Teaching the Blessings of Liberty

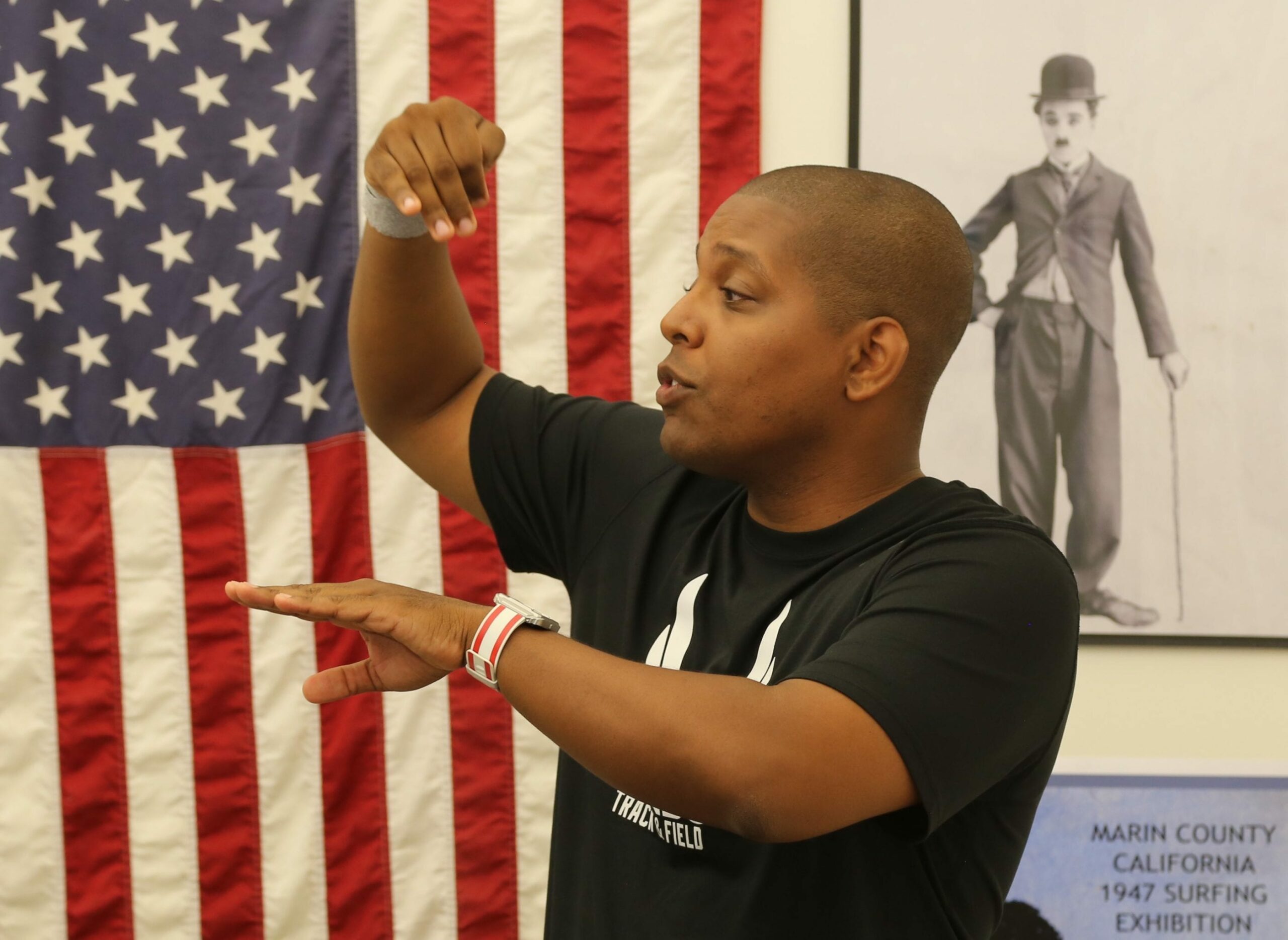

Malik Ali won a Chairman’s Award in December 2017 for his outstanding performance on the final exam in Ashland University’s Master of American History and Government (MAHG) program. Ali’s command of his subject is matched by his effectiveness in teaching it. He has taught for twelve years at The Branson School, a highly respected private high school in Marin County, California. “Malik is a truly gifted teacher of history,” says Head of School Christina Mazzola. “He challenges our students to think deeply and examine issues from many diverse angles. He urges them out of their comfort zones with his unique style of engaging them with stories, rather than dates and facts.”

Yet teaching history was not Ali’s first career goal.

A Love of Autobiography Leads to History

Ali majored in English at Morehouse College in Atlanta, where he nourished an interest in the great American autobiographies. At Branson, he first taught English, and saw students grow especially engaged as they read excerpts of such works as Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography and Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Other writings by real persons of the past—such as Abraham Lincoln’s sober reflection on the meaning of the Civil War in his Second Inaugural Address, and the Letter from Birmingham Jail that Martin Luther King addressed to local pastors critical of his civil rights activism—captured their imaginations. When Branson’s academic dean asked Ali to teach American history while furthering his education in the subject, the move made sense.

As he began teaching history, colleagues at Branson showed Ali the Teaching American History website. Here he found links to the MAHG program, which presents US history and government through the lens of primary sources—the speeches, essays, letters, and other works written by earlier Americans that his students found fascinating. It was the ideal window into history for an English major who loved wrestling with words.

Moreover, “the schedule worked,” said Ali, whose school days, like those of many teachers, are extended by extracurricular duties (Ali coaches track). Through MAHG, “I could accomplish a lot in the summers,” he said. A grant from the James Madison Fellowship program supported Ali’s pursuit of his Master’s. Competition for the fellowship is keen in California, since the Madison Foundation awards only one per state each year.

His first week in the residential program surprised him with its packed schedule: three 90-minute seminars a day, each requiring 60 to 90 pages of reading. The course covered the Founding, and required “jumping right into James Madison’s Notes” (the Virginia statesman’s meticulous record of daily debate during the Constitutional Convention, rendered in long periodic sentences using archaic words like “animadvert” instead of “criticize.”) But soon Ali was enjoying the pace. “I like challenges,” he says.

Reclaiming a Birthright and Discovering a Theme

He was also reclaiming the feeling he had as a child growing up in Philadelphia—“that the Revolution and Founding are my birthright.” His school field trips had taken him to historical sites where he soaked up all the guides said. As a high school student he’d worked in a cheesesteak shop on Germantown Avenue, very near the site of a famous battle in the Revolution. He walked everywhere, stopping to read all the historical plaques. “When I go home now, I ask one of my cousins or friends to take a day and visit the museums with me.”

This, he says, “is a very tribal way of understanding history. I’m more sophisticated now.” Ali’s MAHG study has deepened and informed his lifelong fascination with America’s momentous experiment in self-government. It has also given his US history course a central theme. Throughout the school year, Ali reminds his students of a key phrase from the Constitution’s Preamble: “the blessings of liberty.”

“Liberty is an abstract concept,” Ali explains. “You only know it through the opportunities it creates in your life. Many of these are granted us in the Bill of Rights: liberty of conscience, freedom of assembly, security in your own home, the ability to pursue education and acquire and dispose of property as you will. Those are the things that a free society should afford you. As the Preamble states, they are blessings ‘to secure . . . for ourselves and our posterity’—to pass on to the next generation.”

Yet before articulating these rights, the Founders had to design a framework of government that balanced their competing ideas of self-government. In the Articles of Confederation—the first plan of government, devised during the Revolution—“liberty is emphasized, but not the fact that it is a blessing. When you have a lot of people saying, ‘My liberty! My liberty!’ one group’s liberties start infringing on those of others.”

Ali asks students to consider the situation in the US just after the Revolution. In Massachusetts, veterans of the war who were losing their farms due to high mortgage interest rates launched an armed rebellion. Elsewhere, state legislatures balked at paying war debts or tried to unilaterally levy tariffs. Students begin to understand the urgency felt by delegates to the Constitutional Convention, who realized their hard-won liberty could be unraveled by internal disorders.

“Now we’re studying post-Civil War Reconstruction,” Ali continues. “Students are seeing that in that moment of history, the rights that should be the blessings of liberty for the black folk were considered criminal behavior” by Southerners who feared empowering former slaves. “So if they don’t understand the Preamble the first time we study it, they get it the second time, or they get it when it comes up a third time.”

Teaching the Constitution as Enduring Framework and Ongoing Challenge

Ali helps students understand the Constitution “as the groundwork for a resilient political culture that has withstood some profound stress tests.” He wants them to understand that the document was forged through “compromise—through reflection, conversation, persuasion, and choice. They need to appreciate that when ratified, it was an imperfect document, and a great deal of American experience has been a process of revisiting the document and making it as true as possible to the ideals presented in the Preamble.”

The MAHG program helped Ali reach this understanding of his purpose as a teacher of American history and government. Central to the process were countless in-depth conversations about primary documents with other dedicated teachers in the program. These colleagues—spread across the country—are still helping Ali perfect his teaching strategy. “I correspond with them every week to get ideas,” he says. “I came into the program not new to the classroom, but new to social studies. Over the course of four summers I gained so much confidence and fluency that now I’m prepared for almost any question my students can throw at me. Even if I don’t know the answer, I can say, I’ll read about it and ask a colleague and get back to you tomorrow.”

Ali’s sense of mission expanded in conversation with these teaching colleagues. “If you were to meet the teachers I’ve met in MAHG, you’d see the gifts they have—the passion, the deep knowledge, the communication skills. You know these people’s classrooms are in good shape. We need more classrooms like that,” Ali says.