Meet Our Teachers

Jason Berling

“I have the most important job in the world,” says Jason Berling. Teaching AP United States history and government at Seton High School in Cincinnati, Berling prepares young Americans for responsible citizenship. “We are a self-governing republic. The founders, understanding human nature, structured our constitutional government to ensure the maximum possible good. But this structure remains a machine at the discretion of its owners.” Berling helps students understand this machinery and “the logic behind it,” so they can participate in shaping the American future.

How a Teacher Found His Calling

Berling didn’t initially choose this vocation. He pursued a criminal justice degree at the University of Cincinnati, planning a career in law. When he graduated, in 2010, the recession had dimmed prospects for such work, and a few days in law school persuaded him the profession was not for him. He took as job as an Executive Team Leader for Assets Protection at a Target store, tracking and preventing business losses due to unsold inventory and theft. Three years in the demanding position gave him the hands-on equivalent of a business degree—but little personal fulfillment.

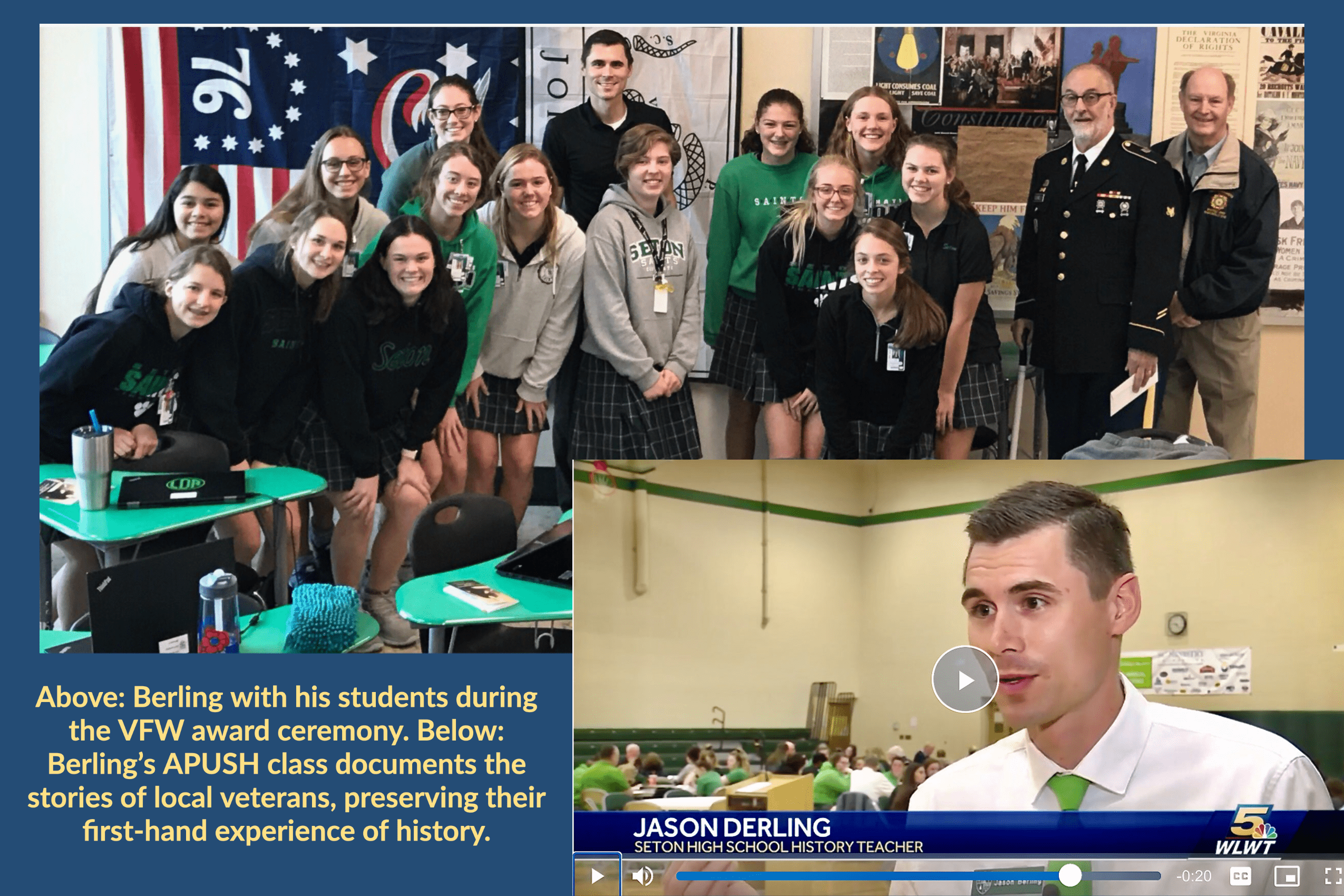

Volunteering to coach track at Seton High, a Catholic all-girls school founded by the Sisters of Charity, Berling found mentors who helped him discern he was called to teach. Later, his study in the Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) program would allow him to become the teacher he wanted to be.

First, Berling entered a Master of Education program at his alma mater and began doing substitute teaching. “To make ends meet, I took any substitute job offered. I built a network of contacts, while learning how teachers in a range of subjects worked.”

Making History Class a Laboratory for Investigations

He wanted to teach history and government, making his classroom as engaging as the science classrooms he’d entered while substituting. “In science class, students put things under a microscope, study them, and draw their own conclusions. I wanted to apply this concept of hands-on learning to history.” After completing his MA and being hired to teach social studies and English to seventh-graders at Our Lady of the Visitation School in Cincinnati, he devised history lessons as “investigations.” A trip to Monticello inspired his first idea: an investigation of Thomas Jefferson. How should Americans view Jefferson?

He wanted to teach history and government, making his classroom as engaging as the science classrooms he’d entered while substituting. “In science class, students put things under a microscope, study them, and draw their own conclusions. I wanted to apply this concept of hands-on learning to history.” After completing his MA and being hired to teach social studies and English to seventh-graders at Our Lady of the Visitation School in Cincinnati, he devised history lessons as “investigations.” A trip to Monticello inspired his first idea: an investigation of Thomas Jefferson. How should Americans view Jefferson?

“I put together a lesson plan, using primary sources and other evidence, to gradually reveal things about Jefferson my students didn’t expect.” Explaining the mudslinging presidential campaigns of the early republic, Berling gave students the newspaper article written by disappointed office-seeker James Calendar, who alleged that Jefferson had made a concubine of his enslaved servant Sally Hemmings. Then Berling gave students facts about slave life at Monticello and Jefferson’s own views on slavery and race, drawn from biographical materials Monticello supplied. Finally, he presented students with excerpts from an article detailing a study of DNA evidence from the descendants of Jefferson and Heming. The seventh graders “got drawn into the drama” of the story. When he asked them to assess Jefferson, “most said, ‘it’s complicated!’” Berling recalls. He felt his approach was working when the class took up the Declaration of Independence. Having considered what Jefferson might have done, “they were even more interested in what he said.” The investigation had transformed Jefferson from a “marble monument” into “a real human being” who articulated “ideals that still inspire us today”—even if he could not live accordingly.

MAHG Study Opens a World of Primary Documents

Soon afterward, Berling was hired to teach US history at Seton High School. He was thrilled to teach at the school he’d come to love through coaching work. “But I was not where I wanted to be in my content knowledge.” During his first year at Seton, he applied for and was awarded a Madison fellowship. He immediately enrolled in MAHG. Its live online seminars and summer residential program fit his working teacher’s schedule—and the courses, unlike many he’d taken for his education degree, were meaningful. “By the end of my first summer week, I was totally swept up in the program, realizing how awesome it was.

“As I worked through the MAHG program I was able to replace reliance on the textbook with documents that I’d studied.” He now knew how to place these sources in historical context and answer questions about their interpretation. “I flipped my priorities. Primary sources became the framework for the class.” In the meantime, Berling’s social studies colleagues at Seton were retiring and being replaced with recently graduated education majors. Berling assumed leadership of his department. “We collaborated to build a department culture of appreciation for primary sources—building that from the ground up.”

At Seton, freshmen study world history, sophomores study US government, and juniors study US history. “Certain documents recur in all three courses”—particularly the Declaration. “They first study the Declaration as an example of enlightenment thinking in the Age of Revolutions. In sophomore year, they study its implications for the structure of our government. When it comes up again in US history, we look at it as an historical document. What events led to it and what happened as a result of it? Does the argument in the list of grievances hold up to historical scrutiny?” Students also compare the Declaration to other historical sources. Freshman look at other declarations of independence, such as that of Haiti. Sophomores may compare it to John Adams’ “Thoughts on Government.” Juniors read primary sources revealing the public attitudes that supported the Declaration. “In all of these cases, they’re reading the same document, but it’s never repetitive. I could not have imagined structuring our courses this way if it weren’t for the MAHG program.”

At Seton, freshmen study world history, sophomores study US government, and juniors study US history. “Certain documents recur in all three courses”—particularly the Declaration. “They first study the Declaration as an example of enlightenment thinking in the Age of Revolutions. In sophomore year, they study its implications for the structure of our government. When it comes up again in US history, we look at it as an historical document. What events led to it and what happened as a result of it? Does the argument in the list of grievances hold up to historical scrutiny?” Students also compare the Declaration to other historical sources. Freshman look at other declarations of independence, such as that of Haiti. Sophomores may compare it to John Adams’ “Thoughts on Government.” Juniors read primary sources revealing the public attitudes that supported the Declaration. “In all of these cases, they’re reading the same document, but it’s never repetitive. I could not have imagined structuring our courses this way if it weren’t for the MAHG program.”

Berling still designs history lessons as investigations, but now he builds them entirely around primary documents. One investigation asks students to determine what caused the Civil War. He begins by asking students their opinions. “They are all over the map on the question,” he says. Then he presents the first piece of evidence, Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address. Lincoln presents the conflict between the North and South as a test of whether the union will be preserved. Berling follows with the secession declarations of Southern states, or Alexander Stephens’ Cornerstone speech. Students see the Confederates frankly acknowledging “it’s all about slavery.” A speech by Frederick Douglass, perhaps “The Slaveholders’ Rebellion,” confirms this view, but adds that the war will show slaveholders that the Constitution does not support them. Then students read The Gettysburg Address, in which Lincoln calls the war a test of the principle of human equality; the Emancipation Proclamation; and finally the Second Inaugural Address. “Now they have layers of documents supporting different conclusions. I say, ‘Tell me what caused the war.’ They have to evaluate what they’ve read and decide.”

He stages similar investigations of Woodrow Wilson’s reasons for abandoning neutrality over World War I and of the constitutionality and effectiveness of New Deal policies. “Sometimes I’ll divide the class up into three groups, giving each group a different pair of documents. One group may be led to one conclusion, another group to a different one. When the groups talk to each other, they are surprised to learn of the evidence the other group examined.”

Teaching daily with primary documents “opens up a whole world of respectful conversation grounded in historical evidence,” Berling says. Finding evidence in the documents for their interpretive claims slows students down, making conversation thoughtful instead of emotional. As students learn the inside history of ideas and events, Berling adds, they adjust their unexamined assumptions. Both those most critical of our history and those most patriotic learn, again, that “it’s complicated.”

Above all, Berling wants students to appreciate “the good in America,” understanding that it flows from the system the founders—flawed, yet thoughtful men—designed. Knowing this, they can work to uphold and “improve upon the American tradition.”

Watch a local TV news video that describes the project.