Meet Our Teachers

Pamela Cummings

Pamela Cummings, a graduate of the Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) program, is 2023 “Arkansas History Teacher of the Year.” The award, given by the Gilder Lehrman Foundation, honors teachers who have demonstrated exceptionally creative and thoughtful teaching practices. Cummings teaches honors and general-level US History at Benton High School, in a suburb of Little Rock. She is the 2018 Madison Fellow for Arkansas. Below, Cummings talks about her teaching goals and how MAHG elevated her effectiveness.

One thing I loved about the MAHG program is that we almost never discussed pedagogy. I have a master’s degree in education. On paper, it looks really good. Completing it helped me earn better pay. But it was the easiest thing I’ve ever done in my life. The usual education workshop frustrates me, because it doesn’t teach what I need to know. What is going to help a history or government teacher the most? It’s to learn the content. The better you understand your content area, the better you will teach to your students. When I teach Progressivism—which is officially the first unit of my history course—I don’t teach all the progressive political theory I learned in MAHG, but I’m glad I studied that. It helps me explain the events that happened.

I particularly appreciated the set-up of the online program. Other online programs tell you to read something or watch a video and then write a paper. I need the accountability that comes with participating in a live, interactive conversation. I learned a lot from MAHG’s professors; they’re top-notch. I also learned from my fellow teachers studying in the program. Before coming to the seminar session, they had read the assigned material; they had been thinking about it all week. That deepened the conversation.

My Teaching Style

I suppose my own teaching style resembles that used in MAHG. I didn’t really think about this until about the time I finished my MAHG degree. It was a student in one of my classes who pointed it out.

“I need some help,” the student said. “Would you do that thing you do?”

Confused, I responded, “What thing that I do?”

“You ask me a bunch of questions,” she replied.

Well, that is the way I teach. Instead of answering students’ questions for them, I push them to find the answer. I’ll ask a kid as many questions as it takes to get them there.

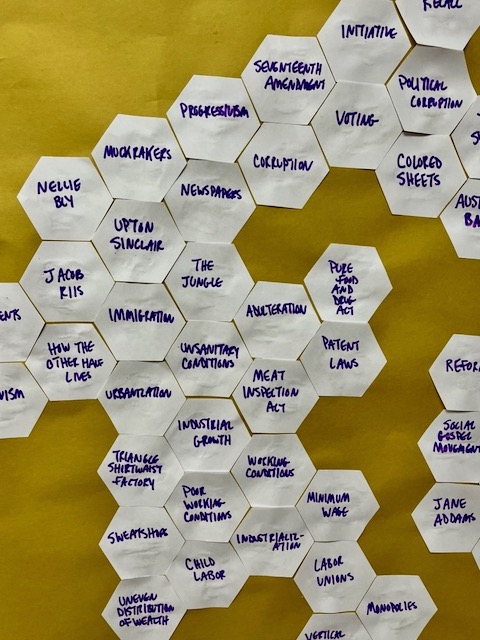

I’ve been using a teaching strategy called “hexagonal thinking” in the first unit of my history course, which begins in 1890. We’re studying some of the leading Progressive journalists and political leaders, and the problems they were discussing. I divided the class into groups, and gave each group a pile of hexagonally shaped pieces of paper on which I’d written the names of people, social problems, significant events, and policy proposals of the Progressive Era. Students were to arrange the hexagons like tiles, with each tile touching up to 6 others. I walked around the room, asking students to explain how the words on tiles that touched each other represented related issues. I’d ask questions like, “Why did you put “Jacob Riis” (he was a photographer who documented conditions in the slums where immigrants lived) next to The Jungle (that was a novel that described conditions in the meat-packing industry)? “You may give me an answer, but if I see that look in your eye that tells me you’re not sure, I’m gonna ask more questions,” I said. “I want you to know why you think what you think.”

Students Appreciate Being Pushed to Think

Students think I’m a hard teacher. But over time they realize I do care. They appreciate being pushed to figure things out—and, learning in this way, they generally remember what they learn.

We work hard in my class. We don’t do a whole lot of homework. I know the kids won’t do it. They will do the work for English or math or science before the work for history. They sense, from all their other experiences in school, that the STEM classes are more important than social studies. They are required to take only one semester of US history, and the scope of that course is very restricted. It begins in 1890 and goes up to the present day. Next year, the course will cover even less: it will begin with the 1929 stock market crash and continue to the present. Students also do not need to pass a standardized test in history or government in order to graduate. It is true that they must pass a citizenship test similar to the one administered to those immigrants seeking naturalization. But the test is not difficult. If they miss a question, the next slide gives them a hint of the correct answer, then they get the question they missed right back again. If they simply pay attention to the test process, they pass.

So, I tell students on the first day that my class will not be easy. I show them a video of a deep-sea diver; it includes a conversation in which he is asked, “What do you enjoy about your work?” He responds, “I don’t understand the question. Are you asking me if my work is fun? I do this work to learn things I cannot learn in any other way.” Then I read students the portion of John F. Kennedy’s speech at Rice University in which he challenges Americans to go to the moon. He says, we’ll do hard things, because we want to win! I tell them by going through my class, they will win! They leave that first class period thinking, “Oh, my goodness, what did I get myself into?”

Why Young Citizens Need to Study History

Our unit on the progressives includes the beginning of compulsory public education. So I give them a little speech. I say, “You might not want to be here right now. But you are, and here’s why: you are here so that all of your classmates will be here. One day you all will be running the businesses we depend on; your generation will be running for office; you’ll be the decision-makers. You want to make sure that all your classmates will make good decisions. You will learn about decision-making together by studying the choices that have been made in the past.’

Before we begin the modern history course, we go over the Founding; I cover that even though it is not in the standards, because students need to understand it. I introduce the Founding Fathers by saying, “Many people dismiss certain Founding Fathers as irrelevant—typically those who were slaveholders. Listen. Every one of us has done something we should not have; none of us wants to be judged on the basis of that one issue alone. Today, none of us are slaveholders, but we are still participating in some aspect of our society that is unjust or likely to lead to problems in the future. Future generations may ask of us, ‘Why didn’t you do more to mitigate climate change? You had enough information to see what was happening. You could have done something different.’ The truth is, our failure on any one issue does not condemn us. We’re all redeemable. And the history we create as we make our choices, good or bad—all that history will matter. Future generations will learn from it.”