Meet Our Teachers

Jody Glass

Jody Glass helps students see around the obstacles that constrict their vision of who they can become. She’s in her sixth year of teaching, a second career for her, after spending a decade as a youth minister. Her current studies in the Master of Arts in American History and Government program help her teach students to see themselves as full participants in our constitutional system.

While a minister, Jody realized, “I see these kids once, maybe twice a week. They’re at school all day.” To really help them, “I need to be in the schools!” At age 34, she went back to school—to Western Kentucky University—to earn a dual degree in history and secondary social studies education. She chose social studies in order to help students “function in society” —and because “I love history,” she said.

Inspiring Higher Aspirations

She first taught at a private school that served an affluent population in Kentucky. “I taught professors’ and doctors’ kids,” she said. “They knew what they wanted and had a plan for their lives.” This year, after her husband’s job relocation, she began teaching at Anderson County High School in Clinton, Tennessee, a rural town northwest of Knoxville. Her current students are growing up in very different circumstances from those of her earlier students. For the young men, “it’s an accomplishment to graduate high school and move on to a job as a welder or electrician. College is not expected.” For young women, marriage is the goal, and it’s an achievement to graduate before bearing children. “We have a daycare in our high school,” Glass said, “and if we can get young mothers to finish school, it’s a big deal.”

She’s struggled to recalibrate her expectations, but not to relate to her new students. She grew up in poverty, in a community where few aspired to attend college. “My husband and I both rose above that. We’re educated. Now,” Glass said, “I want to pour myself into” helping students pursue bigger dreams.

Progress, Not Grades

Glass teaches dual credit and Advanced Placement American History. Although dual credit courses are intended to give high school students early college credit hours, they function as the general level history course at Glass’s school. Operating on a limited tax base, the school adopted the dual credit requirement to earn a federal funding incentive. Unfortunately, the strategy has not worked; only a tiny minority of students pass the achievement test that triggers the extra funding. Glass’s students are not ready for a college-level course; they have not yet developed the necessary reading skills.

This doesn’t discourage Glass. Although her students begin at a skills disadvantage, they learn. Glass makes sure they see the progress they make. She gives them a pre-assessment at the beginning of the semester, then gives them the same test at the end. Seeing the score improvement surprises and encourages them. “It’s not about the grades; it’s about what you learn,” she tells students.

Finding the Perfect Classroom in MAHG

Glass’s teaching approach solidified when she began her MAHG studies during the 2021 summer residential program. “I walked into my first class and I thought, ‘Wait, this is an exchanging of ideas! People are reading, then they’re bringing their thoughts about the reading to the table. We are feasting together upon this information. I fell in love with program; it fit into my idea of the classroom perfectly,” Glass said.

When asked, she acknowledges that MAHG seminars feel familiar, because they encourage the careful inquiry into written texts that she undertook in seminary. MAHG students discuss the context and the purpose of each primary document while “dealing with conflicts within the text. You have to dive deep to reach understanding.”

Deep diving is best done in the company of knowledgeable guides and eager fellow learners. Glass is impressed by her MAHG professors’ grasp of their subject matter. “You know they enjoy talking about it. It’s like any classroom, right? If you as a teacher get excited about the material, your students will, too, no matter how old they are.”

She also learns from her fellow teachers in the program. Listening to their comments on the readings, Glass often finds herself thinking, “Never in a million years would I have thought of that.” MAHG, Glass says, is “a free space in which free thinkers enlighten each other.”

How Glass Helps Struggling Readers

Glass wanted to bring the primary documents she was studying in MAHG to her students. At first, this didn’t go as well as she’d hoped. Even at her former school, “the majority of my students didn’t read very well; they definitely couldn’t read primary sources that are intricate, detailed, and dense. . . . They’re used to reading mobile phone texts and emojis; we’re going back to Egyptian hieroglyphics, I guess,” she mused. She had to figure out “how to take the structure that I know works in the MAHG program into my classroom on a day-to-day basis.”

She adopted a “think, pair, share” approach—students read a primary text on their own, thinking about it; then they talk about it with a partner; then each partnered pair shares their observations with the class. To deepen and solidify students’ understanding, she uses Socratic seminars. Her students prepare for these by working through written questions, finding support for their answers in the primary documents they are reading. This helps students cite evidence more fluidly during the later discussion.

“In my first years of teaching,” Glass explained, “a colleague told me, ‘When you enter a classroom, you should see the students working—not the teacher.’” The teacher should have “done her work ahead of time;” she is present to “scaffold thinking,” to guide, and to suggest a new path of inquiry when students are “stuck or going in the wrong direction.” Glass adds, “One day, my hope is to become a master questioner.” Professors in the MAHG program, she says, pose questions that push students to engage an author’s ideas at a high level.

Since she began teaching at her current school, where many students are “below-level in reading and writing,” Glass has changed her approach in only one respect: she uses much shorter excerpts of the primary documents she covers. She doesn’t use the “modernized” paraphrases of primary documents that some teachers present to struggling readers. “I don’t like doing that. I want them to read the original language. Otherwise, you lose so much of the meaning. It’s the difference between eisegesis and exegesis,” she says, referring to the principle she followed in her seminary studies. Instead of bringing to the text what you expect to find, “You should pull meaning out of the text.” When students struggle with unfamiliar words, she points them to the dictionary.

Individual Liberty and Social Progress

As she teaches US history, Glass helps students uncover a unifying theme: Americans’ ongoing attempt to balance their commitment to individual liberty with their hopes for social progress, while grounding both pursuits in the realities of human nature. “Left to themselves, people don’t necessarily do the right thing; they choose themselves over others,” she says. The founders’ grasp of this reality, and their belief that human selfishness most often appears in abuses of political power, led them to frame the Constitution and Bill of Rights in ways that protect individual freedoms against government impositions.

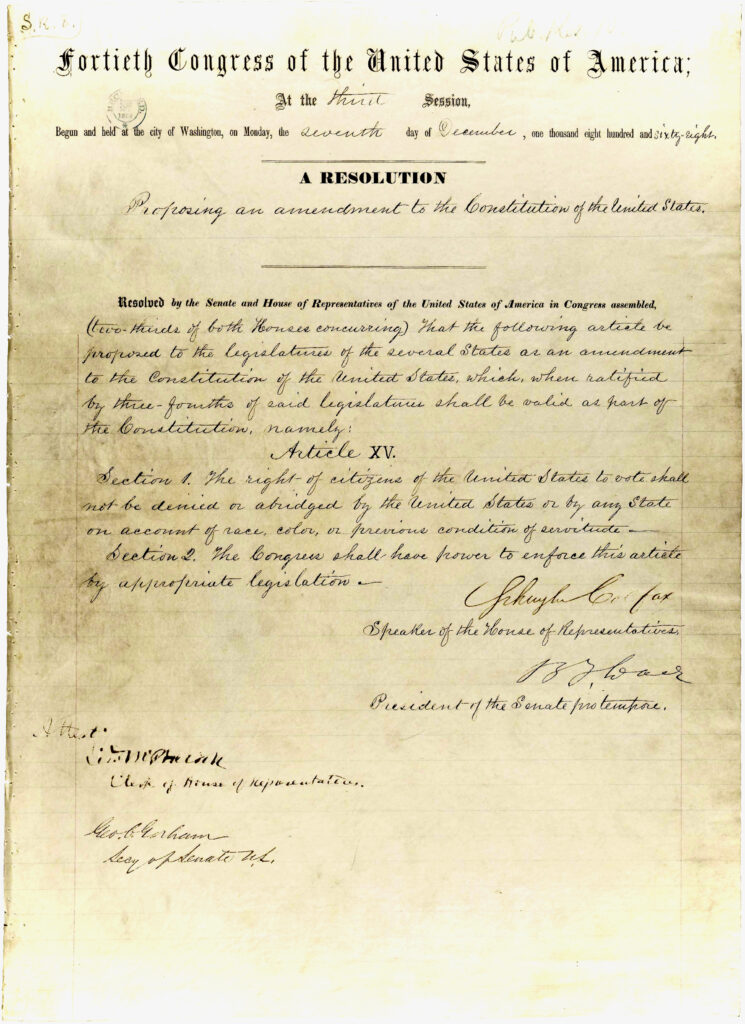

During Reconstruction, Congress “introduced new rights” that, once confirmed as constitutional amendments, now needed to be protected by the federal government from infringements by the states. “So, at first,” she says, “we’re limiting the power of government; then we’re extending it” to accomplish “the same purpose”—the protection of individual rights.

Those who later espoused progressive policies often relaxed attention to individual rights while empowering government to reform business and labor practices, housing conditions, and other social ills. Because of human nature, these reforms were not always successful. “You can’t explain the rise of late-twentieth century conservatism unless you understand that,” she points out.

Glass Encourages Questions

“I love constitutional law,” Glass says, because of the way it circles around the problem of protecting individual rights while making room to improve the community as a whole. Students share her interest in this. Glass recalls a recent lesson on the Gilded Age and progressive attempts to restrain the power of big business. “Ms. Glass,” a student asked, “doesn’t this relate to debates over electric cars today?”

“You’re onto something; I can feel it,” Glass said. “What do you think is the connection?”

“Well, hasn’t the state of California passed a law saying they will fine people if they don’t purchase electric cars by a certain date?” Living in an area where used cars are the norm, the student was incredulous at what he took to be an infringement of individual rights.

Glass explained that California is banning the sale of new cars that are not electric by 2035. But as discussion continued, students wondered if the law had been influenced by lobbyists for the electric car industry.

“They make these connections all the time,” Glass said. “I encourage them to make their voices heard when they don’t like what is happening” in civic life. Jody Glass helps students “understand our constitutional system” so that they will know how to engage in it.