Meet Our Teachers

Marc Turner

Illuminating the Civil Rights Movement in South Carolina

As soon as he learned that he could write a capstone project as the culminating work for his Master of Arts in American History and Government degree, Marc Turner knew the theme he’d pursue. He would explore some of the uncelebrated heroes of the twentieth century Civil Rights Movement in his adopted state, South Carolina.

Turner, who grew up in Oregon, has taught in South Carolina for 29 years. Currently he teaches at Spring Hill High School. It’s a magnet school in Chapin, a suburb of Columbia, the state capital. Turner has devoted many spare hours to exploring “the South Carolina universe,” drawing his own children into his quest. (They still rib him for having roused them from bed and packed them into a van one long-ago spring break morning, so as to drive them 90 miles to the Revolutionary War battlefield at Cowpens.)

A Rich Archive of Local History

In 2017, Turner worked as a Master Teacher in the Summer Teacher Institute of the University of South Carolina Center for Civil Rights History and Research. Teachers who participated learned little-known stories from local civil rights history, meeting many of the key activists in the era’s student-led protests. In 2019, the center opened an exhibit called “Justice for All,” a rich collection of written and visual documents by and about leaders and activists in the state’s civil rights struggle. After the document collection was digitized and a traveling version of the exhibit was produced, Turner began thinking about how he might help make the resources in this exhibit more accessible to secondary school teachers. He wanted to help the center teach young South Carolinians how activists from their own state helped to propel civil rights gains across the South.

For his capstone, Turner developed ten lesson plans on these activists’ work, using primary documents from the center’s exhibit that he carefully curated. The lessons span an era beginning in the late 1940s and culminating in 1983, when one leading activist, I. DeQuincey Newman, was elected to the South Carolina State Senate. They illuminate some of the groundwork that made the civil rights gains of the 1960s possible, while pointing toward goals that later activists would continue to push. Turner provided each lesson plan with questions to guide students’ inquiry. He also wrote formative and summative assessments, so that students completing the lessons would realize what they had learned.

Local Heroes Who Prompted Change Across the South

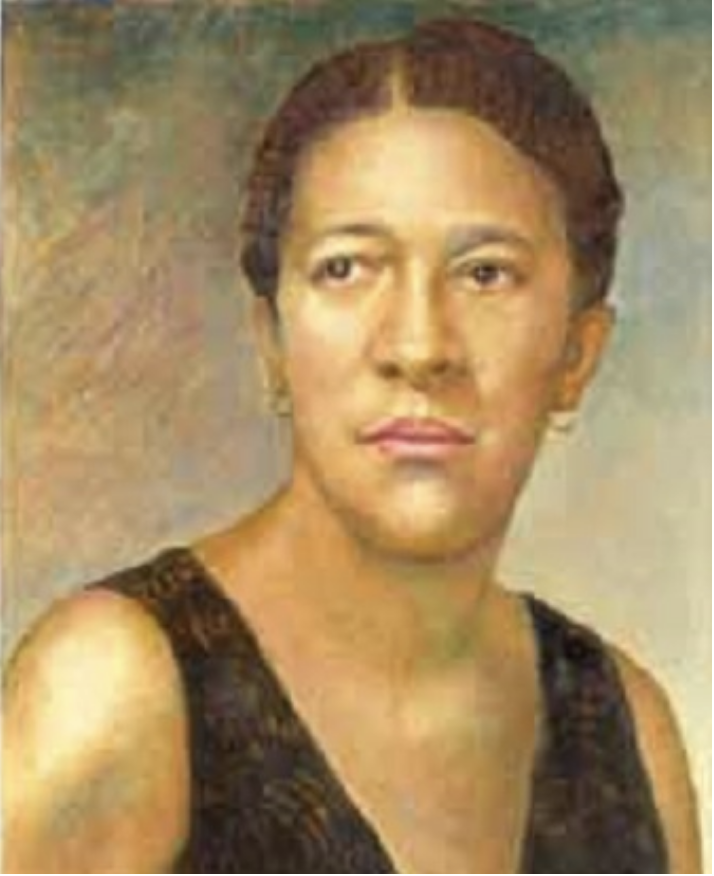

Professor David Krugler, faculty advisor to Turner as he worked on the capstone, praised Turner’s attention to the “ordinary heroes” involved in these cases: “activists and pioneers whose names and deeds are, still today, unheralded or overlooked in lessons on civil rights history.” For example, Turner excerpted a number of documents written by Modjeska Monteith Simkins. She began her career in 1921, as a school teacher at the largest of Columbia’s African American high schools, then became South Carolina’s only fulltime, statewide African American public health worker, as Director of Negro Work for the South Carolina Tuberculosis Association. Fired from this job after her election as Secretary of the State Conference of the NAACP, she redoubled her activism. “In 1944, she helped mount a successful court challenge to South Carolina’s law protecting white-only primaries,” Krugler recounted. “The resulting case, Elmore v. Rice, provided a foundation for subsequent decisions that led to the famous Brown v. Board of Education decision.”

Simkins “had her hands in everything” that civil rights advocates of the mid-twentieth century accomplished, Turner said. Still, Simkins’ efforts were effective only through the work and endurance of others. One of her allies in the South Carolina civil rights movement was the Reverend Joseph A. DeLaine, president of the Clarendon County chapter of the NAACP. DeLaine helped to mount a suit challenging school segregation in the county. This suit was eventually bundled along with four others into the case the Supreme Court deliberated in Brown.

Poring through the voluminous records left by DeLaine and Simkins, Turner uncovered stories of ordinary people who sacrificed peace and privacy for the civil rights cause. A soft-spoken domestic worker in Columbia, Sarah Mae Fleming, protested the segregation of public transportation in South Carolina after being abused by a bus driver. He berated her after she took the seat of a white woman exiting a city bus. Seeking to defuse the situation by disembarking, Fleming pulled the cord requesting the driver to stop. The driver stopped, then punched her. Afterwards, Fleming allowed Modjeska Simkins to file a suit on her behalf against the bus company.

Brought just after the Brown decision and just before the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the suit was dismissed at the local level, then appealed to the Federal Fourth Circuit Court. The federal court found that, given that the “separate but equal” doctrine was “no longer the law of the land” with regard to public schools, it could not be the law in public transportation, either. The circuit court remanded the case to the local court, who held the trial as instructed, yet defiantly ruled against Fleming. Still, the Fourth Circuit ruling strengthened the argument made by those who eventually negotiated desegregation of the buses in Montgomery and elsewhere in the South.

“Each of the ten lessons plumbs the rich history of South Carolina to focus student attention on primary sources that never made it into textbooks,” Professor Krugler said of Turner’s work. “I hope the lessons find their way to classrooms not just in South Carolina but also across the country—each lesson has national resonance and relevance.”

Correcting a Common Misunderstanding

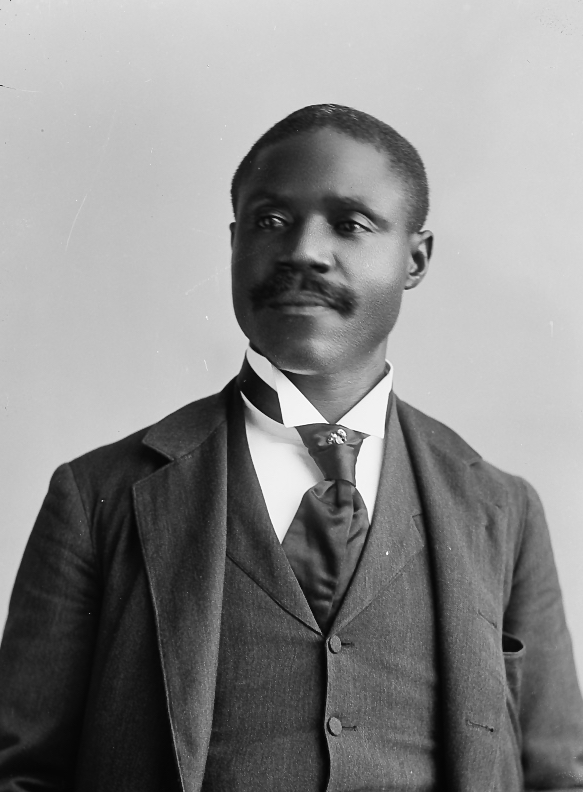

Making this history known not only does justice to forgotten leaders; it corrects a too-common misunderstanding of American history, Turner said. “If you assume that the Civil Rights Movement suddenly erupted from the Brown decision in 1954, you miss all of the work that had been done before, in both good times and bad.” He recalled his astonishment at a discovery he made thirty years ago, while working on an earlier Master’s degree in history education: the story of Congressman George Washington Murray. Born a slave in 1853, Murray served as the only black member in the 53rd and 54th Congresses, from 1893 to 1897.

“This did not compute with me!” Turner recalled. “I had learned that Reconstruction ended in 1877 and that the world came to an end for African Americans, until the 1950s. Now I discovered that a narrow space, in which the possibilities of a biracial political system had not completely evaporated, remained in South Carolina until the 1890s.” Murray, despite his lack of primary education, had earned a degree at the state normal college and worked as a farmer, teacher, lecturer, and inventor, obtaining eight patents for farming tools. He overcame a corrupt elections process to win a Congressional seat in a majority-black district. In Congress, he joined the populist fight for currency reforms and fought a bill to remove federal marshals and impartial elections officials from southern polling places, submitting voluminous testimony of elections fraud.

“That’s one of the great parts of the American narrative. Even when things get really, really tough, somebody is still fighting the fight,” Turner said. “Even though South Carolina, in 1895, adopted a new Constitution effectively disenfranchising black citizens; despite the race riots and lynching that occurred; despite the Supreme Court’s Plessy decision—you find evidence of optimism, of African Americans still believing they could work within the political system. Lots of people felt that they could make something even out of the worst-case scenario.

“History textbooks are silent on these matters, largely because there’s just so much going on, and they have only so many pages. The challenge we face as US history teachers is to tell the story in a way that gives voice to those who really believed in what our political system could offer them—in the rights our Constitution guarantees.” Studying the struggles to guarantee civil rights not only for African Americans but also for women, Native Americans, immigrants, and others helps students see the ongoing “tension in our history” between those who seek power to serve only themselves and those “who want to be part of an inclusive, diverse democracy,” Turner said. “This is what we mean by ‘e pluribus unum.’ Americans are constantly revisiting their idea of the natural rights of all citizens.”