Meet Our Teachers

Ryan DeMarco

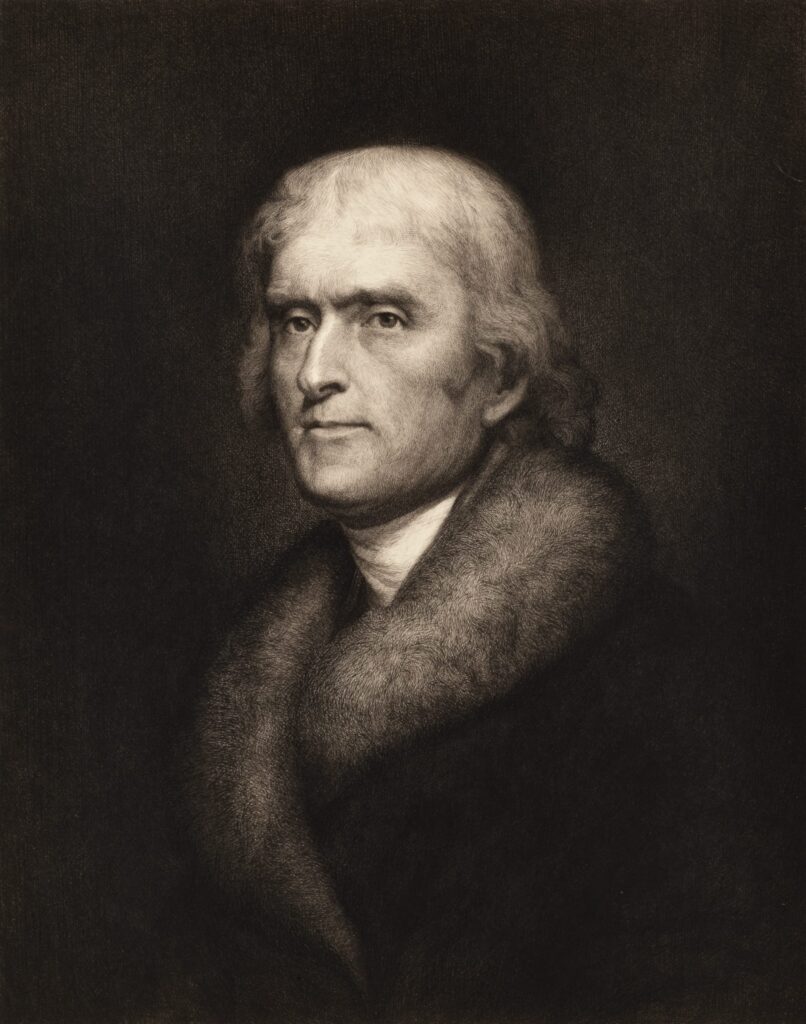

“Sometimes history teachers can lose a sense of the nuances,” says Ryan DeMarco, who teaches Advanced Placement US History and Comparative Government to 11th and 12th graders at North Cross School in Roanoke, Virginia. “Today, you hear the attitude that Thomas Jefferson was a bad guy, because he owned slaves. Well, he did, but can’t we take a deeper look before dismissing his contributions to the nation?”

Participating in an online seminar led by Cara Rogers on Thomas Jefferson, DeMarco “learned a lot about Jefferson that I didn’t know going into it.” He read writings of Jefferson he had never before encountered, while also learning facts of Jefferson’s life from Rogers, who is writing a book about Jefferson and his views on slavery. Jefferson’s thinking about slavery, and his own involvement in the practice, were much more complicated “than I ever imagined,” DeMarco concluded.

Correcting a Lesson on Jefferson and Slavery

The following Monday, DeMarco shared what he’d learned with his APUSH students. “I took 15 minutes at the start of class and said, ‘I went to a professional development on Thomas Jefferson this weekend. Let me tell you what I learned about Jefferson in relation to slavery. I hadn’t known it was illegal for Jefferson to free his slaves, due to his unpaid debts. A law passed in Virginia in the 1780’s effectively rendered Jefferson’s slaves the property of his creditors. Thus, he could not have arranged to free them upon his death even if he wanted to.’

“Telling my students about this was a moment of self-correction for me.”

DeMarco, now in his sixth year of teaching, has learned such moments of self-correction earn students’ respect. “When you share facts you’ve just learned, admitting that they altered your opinions, you model growth. You model learning.” Sharing recently acquired knowledge with students also shows students “that you care about them, and you want them to have the best information possible.”

Seminar Discussions Guided by Scholars

As an undergraduate, DeMarco specialized in Russian and German history. He went on to earn a Masters in Russian foreign policy at the University of Edinburgh. This background prepared him well for the Global Studies program he now leads at North Cross. It prepared him less well to teach APUSH. That’s why he seeks out professional development that offers “an expert’s perspective” on American history.

“I am a TAH fan!” DeMarco wrote TAH program staff, urging them to continue the online interactive seminars. They’ve brought content-focused seminars to those like him living in rural areas. They’ve put him in contact with teachers from other parts of the country. “Part of the guilty pleasure for me in these seminars is learning from the other teachers . . . . What documents do they assign? How do they talk to students about the historical issue we’re discussing? Many teachers are far more knowledgeable on American history than I am,” says DeMarco.

He finds the free TAH seminars more engaging than those offered by other well-known programs, often taught by historians with best-selling books. Those programs feature recorded lectures. “The courses are self-paced, and you’re on your own. I had to be very self-motivated to follow through on the reading.” Knowing there will be discussion during the TAH seminar, DeMarco reads the document assignments ahead of time, noting his questions about them. “I love being able to ask the professor questions and get clarification.”

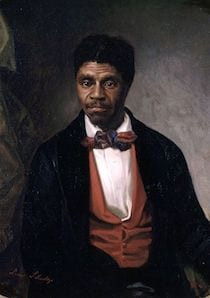

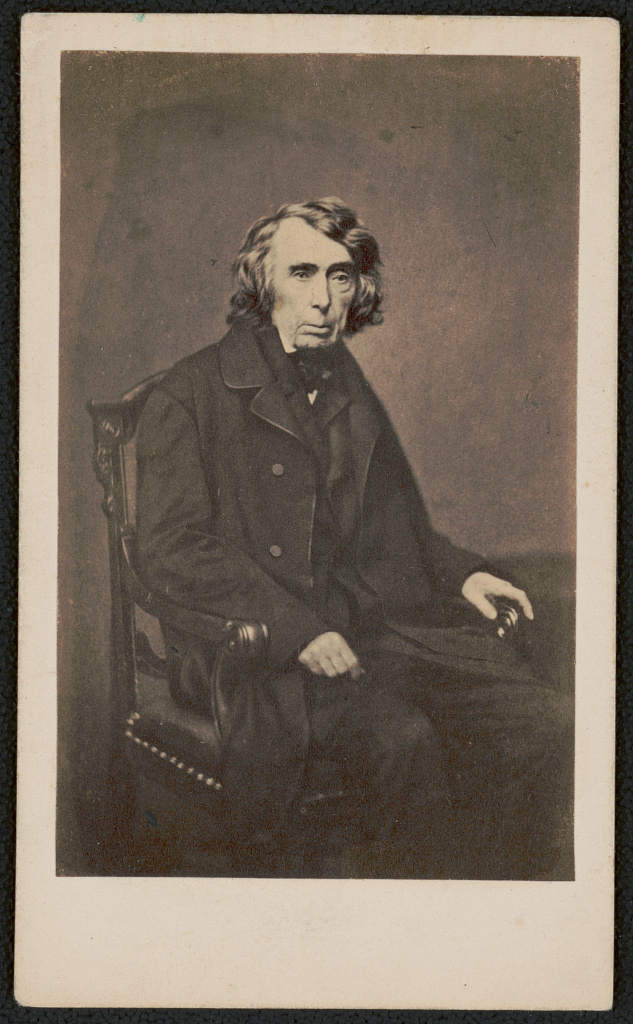

Questioning the Dred Scott Decision

In a recent seminar on “Slavery and Its Consequences,” DeMarco wondered why Roger Taney wrote his inflammatory ruling in the Dred Scott case. Couldn’t Taney have led the court to simply dismiss the case, on the grounds that Dred Scott, as an enslaved man, lacked citizenship rights and thus had no standing as a plaintiff? He asked Professor Eric Sands this question. Sands replied that Taney “thought he was playing the role of a statesman” when he wrote his opinion.

There were lots of readings to cover, and lots to discuss. The conversation moved on, leaving DeMarco wondering why Taney thought his opinion the work of a statesman. So, we emailed Sands to ask him about this. Sands replied:

“Yes, Taney could have made his ruling much simpler and far less pernicious by just denying Scott’s standing to sue—and then dismissing the case. There was no reason he needed to go further than this, declaring all blacks non-citizens, and then invalidating the Missouri Compromise—Well, other than the fact that, as I think I said in the seminar, Taney thought he was playing the role of a statesman. But DeMarco’s instincts on the case are spot on.

“I think Taney thought he had rectified the slavery issue (at least as it pertained to the territories). And part of his ruling was that depriving someone of their slaves in the territories was a violation of the Fifth Amendment—that is, of the clause stating: “No person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Taney’s ruling meant that slavery couldn’t be kept out of the territories.

“It’s kind of staggering how sweeping the ruling was. But, given its breadth, it’s not surprising the ruling led to crisis.”

After we sent DeMarco Sands’ response, he shared what Sands said with his students. “My students were surprised, suddenly realizing that a single person’s choices can have a major impact on American history. We compared the impact of Taney’s ruling to that of Stephen Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, and John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry. Which event played a greater role in triggering the crisis that led to the Civil War? Of course, the actions of Taney, Douglas and Brown all helped to bring the war.”

Dred Scott and Judicial Overreach

Sometimes, it’s the cautious inaction of earlier Americans that we need help understanding: why earlier Americans didn’t act more decisively to bring their actions into line with their convictions. DeMarco helped his students grapple with their frustration with Jefferson, whose financial indebtedness, it must be admitted, resulted in part from questionable decisions he made. (He entertained lavishly, sometimes to serve diplomatic purposes that he thought served the nation; and he thought his reputation as a gentleman required him to sign his name guaranteeing a friend’s loan. That friend defaulted, ruining Jefferson financially.) It is possible to deplore Jefferson’s personal failure to free his slaves while understanding the human flaws that led to that failure—and while honoring Jefferson for writing the Declaration.

At other times, history shows that those who act decisively can set in motion events they don’t anticipate. When Taney flattered himself that he could settle the question causing a fundamental sectional conflict, he actually inflamed the existing tensions.

“I try to help students understand that the world we live in did not emerge out of nothing. It is the result of other people’s choices,” DeMarco says. “We have to reckon with that. And we must remember it as we make our own choices.”