Meet Our Teachers

Lauren Goepfert

The Lasting Impact of a Weekend Colloquium on the Founding

Lauren Goepfert carries her Ashbrook pocket Constitution with her at all times. Hence she’s had it signed by legal experts and famous activists she’s met at professional development programs for teachers. Last summer, as a new Madison Fellow doing the required coursework at the Georgetown Summer Institute, Goepfert got Mary Beth Tinker to put her signature next to the First Amendment (When Tinker and her brother wore black armbands at school during the Vietnam War, they were suspended, leading to a landmark 1969 free speech case). But for Goepfert, the Constitution booklet is not merely a history geek’s souvenir.

What Can You Do with a Pocket Constitution?

In early October, as she taught the Constitutional Convention in her 11th grade US history classes at Longwood High School in Middle Island, New York, Goepfert gave each student their own Constitution booklet. “But what can you do with it?” one student asked. “What can I not do with it?” she responded.

As her students worked their way into the history of the early republic, Goepfert repeatedly referred them to the Constitution, their guidebook to unfolding political developments. In Mid-November, Goepfert’s department chair observed her class as she taught McCollough v. Maryland, an early (1819) test of the supremacy clause (Article VI, Section 2). First she explained the context of the ruling: that in 1818 the State of Maryland had attempted to tax the Maryland branch of the Bank of the United States, newly created by Congress, and branch head James McCullough sued. She handed out an excerpt of the opinion in the case, written for a unanimous Court by Chief Justice John Marshall. Marshall wrote that “the power to tax is the power to destroy,” and that a state could not inhibit a federally created institution. Then Goepfert said, “‘Let’s go to Article VI.’ And all my students went to Article VI. My department chair was really impressed.” Goepfert’s students had already learned their way around the Constitution.

The Weekend Colloquium That Changed Everything

Goepfert did not begin unlocking the many ways the Constitution illuminates other documents in American history until, while teaching in Florida, she learned from colleagues about Teaching American History seminars. She’d always loved history—her history-loving (he was a guidance counselor) father instilled that in her—“but I had no idea there were other programs I could do.”

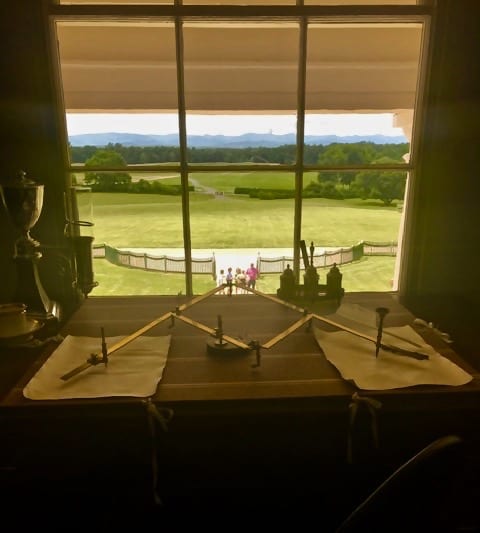

That summer she attended a TAH weekend colloquium in Montpelier. “I couldn’t believe I was staying at James Madison’s house, standing on his grounds, looking at places he saw everyday. To look out the same window he looked out of when he was in his library, studying for the Constitutional Convention!” She took a photo of the view and keeps it on her desk at school. To curious students, she explains where she took it and says it reminds her that “anything is possible, as long as you put the work in.”

Professor Gordon Lloyd led the discussions during the weekend in Montpelier. (An expert on the Constitutional Convention, Lloyd has authored several TAH core document collections on the founding, along with interactive exhibits hosted on the TAH website.) At first, Goepfert was hesitant to jump into the conversation. Then Lloyd responded warmly to a question she posed, later telling her, “You should have more confidence. You have good ideas to contribute.” It was all the encouragement she needed to dive in deeper.

“I’d never had discussions like that before. And ever since then, it’s all I’ve wanted to do, to talk to someone about history like that,” Goepfert says.

Becoming a TAH Regular

She became a regular participant in one-day TAH seminars in Palm Beach County. She looked into the MAHG program. “I knew from the TAH seminars that the classes in this Masters program would be so much fun,” she said. At the close of a seminar on [Lincoln’s Writing and Speeches] with Professor Lucas Morel, she told him, “I am applying for a Madison fellowship, and I hope I get it, so I can take classes with you!”

In 2018, she did win the fellowship. She has completed three of TAH’s interactive online courses, finding the discussions that occur in them as stimulating as those at other TAH programs. Now she looks forward to her first summer residential courses. She’ll room in Ashland with a friend from Wyoming she made at last summer’s Georgetown Summer Institute. “The first day, we hit off, becoming best friends forever.” Soon Goepfert was convincing her new friend to transfer into the MAHG program. “The professors are awesome,” Goepfert advised her friend. “The discussion—that’s my favorite part. Talking with other people who are like you, building off of each other’s comments. Connecting to other teachers who share your passion—it’s like getting another family.”

Students Remember What They Learn from Primary Documents

As she feeds her own growing curiosity about American history, Goepfert works to build that of her students. Adopting TAH programs as a model, she has changed her teaching approach. Before, she brought to class only a few iconic primary documents older teachers suggested she use. Mostly, she told students America’s story. Now she helps students tease out the story for themselves. She brings in documents she’s studied in TAH seminars.

“There are so many documents out there, so many texts we can use in the classroom, so that class is not just me telling them the key points to remember.” Of course, it takes time for students to learn the necessary skills. “I teach two sections of US history in a humanities block schedule shared with an English teacher (my humanities block is with the Global II). So students are learning writing and reading skills as they learn history. During the first half of the year I’m helping students analyze the documents. I show them how to annotate them, we talk about them, and they write about them. I don’t expect deep conversations at first, but by March or April they will be ready for that.”

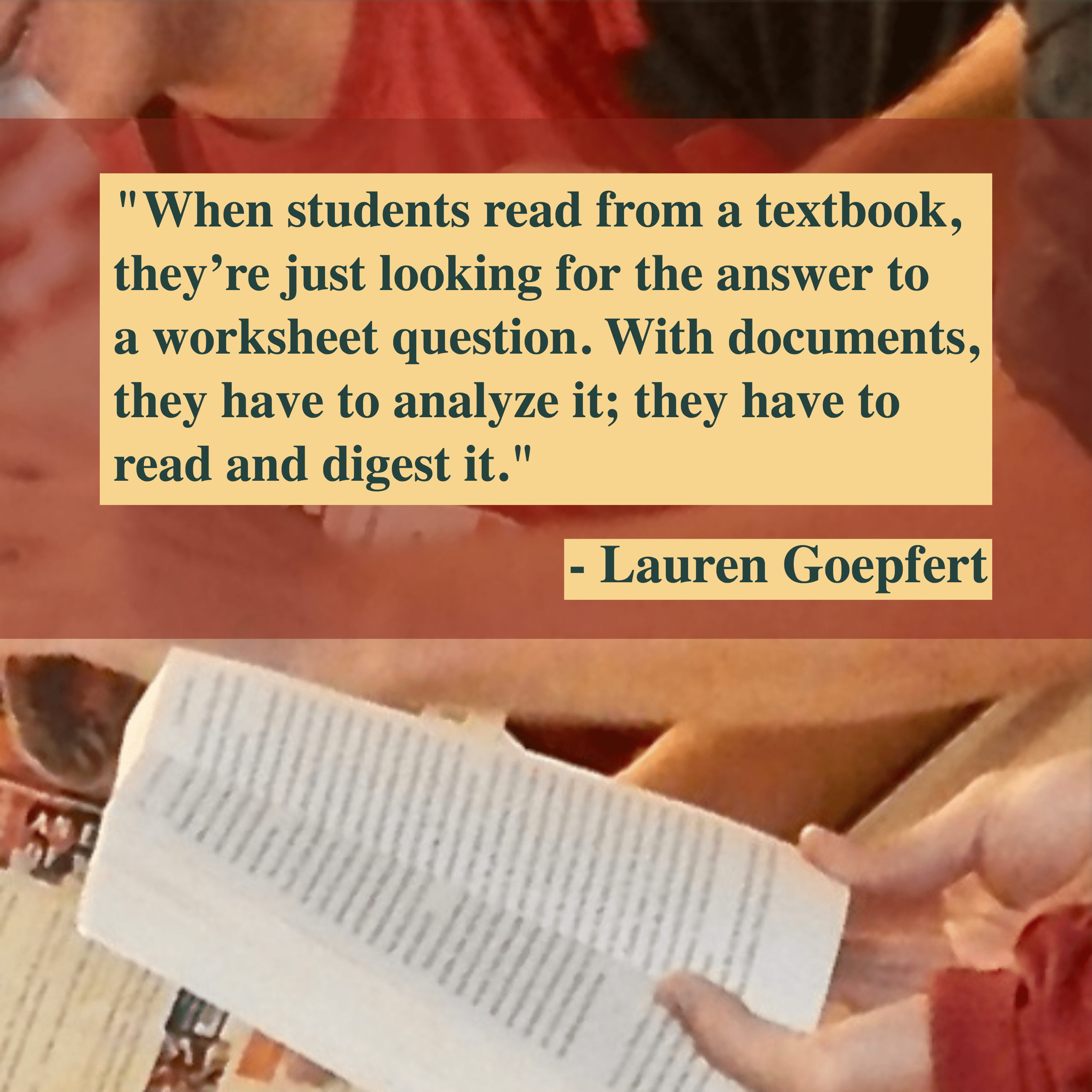

Her students “feel they are getting the scoop on history—not hearing the story secondhand, but rather from the people who lived during the era.” Knowledge gained this way is longer retained. “When students read from a textbook, they’re just looking for the answer to a worksheet question. With documents it’s more of an analysis, and there is no clear-cut answer written out for them in the text. They have to analyze it, they have to read and digest it. They can’t just spit it back.”

Appreciating the Complexity of Democracy

Students also better understand the complexity of democracy. Sustaining our form of government requires thought about many areas of social and political life. Goepfert mentioned Washington’s Farewell Address. “When I began teaching, I told students what I’d been told: that Washington warned Americans to ‘Avoid political parties and foreign entanglements.’ When you really study the Address, there is so much more! He talks about education, about what it is to be an American, about religion and religious freedom. It’s a shame that a generation of people think it’s just the two things I learned as a student.

“I feel I can’t do enough to learn more, teach more—to go out and find history in the documents and bring it back.” She also feels a “duty to spread the word to teachers” about opportunities to build content knowledge and improve their teaching effectiveness through primary document study. She has presented her teaching approach in professional development programs and serves on the Teacher Advisory Board for the National Constitution Center. Of TAH, she says, “If a beginning teacher participates in this program, it could really change the track of their career.”

Meanwhile, she’s eager to see how much of a difference her new experiment with the pocket Constitution will make to student learning. At each new stage of American political development, her students will consider “how is the government allowed to do this? What part of the Constitution permits it?” She’ll be learning at the same time: “Because I taught eighth grade in Florida for many years”—the course covered Discovery and Settlement to Reconstruction—“I know most about the pre-20th century past. I’m excited that in MAHG I’ll take courses like Modern America and the Presidency from Andrew Johnston to Obama.”

Meanwhile, she’s eager to see how much of a difference her new experiment with the pocket Constitution will make to student learning. At each new stage of American political development, her students will consider “how is the government allowed to do this? What part of the Constitution permits it?” She’ll be learning at the same time: “Because I taught eighth grade in Florida for many years”—the course covered Discovery and Settlement to Reconstruction—“I know most about the pre-20th century past. I’m excited that in MAHG I’ll take courses like Modern America and the Presidency from Andrew Johnston to Obama.”

As a social studies teacher, Goepfert believes she performs a critical role in sustaining our democracy. She wants students to understand that government “functions on the consent of the governed,” and that in the United States, citizens must register their consent through Constitutionally prescribed procedures. “There’s a lot going on in current politics. To understand what is happening, students need to know what’s in the Constitution and how it has been interpreted over the years,” she says. An athlete in college, Goepfert uses a sports analogy. “If you’re going to play the game, you need to know the rules. It’s not about what you think government should do. It’s about what the Constitution allows.”