Meet Our Teachers

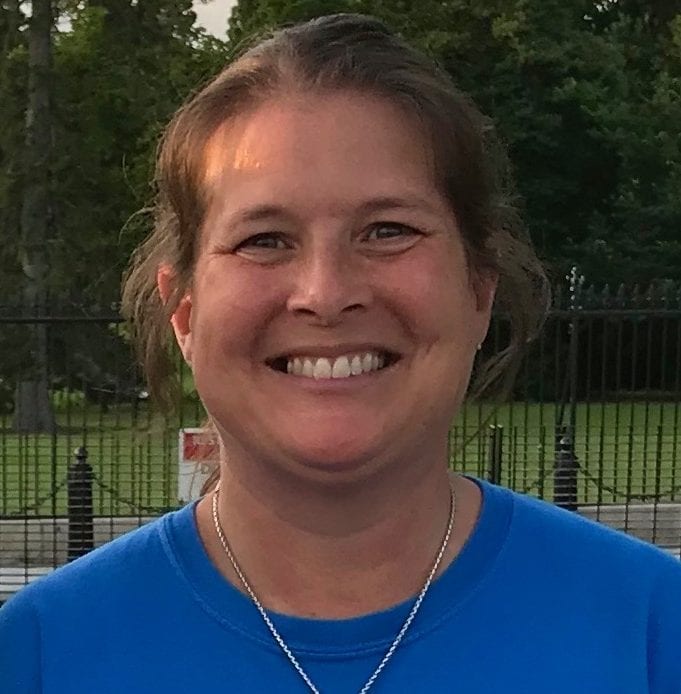

Debbie Napier

A Teacher Changes Focus, Building Reading Skills and Changing Lives

What began as a job change for family convenience became a passion for Debbie Napier, an eighth grade social studies teacher at Harlan County Middle School, in Harlan County, Kentucky. It would not have happened had Napier not discovered Ashbrook’s Teaching American History programs.

As a young graduate of Lincoln Memorial College with a BA in science and social studies education, Napier landed her ideal job. She would lead a pilot program in “Activity Center Science Education” at a middle school near where she had grown up. She directed a laboratory where students mastered science concepts through hands-on activities, and she supported fellow teachers by bringing extra science lessons into classrooms. “For eleven years, I got to play with science!” she said.

After her family built a home in another part of Harlan County, Napier wanted to move to the nearby school campus. She’d taken enough history courses in college to earn a minor specialization in social studies, so she was offered a job in that field, with the promise she could return to running a science lab when a job opened.

Falling in Love with Social Studies

During her first year as a history teacher, Napier scrambled to get up to speed, learning each lesson in the district-issued textbook the night before she taught it. The next year, she took a professional development seminar in Louisville on the Constitutional Convention. The seminar was led by Professor Gordon Lloyd, who had poured his encyclopedic knowledge of the American Founding into an interactive exhibit at TeachingAmericanHistory.org. Lloyd’s lively presentation on the personalities, issues, and daily debates at the 1787 convention—based on such first-hand accounts as the meticulous daily record kept and later published by James Madison—inspired Napier to go deeper into primary sources.

She applied and was accepted into TAH’s summer 2011 Presidential Academy. It was a three-week seminar exploring critical moments in US history—the Founding, the Civil War, and the Civil Rights Movement—through primary texts and visits to historical sites in Philadelphia, Gettysburg, and Washington, DC. Napier returned from the academy with three binders of documents, ready to put them to work in her classroom.

That fall, Napier’s new principal was ready to fulfill his promise to return her to a science job. “But by then I had fallen in love with social studies,” she recalled. The activity-based science curriculum, she knew, was fun to teach and fun for students. But getting kids to like social studies, she realized, would require the passion of a teacher on a mission.

Asking Permission to Do More for Students

So Napier told her principal, “Thank you, but what I want now is a reading class to teach in addition to 8th grade American history and 6th grade world geography. I need a supplementary course for eighth graders in which we read longer excerpts of primary sources.” Napier’s principal pointed out that reading courses were taught as part of English language arts and according to Common Core standards. Napier agreed to cover those standards while addressing the history, arguing that the extra course would help students score well on the state-mandated tests in both areas. The principal was persuaded.

A year after the experiment began, standardized test scores in language arts and social studies rose, and “the principal closed the door on my classroom and let me do what I wanted.” Six years later, Napier is still doing it, using classic American novels and autobiographies, along with biographies and selections from key primary documents, to get students thinking about what self-government means.

“We do a leadership analysis of each text, talking about how it shows individuals making decisions.” Reading the contrasting biographies of George Washington and Benedict Arnold, students start to grasp the steady persistence and sense of duty that earned Washington lasting respect. Tom Sawyer confronts students with another leadership style, that of the charming, wily, self-promoting boy who is the hero of the novel. Students complain about reading a 340-page novel and about Twain’s ironic style. “‘Why does he talk all around the subject instead of getting right to the point?’ they ask. But eventually they are caught up in Tom’s adventures. The book prompts some of our best conversations,” Napier says.

Napier also drives home the connection between education and self-government. Students read the dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451, in which an authoritarian society outlaws books; examples of antebellum slave codes which prohibited educating slaves; and a section of The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An Ex-slave, in which Douglass’s master angrily ends the reading lessons his mistress is giving him. Then students write an essay to answer the question: Is literacy necessary for liberty?

Since the Presidential Academy, Napier has taken advantage of every one-day and weekend Teaching American History seminar available to her. Two years ago, she took a further step, enrolling in Ashland’s Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) program. She already holds a Masters in education; but a degree in her content area would qualify her to move to the high school level to teach Advanced Placement or dual credit courses. “I love my eighth graders!” she insists, but someone needs to remind older students of the principles of the American founding. Napier’s sense of mission is pulling her toward that next work.

In the meantime she uses strategies—many picked up from teacher friends in Ashbrook programs—to teach fundamental concepts students will not soon forget. Before Napier’s students ever read the Declaration of Independence, they read excerpts of Locke’s Treatise on Government that explain the theory of natural rights underlying Jefferson’s words. Then Napier hands each student a scissored-out sliver of the Declaration to memorize overnight. The next day, students discover how their quotation fits into Jefferson’s complete argument for self-government. As Napier points, in the order of the text, to the students who hold each line, they recite and slowly re-construct the text, beginning with When in the course of human events and ending with Let facts be submitted to a candid world.

“We’ve just read the Declaration,” Napier announces. “Now go home tonight and figure out what your part of the text means.”

“Teaching the concept of natural rights is not in the eighth grade standards,” Napier admits. “But if you help students grasp the basic philosophy of our system of government, they’ll learn the rest.” They’ll soon decode the language of Jefferson. This is essential, Napier says. “Our kids will only grasp the principles of the Founders if we’re reading what the Founders wrote.”