Meet Our Teachers

Ethan Brownell

Ethan Brownell has been named the 2023 Maine History Teacher of the Year by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Brownell teaches humanities at a “town academy” in Pittsfield, Maine, the Maine Central Institute (MCI). In his 12 years at MCI, Brownell has covered a wide range of courses, including AP US History, AP US Government and Politics, Sociology, 11th grade American History & Government, and the Model UN course for students who choose that extracurricular. A TAH multiday seminar on the Founders’ political philosophy helped Brownell renew his content knowledge, he told TAH staff. He also told us about his school and teaching practice.

As a “town academy,” MCI is the local high school for several towns in rural central Maine—Pittsfield, Detroit, Burnham, and a couple of others; but 30% of our students are private boarding and day students. The students who board come from around the world. For students from the local area, the school gives them a great opportunity to mix it up with students they would never otherwise meet.

A Thematic and Interdisciplinary Approach to History

Our curriculum is interdisciplinary. I’m part of a humanities department that covers both social studies and language arts. This past year, we completely revised our humanities curriculum. Some of our history courses were just not connecting with students; students didn’t understand the cultural, intellectual and political context in which events occurred. This year we’re making more time for that context by taking a more thematic approach to history. I am teaching juniors, and teaching almost entirely early American history and government. We’ll talk about the founding era, study the US Constitution in detail, and then we’ll examine the ways the Constitution has been tested and challenged during our history. We’ll look at the era of Jackson and the controversies over the balance of power between the states and the federal government. We’ll study the sectional crisis, examining Constitutional provisions that led to that crisis; we’ll study the Civil War and constitutional questions regarding the status of the seceded states; we’ll study the Constitutional amendments passed at the end of the war and during Reconstruction. Then we’ll talk about civil rights movements from the mid twentieth century until today.

I’m also teaching a new elective on Death and Dying. We’ll first consider how different cultures have dealt with death throughout history; then we will study the practical issues we’ll all have to deal with, like how to care for those who are dying; how we process grief; how to deal with the material things left behind; and so on.

It’s a good thing that I love to learn, because just as soon as I’m confident that I’ve got a good grasp of my content area, I learn that I’ve got to teach something different! One year, I had a senior European History class and had to teach the French Revolution. I had never studied it, but I had the skills to teach myself and knew how to locate good histories of it. Teaching that course confirmed that I love teaching political history and political philosophy—the backbones of our current political institutions, the source of our political ideas and how they have changed over time.

TAH Seminars Are Opportunities to Learn, Think, and Connect with Other Professionals

Anytime I can be a student, without paying thousands of dollars for it, I’m going to do it. When I received an email inviting applications to Teaching American History’s multiday seminars, I jumped at it. The email came just as things were opening up again after the pandemic. I was invited to a seminar at the Coolidge Library in Northampton. It was led by Professor Jason Stevens of Ashland University and it focused on the political philosophy that informed the thinking of the American founders, and finally on Lincoln’s interpretation of those ideas.

It was great. We sat together trying to unpack the primary documents we’d read in preparation for the seminar, asking each other questions and bouncing ideas off each other. Stevens did a great job of directing the discussion and helping all the teachers interact. I always love meeting others who are doing the same work I do, hearing their teaching ideas and their stories about their classrooms.

Understanding the Leaders of the Past—By Demystifying Them

What I find most interesting in history—the development of political thought and political systems—can lead to a focus on the major figures of history, the “great men,” at the expense of lesser-known actors. I try to add additional voices to the history I teach, when primary sources are available. Still, you can’t ignore the great leaders—they were major forces in their time. But you can demystify them in some ways.

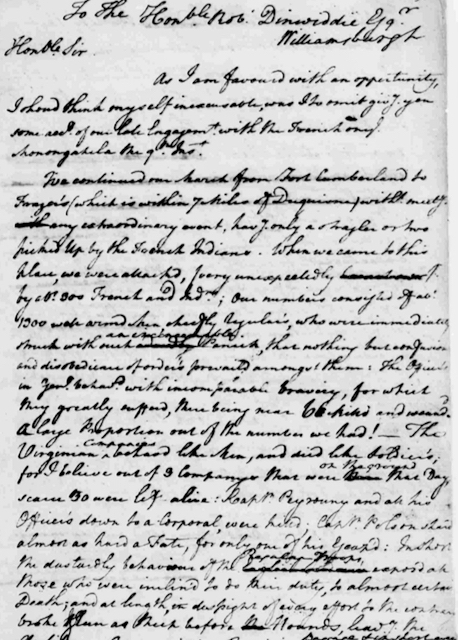

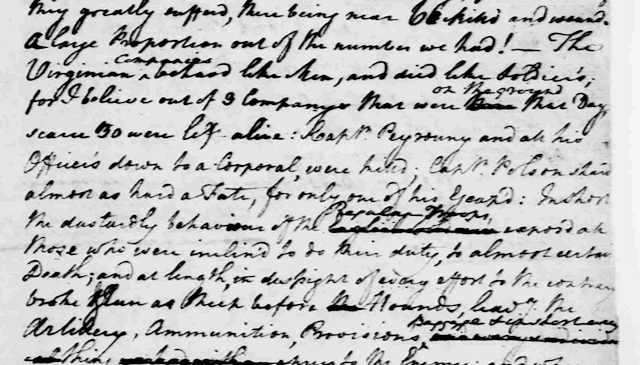

Washington, George. George Washington Papers, Series 2, Letterbooks -1799: Letterbook 2, March 2 – Dec. 6, 1755. March 2, – December 6, 1755. Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/mgw2.002/>.

One of my favorite primary sources in American history is a letter I present to students without revealing the author. I tell them it was written to Virginia’s colonial governor, Robert Dinwiddie, after the Battle of Monongahela. But I don’t tell them it was written by 33-year-old Colonel George Washington, commander of the Virginia regiment. Washington reports a debacle: most of the officers are dead; the troops retreated under fire; he had two horses shot out from under him. (It’s amazing that he did not die himself.) I ask students to unpack that document. It’s written in Washington’s own kind of shorthand, and the version we read is directly transliterated from the original—you can see his edits, where he struck out phrases and then wrote something else. Sometimes students say, “This guy can’t spell!”

Then I ask them to guess the identity of the author. They are amazed when I tell them it’s George Washington, a man who lucked himself out of dying in battle an unbelievable number of times. It’s fun to demystify this American hero, so celebrated for his dignity and self-control, who at first reacts to a traumatic event in the emotional way most of us would. At first, he excoriates the “dastardly behavior of the English soldiers,” then he crosses through “English soldiers” and replaces that with the more euphemistic “regulars.”

When we study great Americans, we need to remember their humanity. They felt the same emotions we do. They had their own flaws and eccentricities. But neither were they just like us, except in funny clothes; they lived in different times and faced a different set of pressures. Abraham Lincoln is a good example. Before concluding, during his presidency, that emancipation was a military necessity, did he really want to abolish slavery? We can look at various vignettes in his life for evidence, but we also have to consider his historical context. During the Lincoln–Douglas debates, he talked about limiting the spread of slavery, but not about abolition. Could he have said, “Slavery should be abolished”? No, he could not—that just was not a politically viable position in Illinois at the time. Could he have thought that? Could he have wanted emancipation to come as soon as possible? Absolutely. But politics being the theater of the real, you get what you can get.