Meet Our Teachers

Lauren Fitzgerald

In March 2021, as students returned from a year of remote learning, Lauren Fitzgerald began teaching history at one of the country’s most unusual public schools: Pearl-Cohn Entertainment Magnet High School in Nashville, Tennessee. In partnership with Warner Music Group, Pearl-Cohn operates a state-of-the-art, student-run recording studio. Students study audio engineering and broadcasting, market communication, or cosmetology, while taking a core curriculum of math, English, science and history. Fitzgerald, who previously taught in middle school, was thrilled to land the job. She works with students about to launch adult lives, helping cultivate in them the skills, creativity and confidence they need.

At the same time, Fitzgerald works to build her own skills and content knowledge. She’s earning a Master’s in Curriculum and Instruction: Secondary School Instruction at Tennessee State University. She also attended a one-day online Teaching American History seminar, “African Americans After World War I.” The class so inspired her that she sent TAH Programs Coordinator Monica Moser a thank-you note.

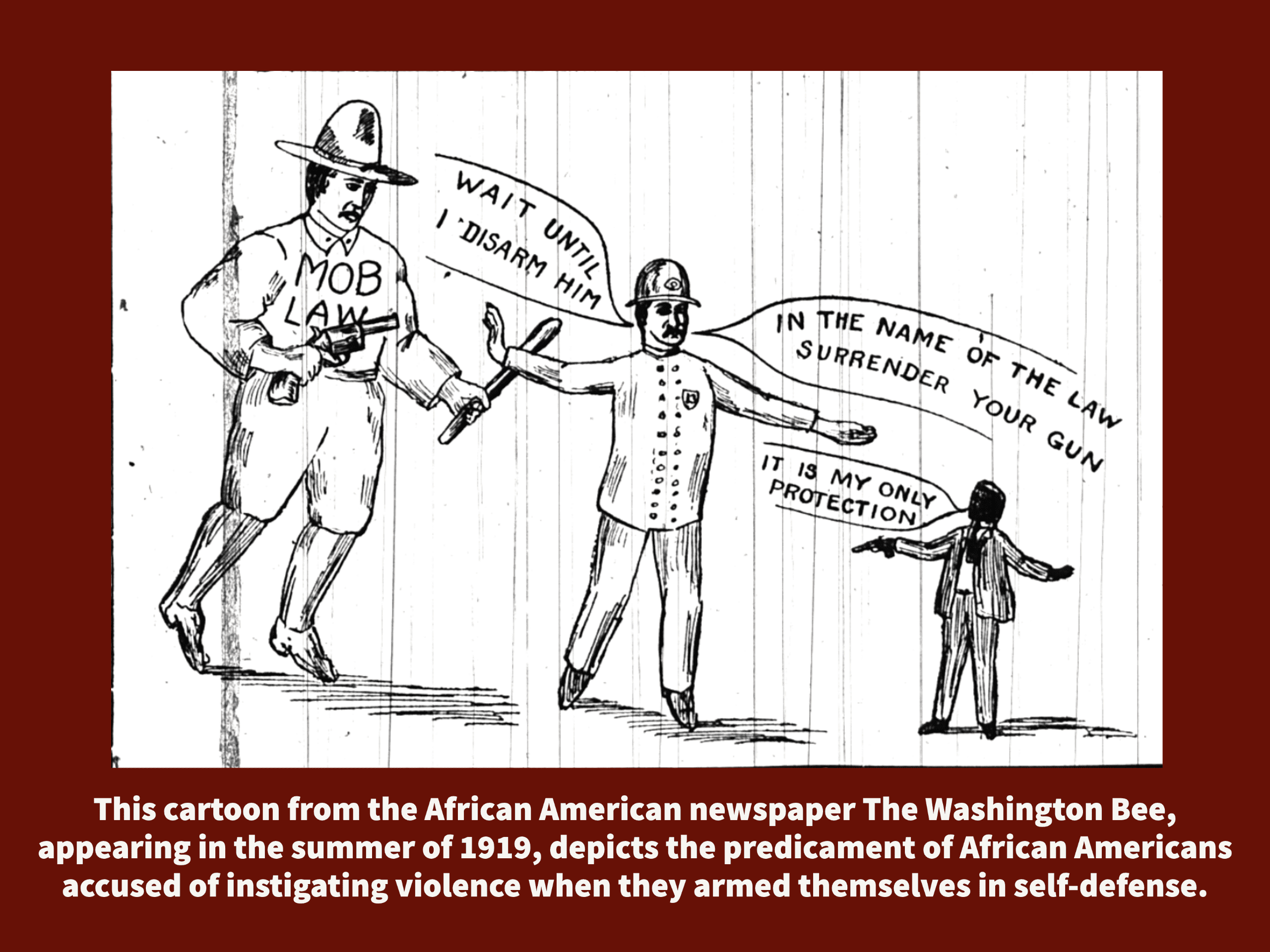

Because the seminar occurred online, TAH opened it not only to teachers in the sponsoring school district but to “teachers nationwide.” Fitzgerald met and talked with teachers she otherwise would not have met. Online TAH seminars, like those that meet in person, involve discussions facilitated by scholars. This seminar was led by Professor David Krugler, of the University of Wisconsin-Platteville. “He exceeded my expectations,” Fitzgerald said. “He is a very warm person, passionate about his material.” He dove “deep under the surface” of history to find “rarely reproduced” sources: news articles, political cartoons, photos, poems and government reports.

Racial Violence in the Wake of World War I

Such sources inform Krugler’s book 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back. It analyzes a series of mob attacks erupting in American cities and towns as veterans of World War I demobilized. Although ignited by racial hatred, the violence betrayed economic insecurities, Krugler argues.

African Americans had fought in Europe to “save the world for democracy.” Some had been assigned to French divisions and honored there for heroic front-line combat. Now they wanted to see equality realized at home. Leading African Americans like W. E. B. DuBois called for greater access to jobs and decent housing. Meanwhile, Whites returning from war to the now-crowded American industrial labor market resented competition from Black fellow-veterans.

In the South, where cotton prices rose due to war-time demand, Black sharecroppers started challenging the peonage system that kept them underpaid and in debt to plantation owners. Those planters’ profits and social status depended on this system.

African American Farmers Assert Their Rights—and Face White Backlash

Krugler shared with teachers news accounts of mob violence in Elaine, Arkansas on October 1, 1919. A group of Black farmers hired a Little Rock law firm to sue plantation owners who had not paid them for cotton they harvested the year prior. They also began organizing a farmworkers’ union. To stop the effort, the landowners “spread rumors that the farmers were organizing to kill White people,” Fitzgerald recounted. Actually, the Black sharecroppers, fearing violent resistance to their unionizing effort, had armed to protect themselves. When law enforcement officers arrived outside a church hosting a union meeting, someone—no one knows who—shot at them from the nearby woods. This led to a massacre the following day. Groups of white men, many from outside the county, began killing African Americans while law authorities arrested others, holding them until plantation owners arrived to vouch for them as tractable employees. Those not vouched for were accused of murder. Twelve were summarily convicted.

Krugler shared with teachers news accounts of mob violence in Elaine, Arkansas on October 1, 1919. A group of Black farmers hired a Little Rock law firm to sue plantation owners who had not paid them for cotton they harvested the year prior. They also began organizing a farmworkers’ union. To stop the effort, the landowners “spread rumors that the farmers were organizing to kill White people,” Fitzgerald recounted. Actually, the Black sharecroppers, fearing violent resistance to their unionizing effort, had armed to protect themselves. When law enforcement officers arrived outside a church hosting a union meeting, someone—no one knows who—shot at them from the nearby woods. This led to a massacre the following day. Groups of white men, many from outside the county, began killing African Americans while law authorities arrested others, holding them until plantation owners arrived to vouch for them as tractable employees. Those not vouched for were accused of murder. Twelve were summarily convicted.

Fitzgerald was particularly interested in a document written by Ida B. Wells, an African American journalist who traveled to Arkansas to talk with the condemned men and record their story. Wells’ reporting helped to raise funds used by the NAACP to launch a legal effort and eventually gain the men’s release.

“I will definitely be including excerpts from those documents in my courses next year,” Fitzgerald said. “I’ll also use the political cartoons; they spoke volumes.”

Historical Empathy Opens Understanding

Krugler’s way of using primary documents resonated with Fitzgerald, who sets out each year to cultivate “historical empathy” in her students. She asks students “to put yourself in the shoes” of those living in the past. “What would it be like to be there? How would I experience it if it happened to me?” She uses photos and videos to help students imagine history “with all their senses—to see it, smell it, hear it, feel it, taste it.

“For instance, when we’re studying trench warfare in World War I, I ask students to imagine being in a trench without clean water or toilets, with sores, open wounds, and trench foot, amid flies, feces, and frogs. I ask them to imagine the effects on soldiers’ minds.” Students then can understand the problems some veterans faced in readjusting to civilian life.

“For instance, when we’re studying trench warfare in World War I, I ask students to imagine being in a trench without clean water or toilets, with sores, open wounds, and trench foot, amid flies, feces, and frogs. I ask them to imagine the effects on soldiers’ minds.” Students then can understand the problems some veterans faced in readjusting to civilian life.

Fitzgerald was drawn into the study of history through anthropology. The high school she attended in Manassas, Virginia, had a highly diverse student body: “We were Black, White, Somalian, Pakistani, El Salvadorian, Japanese.” Ironically, the school was named after the Confederate hero Stonewall Jackson. “But honestly, there was more love than racism at Stonewall!” Fitzgerald said. She made friends with Somalian and Iranian students who invited her to accompany them to the Muslim Student Association. She was surprised to meet their faculty advisor: a petite Irish woman who taught anthropology and knew Arabic well enough to join the students in Muslim prayers. Fitzgerald took the teacher’s course, learning about Zora Neale Hurston’s work collecting African American folklore. “Now I wanted to be an anthropologist.” At Clark Atlanta University, realizing the profession required years of costly study, she gravitated to history and teaching.

How Culture Informs History

She emphasizes history’s social and cultural underpinnings. Each year she shows students a diagram of an iceberg, which presents only its tip above the ocean surface. Likewise, the visible events of history occur above complex layers of culture: “norms, values, morals, arts, etc.” These inform human choices.

Understanding history requires recovering realities beneath the surface of memory. Fitzgerald felt “hurt” when her alma mater changed its name to Unity Reed High; she loved Stonewall Jackson High, and besides, “I don’t think an erasure of history is the answer.” The old name kept the history of the Civil War in mind. Fitzgerald also worries about recent legislative attempts to direct how racial history is taught, lest children be taught shame for the past. “I feel it’s a little forward to say that people are not able to teach history without making it a blame game.”

Promoting Courage—And Forgiveness

Historical empathy makes room for forgiveness. Teaching school desegregation, Fitzgerald shows a clip of a 1996 Oprah show, featuring the Little Rock Nine and three of the white classmates who tormented them—or passively watched others do so—as they tried to integrate Little Rock High. “There was a very powerful conversation,” Fitzgerald said. “The tormenters said that when they were teenagers, they were just going with the flow. People were telling them at home that they shouldn’t have to go to school with Black students. They said that even when they felt their classmates’ behavior was wrong, they didn’t have the courage” to object.

Fitzgerald moved frequently during her childhood as an army brat. She lived in Arkansas and remembers it as a gentle place. In contrast with the keen observers of Nashville, who “have a high standard of excellence,” people in Arkansas “are very polite; no one is going to point out someone else’s mistakes. They live by the golden rule as much as possible.” Thinking of events in Elaine and at Little Rock High, she wonders, “How’d that even happen?”

She knows that “in history, that thread of courage is everything.” Hence, when she encourages students to live up to their potential, she tells them to act according to their own inner moral standard. “I want them to have self-respect,” she says. “I tell them, ‘It doesn’t matter what I think” or what others think; “you need to be able to walk away from whatever you did and respect yourself.” She hopes they understand themselves as actors in history, whose choices shape our future.

Before beginning her new teaching position at Pearl Cohn High School, Fitzgerald participated in a video made by Cedric Caldwell (the faculty advisor to Relentless Entertainment, Pearl Cohn’s student-run recording studio). Caldwell asked faculty and staff of the school to lip-synch to the CeCe Wynan’s song “Come On Back Home,” then blended these performances to welcome students back to the high school when in-person classes resumed in March 2021.

You can also watch a Nashville news report on the “Welcome Home” video.