing the fish tanks, COVID-19 shut down the school campus.

With students homebound, McDougall and his science colleague took turns caring for the fish, until Hiram College agreed to “foster-parent them for the summer.” But this was not the celebratory spring the teachers had planned.

The Limits of Distanced Learning

McDougall led Zoom-based discussions of the readings he’d assigned. This worked for his more bookish students. Other students seemed less engaged.

McDougall led Zoom-based discussions of the readings he’d assigned. This worked for his more bookish students. Other students seemed less engaged.

Some of these students are kinesthetic learners. “They need a physical outlet during the intense academic experience of the academy.” Others need concrete challenges to make historical reading fully meaningful. Imitating the activities of earlier Americans helps them visualize the past. Building a state-of-the-art greenhouse helps them imagine the future.

Moreover, “students who are hand-stitching their own impressions take personal ownership of them,” McDougall explains. “They talk to museum curators and realize they have to get it right. They can’t just buy a pair of moccasins off the Walmart shelf; they have to make their own. Their investment in this work carries over to the documents and books they read. They begin joking and laughing about Nicholas Cresswell like he’s a personal friend,” McDougall says.

Ultimately, the academy teaches life lessons. McDougall speaks of high school graduates who return to tell him “the academy gave them a sense of purpose. It taught them what they were capable of.”

It’s unclear how pandemic will affect the 2020-21 school year. If students begin the projects for Academy Year I, perhaps they can use “Flipgrid” video software to show their work in progress to the museum and costume design experts who normally help them. That’s a big element of the Academy, McDougall says. Museums want to interact with the public, and “it’s important for kids to know such educational resources exist. Too often we walk through life and we don’t see the stuff that’s right in front of us.”

McDougall was named 2018 Ohio History Teacher of the Year by the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

You can watch scenes from a recent “Frontier Days” reenactment exercise in a video made by alumni of the American Experience Academy.