Meet Our Teachers

Kelly Steffen

Talking Across the Generations About History

“The vision of the founding fathers—and of all the other extraordinary people who carried our republic forward after it was founded—will come to nothing if our students do not see the value of participating in self-government,” says Kelly Steffen. A graduate of Ashbrook’s Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) degree, Steffen teaches to pass on the legacy of the founding and of those who have worked to complete it. Her lesson plans often create opportunities for students at Vinton-Shellsburg High School in Vinton, Iowa to learn from older community members. This helps them appreciate the problems faced, sacrifices made, and progress achieved by earlier generations.

In 2019, the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History named Steffen Iowa History Teacher of the Year. She was nominated for this award by a colleague in English language arts with whom she co-teaches a sophomore humanities class on 20th Century America. Being nominated meant filling out an award application that documented her teaching philosophy and practices. As part of the application, Steffen described a study unit she assigns in the humanities class (and simultaneously in a class on American history from 1945 to the present).

Creating a Cold War Museum Around Primary Documents

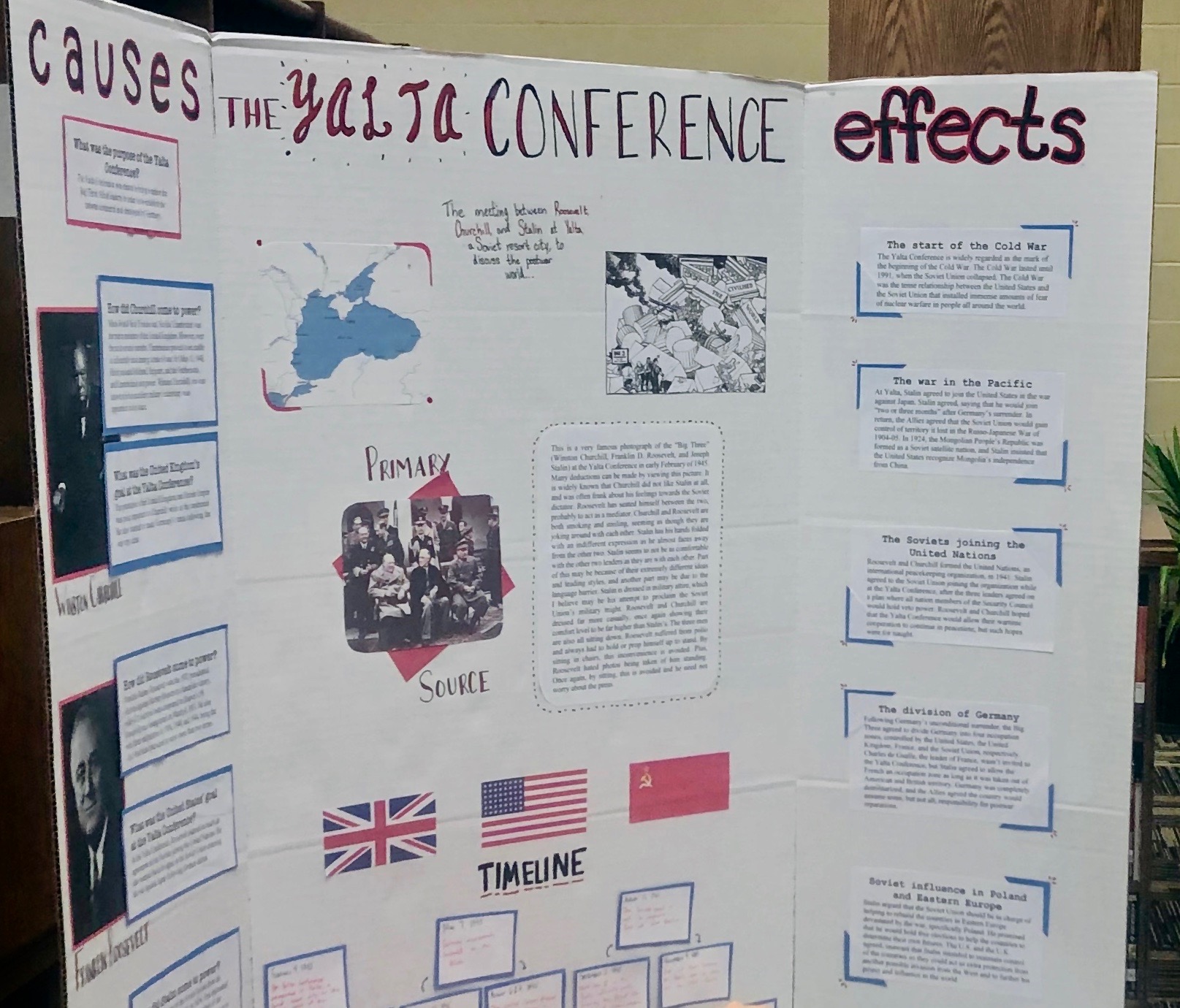

Each year Steffen’s students create a “Cold War Museum.” Working singly or in pairs, students become specialists on an historical figure or theme from the period. Then they structure an exhibit around at least one primary document that gives important insights into their topic. “I saw the value of primary sources during my time in the MAHG program,” Steffen says. The words of those who witnessed history as it unfolded capture the imaginations of both students and museum-goers.

Each year Steffen’s students create a “Cold War Museum.” Working singly or in pairs, students become specialists on an historical figure or theme from the period. Then they structure an exhibit around at least one primary document that gives important insights into their topic. “I saw the value of primary sources during my time in the MAHG program,” Steffen says. The words of those who witnessed history as it unfolded capture the imaginations of both students and museum-goers.

Students create visual displays that place the documents into historical context. They add simple, concise text explaining the causes and effects of events mentioned in the documents and defining any unusual vocabulary in them, such technical terms, acronyms, or slang of the era.

Some students take rather creative approaches. “I’ve had students build models of the Berlin Wall. Once a student working on the creation of NASA brought in a telescope and devised a hands-on viewing experience.” Students spend about two weeks preparing their displays before the “preview day,” when they present their work to fellow class members, who critique it. After two more days of post-peer-evaluation tweaking, the museum opens to the public.

The Benefits of Cross-Generational Conversation

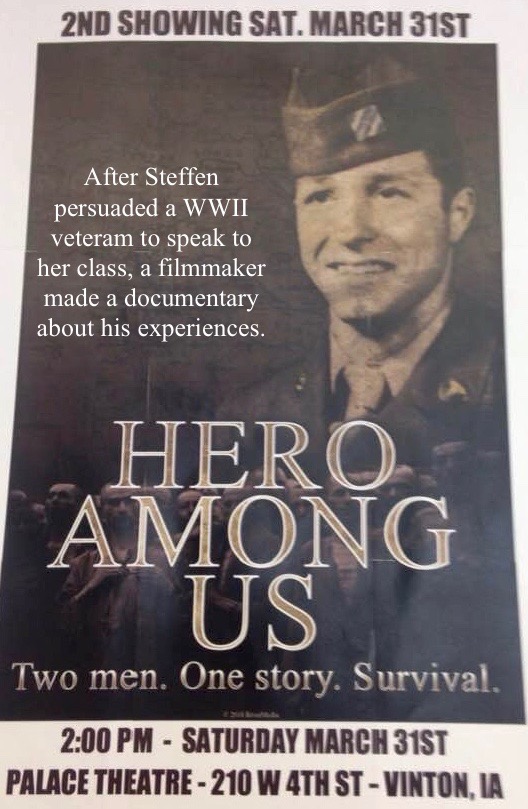

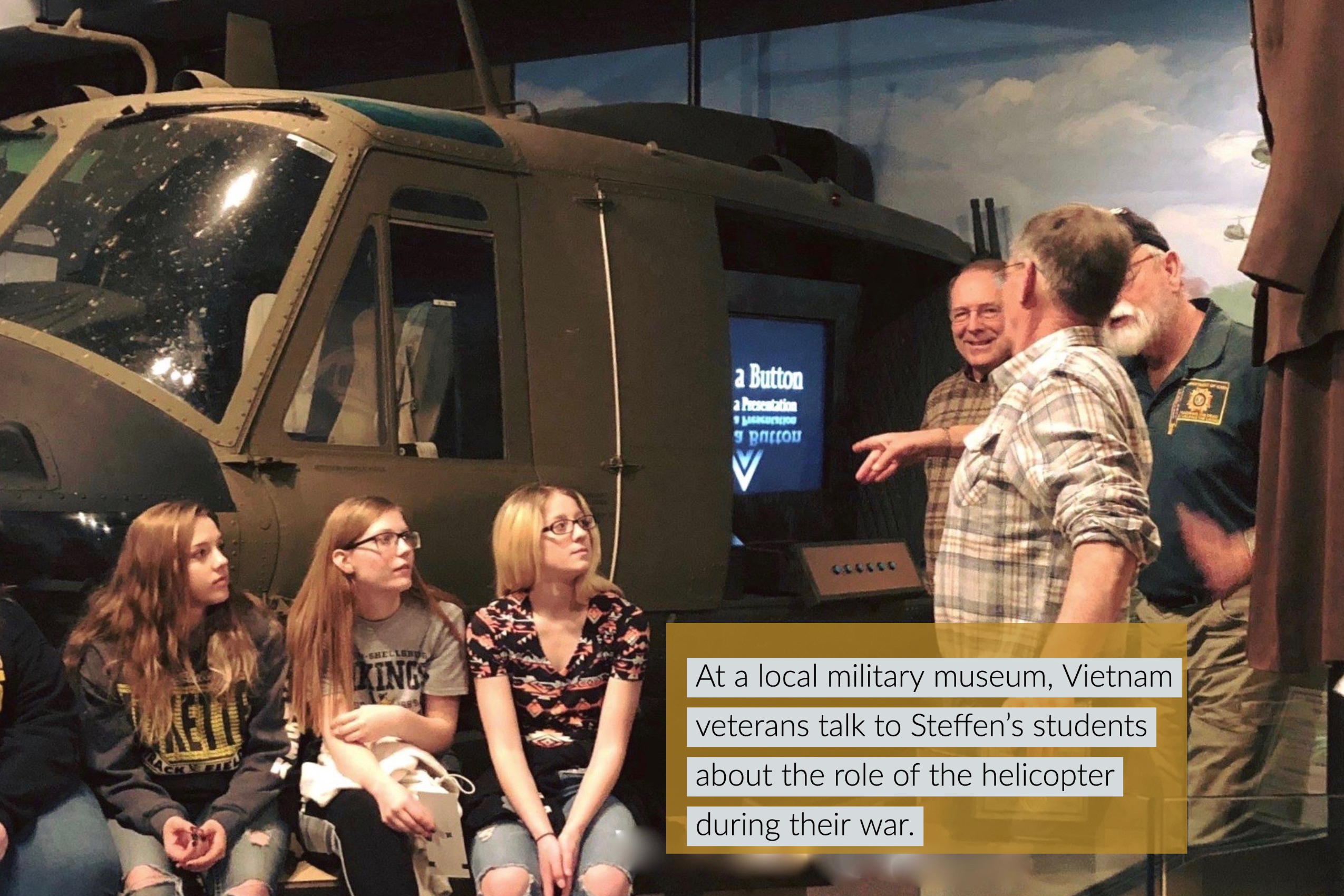

Steffen invites adults who care about history and education to tour the exhibits: “school administrators, the district superintendent, school board members, former students, and a group of local veterans who regularly visit my classroom.” This last group includes many Vietnam veterans who share their experiences and answer student questions. Steffen has recruited a large group of veterans willing to speak with students, and “typically about ten to fifteen of them” visit the Cold War museum.

Steffen invites adults who care about history and education to tour the exhibits: “school administrators, the district superintendent, school board members, former students, and a group of local veterans who regularly visit my classroom.” This last group includes many Vietnam veterans who share their experiences and answer student questions. Steffen has recruited a large group of veterans willing to speak with students, and “typically about ten to fifteen of them” visit the Cold War museum.

Students stand by their exhibits, ready to describe their research to those who stop by. “This allows the students to feel they are experts on the topic” and to practice the all-important art of “self-presentation.” Steffen reminds her sophomores that many of those visiting serve on local scholarship committees. An excellent exhibit may be remembered two years later, when a student is applying to college.

Some students impress visitors less with their exhibit design than with their knowledge and interest. “Not every student is good at presenting their topic visually. I might think a student hasn’t put much effort into his project; then a visitor tells me about all the student had to say. This shows me the project is working. If the student enjoyed it enough to impress someone three times his age, he’ll hopefully remember it beyond this year.”

Older adults visiting the museum bring to it their own memories of the Cold War. Students who’ve worked on the nuclear arms build-up will later tell Steffen that “some of my visitors remembered doing duck and cover drills in school!” or that a visitor’s “family had built their own fall-out shelter.”

Students may learn from the inter-generational conversation that they are beneficiaries of social progress. “One pair of students designed an exhibit on the societal expectations for women during the Cold War. As part of their research, they interviewed teachers in the school district nearing retirement, including our district superintendent. These women remembered a time when physical education classes were segregated by gender and there were no girls’ sports. The kids were blown away by that,” Steffen recalls.

Considering American History from a Local Perspective

The Gilder Lehrman award application also asked Steffen to submit a lesson plan. She drew on the capstone work that completed her MAHG degree. Particularly interested in the Civil Rights movement, Steffen is curious about patterns of discrimination in her own area of the country that needed reforming. She developed a lesson on the local history of race relations.

The Gilder Lehrman award application also asked Steffen to submit a lesson plan. She drew on the capstone work that completed her MAHG degree. Particularly interested in the Civil Rights movement, Steffen is curious about patterns of discrimination in her own area of the country that needed reforming. She developed a lesson on the local history of race relations.

At a teacher workshop, she’d heard a lecture by sociologist James Loewen, author of Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. Loewen claims to have found evidence of over 500 small towns where, during the first half of the 20th century, black Americans were denied housing either by ordinance or custom. They were also targeted with implied or overt threats, such as signs posted at the edge of town warning them not to be found within town limits after sunset. Loewen has compiled his controversial research on a website. There, he names Vinton, Iowa among towns that likely used sundown methods to preserve an all-white population.

Steffen’s lesson plan takes students to the local newspaper to talk with staff and look through microfiche archives, searching for evidence to substantiate Loewen’s claim. Students also interview older residents, probing their memories of race relations. Then they write up their findings.

When Steffen’s students tackled this project (before a schedule change eliminated the block periods that had allowed time to take students to the newspaper office), most found no evidence Vinton was a sundown town. Yet they did collect testimony of prejudice and discrimination. If students formulated a reasonable argument based on evidence, Steffen was satisfied. Her students had practiced the investigative and analysis skills used by historians. At the same time, they’d seen that the evidence we find in primary sources—like the information in newspapers today—may be inconclusive or incomplete.

Primary Source Analysis Builds Critical Thinking Skills

Prior to visits from veterans, Steffen tells students, “You get to ask the questions you want to ask. They’ll decide what they want to reveal to you. What they tell you may not be the whole truth—it may be what they think you can handle, or what they are willing to share. Does that mean we take their account as the be-all and end-all on the war, or even that sector of the war? No, we have to compare what they say with other historical sources.”

Prior to visits from veterans, Steffen tells students, “You get to ask the questions you want to ask. They’ll decide what they want to reveal to you. What they tell you may not be the whole truth—it may be what they think you can handle, or what they are willing to share. Does that mean we take their account as the be-all and end-all on the war, or even that sector of the war? No, we have to compare what they say with other historical sources.”

Projects involving first-person accounts of history push students “to think about where they can find other sources, how they can examine primary documents for credibility, and so on. Because of MAHG’s emphasis on primary documents, my students now learn these critical thinking skills,” Steffen says.

Steffen hopes her students learn that history can “help us as citizens make informed decisions today.” The tools we use to analyze history help us to analyze current politics—”to ask questions, to look at different perspectives.” But history can also inspire us. Steffen loves the Civil Rights Movement, when “ordinary people did extraordinary things.” She tells students, “If you don’t see [others offering] an answer to a problem, maybe you are the problem solver. What can you do?”