Meet Our Teachers

Jennifer Jolley

As the 2020 school year begins in Florida, a months-long pandemic continues, putting new demands on teachers. Jennifer Jolley has spent the summer rethinking her lesson plans so as to meet the challenge. Yet she admits to feeling like a first-timer.

She has dedicated 27 years to her profession, and was just named 2020 Florida Social Studies Teacher of the Year by the Gilder Lehrman Foundation. Resourceful and adaptable, she has taught social studies in a variety of school settings. She spent seven years as a middle school teacher, including three years overseas, before moving to high school social studies. Today she teaches government (honors and regular) and AP courses in both US and comparative government at Palm Bay Magnet High School in Melbourne.

She has never stopped learning both on and off the job. Awarded a Madison Foundation Fellowship to pursue a Master’s degree, she earned it in Ashland University’s American History and Government program. Later, she spent a summer in Florida Senator Bill Nelson’s office as a Madison Foundation Congressional Fellow, gaining insights into the functions of Congress. In the summer of 2019, she was named Summer Institute Coordinator for the Madison Foundation. Spending summers at the institute, she will renew her understanding of our Constitutional system while troubleshooting the logistical issues of new fellows.

Through these programs and other teacher institutes, she’s gained a network of colleagues with whom she constantly shares pedagogical ideas.

Still, this fall, Jolley and her colleagues must master an entirely new instructional model: a “hybrid” system in which in-person and online teaching occur synchronously.

The Challenge of Hybrid, Synchronous Learning

To accommodate students who feel returning to campus is unsafe, teachers will open “a Google or Zoom meet during each class period, communicating with students at home while we teach those in front of us.” At the same time, “we’re switching to a block schedule, with 90-minute, instead of 45-minute, class periods. It does mean we’ll have fewer students each day”—a moderate safety measure during a pandemic. Jolley will now teach her semester-long courses in 9-week sessions. But with 300 students to teach this year, she’ll still see 75 students daily. Meanwhile, two days’ lessons must fit into one, giving students less time to process new concepts. “That’s a major paradigm shift.”

As she revamped lesson plans for the doubled-up, hybrid format, Jolley decided “to put everything online for all of my students. That way the students sitting in front of me will get the same instructions as those at home.”

The changes wrought by the pandemic will reshape Jolley’s lesson plans. “All the activities I’ve developed over the years involve students working together or talking together. I like to schedule ‘civil conversations’—using a format recommended by the Constitutional Rights Foundation. This is also the format of the seminars I took in Teaching American History’s Master’s program: Socratic and participatory.” Yet in a classroom of 25 students, it would be impossible to leave any space between desks if she arranged them in a conversational circle. Placing students together at work tables for shared projects and small group discussions is also unsafe.

“It killed me. I set up my room like I do for standardized testing. All the desks facing forward and spaced as far apart as possible”—hardly two feet. “Now they’ll all be talking to me”—not to each other.

“So, I’m planning for collaboration online.”

Options for Online Collaboration

Over the summer, Jolley researched online strategies and participated in online seminars, familiarizing herself and others with new online tools. She was already a fan of the online games offered at the iCivics website. Another, newer set of resources Jolley likes is “Engaging Congress,” a project of the Center for Representative Government at Indiana University. “It’s an online game that uses primary sources—many of them images—from the Library of Congress. This summer I helped promote and train teachers in the program in five different webinars. It teaches history, government, economics. My students absolutely love it. It’s an app, so students can install it onto their phones.”

She experimented with teaching software, some of which requires a paid subscription for full functionality. She likes “Edpuzzle,” which “allows you to combine questions with videos.” When Jolley’s school district subscribed to “Nearpod,” she became a certified educator for it, finding it particularly useful. Because the subscription was cancelled, Jolley looked for free programs that gave her the same options. Nearpod, along with “Pear Deck” and “Padlet” use live, interactive slides. Padlet, for example, helps students collaborate in building interactive maps, timelines, “word walls” and other online visuals. These programs also allow for comment boards. “Say I project a political cartoon. Students can post alongside an interpretation or a question about it. On my computer screen, I can see and screen their comments before allowing them to appear to the class as a whole.”

She found many online tools integrated easily with Google Classroom, the program used at her school. Already a Level 1 Google Certified Educator when the pandemic began, she helped teachers at her school master it. Colleagues she’d met through MAHG, the Madison Foundation, TAH weekend programs, and other institutes shared their ideas for online teaching with her, through Facebook groups and Twitter. “The teachers I gravitate toward are always learning.” At her own high school, a STEAM magnet school, teachers formed a professional learning network when the pandemic sent instruction online last March. “We had a chat network, then met daily to talk through technical problems. It gave us a trusted environment for collaboration.” Such collaboration strengthens teachers to ride out the pandemic. “It boosts your mental state. It helps you embrace new things.”

Uncertainties Remain

Unfortunately, funding shortfalls at the district level may limit teachers’ options. Synchronous in-person and online teaching “requires more technology,” Jolley says. “In my classroom, my school laptop connects to a bigger monitor viewed by students in the classroom. But that monitor lacks a microphone. If I’m on a Zoom call, I’d have to unplug the monitor from the laptop—turning it off—so that students working from home can hear me.” To get around the problem, Jolley bought her own webcam.

Palm Bay Magnet has “one-to-one” technology due to a grant that, five years ago, bought laptop carts for each classroom. The laptops are now old, and, a week before school began, many were missing. They had been loaned out to students’ families when online instruction began last March.

Good Teachers Adapt

Hence Jolley’s uncertainty as she planned for hybrid instruction. It’s not the first time she’s had to reinvent her methods. In 2014, she transitioned to her current job so as to be near her parents, retirees in Sebastien, Florida. Unlike those at her former school, located in an affluent white suburb of Boca Raton, her new students feel economically insecure. They lack confidence that education leads to success. When she began at Palm Bay, her students’ behavioral and academic issues caused her to wonder, “‘What’s wrong with me? I’m a good classroom manager!’”

She realized that she’d have to work harder to develop a rapport with her new students. She’d grown up in a comfortable blue-collar home. After earning her undergraduate degree, she worked three jobs while taking further courses to earn accreditation to teach in Florida. She’d always worked hard at her calling. Yet in her students’ eyes, she was a person of privilege.

The influence of socio-economic background became clearer to her when her former school, Marjory Stoneman Douglass, suffered a horrific shooting in 2018. “I was not a bit surprised that those students responded to the tragedy with the March for Our Lives movement,” Jolley said. “They were already politically active when I was there. They came to me to ask if they could host a political forum with invited elected officials.” Their aspirations inspired Jolley “to work harder”; yet teaching them AP US Government was, comparatively speaking, “a breeze. I had almost the whole year to prepare students for the AP exam. I gave students primary documents and we had good conversations about them.”

Learning, Like Political Change, Takes Time

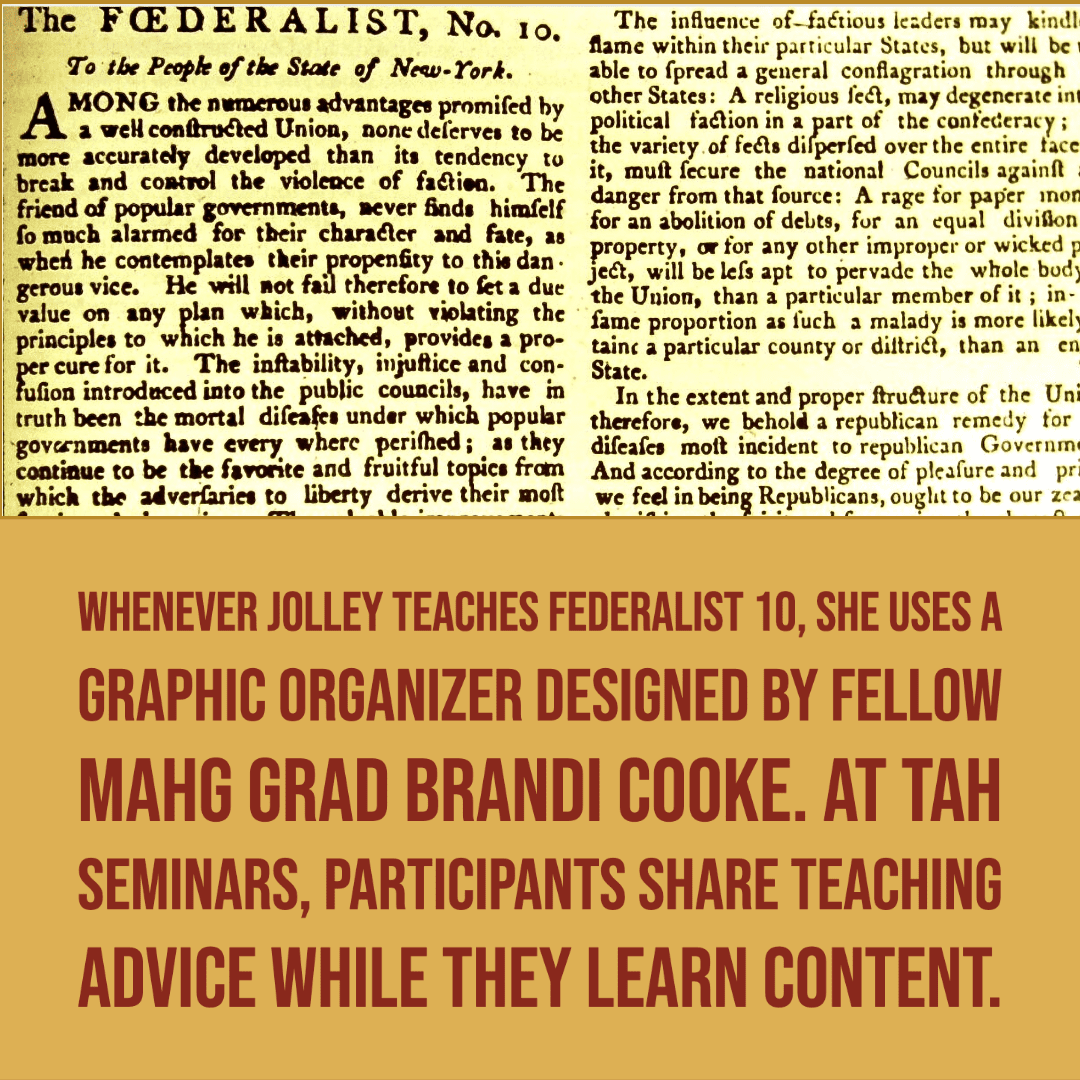

At Palm Bay Magnet High, students’ hesitancy about education inspires Jolley to work harder. Working through a single primary document may require two days, a large chunk of the new block schedule. Asked to read Federalist 10 overnight, many students will not, being put off by its length and complexity. The next day’s lesson will entail “a Socratic discussion while I walk them through important paragraphs.” The following day, as she checks students’ recall of what they learned, “they’ll have questions.” Yet this will signal success. Students’ questions show they are “trying to process the reading and figure out how to explain it themselves.”

Jolley noted that whenever she teaches Federalist 10, she uses a tool designed by fellow MAHG graduate Brandi Cook—a visual organizer that traces Madison’s complex logic. When she took the course on The Federalist with Professor David Foster, he shared Cook’s graphic with the whole class. “This is gold!” teachers said. TAH seminars aim to give teachers content knowledge, not teaching advice. Yet participants share teaching advice while they learn content.

Jolley noted that whenever she teaches Federalist 10, she uses a tool designed by fellow MAHG graduate Brandi Cook—a visual organizer that traces Madison’s complex logic. When she took the course on The Federalist with Professor David Foster, he shared Cook’s graphic with the whole class. “This is gold!” teachers said. TAH seminars aim to give teachers content knowledge, not teaching advice. Yet participants share teaching advice while they learn content.

Just as she works to overcome students’ skepticism of education, Jolley combats their cynicism about American politics. “As Madison said, enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm of government,” she reminds students. Elections may not bring thoughtful leadership. “But even without voting, people can exert power. Women did, prior to getting the vote a century ago. They picketed, protested, and changed legislators’ votes. Think of the Civil Rights Movement, which brought the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It just takes time for protesters to gain respect.”