Meet Our Teachers

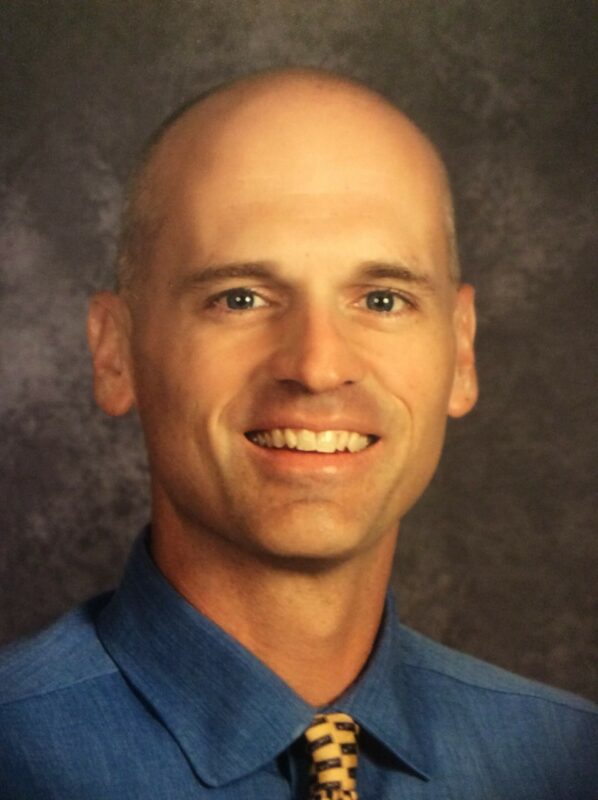

Vince Bradburn

Thinking Through the “Why” and “How” of History

Vince Bradburn, a 2020 graduate of the Master of Arts in American History and Government, entered the program seeking an intellectual challenge. Although he had plenty to do as a social studies teacher and as a coach of athletic and academic teams at Shelbyville High School in Indiana, he felt bored.

“Then the MAHG program came across my way. It’s the only program tailor-made for dorks like me who still want to be in the classroom. It would feed my own practice and craft while also positioning me to move onto another level—like teaching at community college or starting a PhD program down the road,” Bradburn said. The MAHG program is content-focused, completely unlike the Masters of Education program Bradburn had completed seven years earlier. All Bradburn’s coursework involved study in the primary documents of American history. Even the courses on governmental institutions take an historical approach, examining how those institutions developed from the time of the founding forward.

To fund his studies, Bradburn applied for a Madison Fellowship, and in 2015 was named the Madison Fellow for the State of Indiana. He began the coursework he needed before embarking on a thesis—one of the options for completing the degree—thinking this would best position him for further graduate study.

Bridging the Divide Between Philosophy and Practice

During the program, Bradburn made a surprising discovery. Although the MAHG offered no instruction in pedagogy whatsoever, Bradburn’s studies were improving his teaching practice. At the same time, they were alleviating the boredom he had earlier felt.

“One of the things the MAHG program does a very good job of,” Bradburn explained, is “bridging the divide between philosophy and practice. It places teachers in the role of students, giving us practice using primary documents. Through that exercise, I came out much more confident I could create opportunities for my students to do the same.”

Bradburn described the way teacher education generally works. “At the university you have a clinical setting designed to steep you in the philosophy of education.” During this training period aspiring teachers examine what others have theorized and reflect on their own goals as educators. But the clinical setting is “somewhat sterile. You begin teaching in secondary school”—encountering the resistance students naturally put up when asked to read difficult texts or think through challenging concepts—“and you think, ‘Oh, the philosophy doesn’t really apply to my students,’” Bradburn said.

He offered a vivid example. Earlier in his career as a teacher of American history, Bradburn planned what he expected to be a very engaging lesson on the Battle of Tippecanoe, a local legend in Indiana. He transcribed the words on an historical marker erected in 1974 at the site of the battle (the marker has since been replaced):

Urged by the Prophet, Tecumseh’s brother, Indians attacked the army of Gen. W. H. Harrison Nov. 7, 1811. The victory by Harrison broke Indian power.

“This marker was very much written from a particular perspective,” Bradburn said. He challenged his students to uncover competing perspectives on the battle by reading a range of primary documents, including the recorded testimony of Tecumseh himself. Then he asked them which perspective informed the historical marker. But the juniors in Bradburn’s general-level American history course “couldn’t care less. I was so disappointed. This was the cool stuff! This was the history publicly presented in our own moment. If you drove up to the northern part of the state, you would see this marker on the side of the road.” He wanted his students to ask themselves whether the marker told the whole story of Tippecanoe. “But the students were like, ‘Isn’t it time for lunch yet?’”

Bradburn realized he had not prepared his students sufficiently for this challenge. He shouldn’t have expected students “to immediately know how to read primary sources and analyze them. Generally speaking, they aren’t experienced enough yet; they don’t have the skills.”

Teaching the Skills of Primary Document Analysis

Imparting these skills is a pedagogical challenge. Bradburn has tried and tested a variety of creative approaches to teaching the skills, and now sees his students steadily growing more capable of working through primary documents.

To help students develop the skills of reading and critical analysis, Bradburn uses simple exercises at the beginning of each general-level history class, a different kind of exercise for each day of the week. (He calls these exercises “preambles,” because “I can’t stand the term ‘bell-ringer;’ it implies something inconsequential you ask students to do” while the teacher completes an administrative task.)

“My preambles target the skills that my students need, according to an assessment I give them at the beginning of the year,” Bradburn explains. “We may have ‘Storytime Monday,’ which focuses on auditory processing. I’ll give them a couple of questions to think about; then I’ll read a short document excerpt; then I’ll ask them to answer the questions I earlier posed.” The end of the week brings “I-Spy Fridays,” simple detective exercises. In the fall semester, Bradburn presents students with photos he’s taken around the town of Shelbyville. He has edited the photos to zoom in on particular details. “I ask students to figure out where each photo was taken. What they have to do is first identify at least three clues within the photos, then to guess, based on the clues, what the setting is. Students may say, ‘I see brick; it’s red brick; and there’s also a tree.’ Then I ask them where in town they think the photo was taken.

“This does two things,” Bradburn says. “I’m getting them to think about their local community; and I’m getting them to list evidence that will support a claim. That experience allows my grade-level kids to acquire the same skill that the AP US History students are learning. It’s not at the same level, but it’s the same skill.

“Later I transfer this skill to historical documents,” Bradburn continues, explaining his current approach to the Battle of Tippecanoe. He gives his grade-level juniors contrasting portraits of each of the two brothers, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa (“The Prophet”), who led the Native Americans who fought at Tippecanoe. “I place four different portraits throughout the room and ask them to describe each, without telling them that two of the paintings are of Tecumseh and two are of The Prophet. I ask, ‘What adjectives come to mind when you study this picture?’” Bradburn groups the students in pairs for this exercise. Students in each pair study portraits of the same person, “but each has a very different portrayal of that person. The adjectives they come up with should be very different.”

After students analyze the portraits, Bradburn gives them a paragraph of text from a primary document describing the same people. Once again, Bradburn uses contrasting descriptions. “I ask, which of the images does the text describe?” The exercise moves students from an image to a text, while “chunking out the reading in smaller bites. It’s something that they can do, feeling confidence that they can be successful at it.” At the same time, the exercise conveys a deeper lesson about history: the account we read depends on the perspective of the historian who drew the portrait of the past.

Bradburn has developed this creative pedagogy on his own. But his MAHG studies made him confident that he could adapt his practices enough to eventually reach his goal. This is because MAHG helped Bradburn develop his own skills of reading and analysis. “Through MAHG, I’ve been a student myself in an educational setting like the one I want for my students. If I as a teacher am not thinking through the why and the how of history, then I can’t expect the kids to think it through. MAHG forced me as a student to own my why and how.”

Recognizing Ourselves in the Story

Each MAHG course was an intense intellectual exercise that Bradburn thoroughly enjoyed. Yet, because of the focus on first-person accounts of history, Bradburn found himself exercising socio-emotional muscles as well. He became more aware that human choices drive historical events, and that understanding these choices requires “historical empathy.”

Researching his thesis, Decision-making on the Frontier: Federalism in the Eradication of Slavery in Indiana (which was honored with a MAHG Chairman’s Award), “really opened my eyes to the complexities of human experience,” Bradburn says. He uncovered the little-known story of slavery’s temporary survival in the territory covered by the Northwest Ordinance. Passed in by Congress in 1787, it contained a provision barring slavery from the territory. Yet the wording of the provision was “porous” enough to allow a small number of settlers to retain slaves they had brought to the territory before the ordinance was passed. In some cases, the laws on indentured servitude were interpreted in a way that allowed for slavery to continue for years after 1787. In fact, Congress received requests from the territory to extend slavery through the early 1800s.

An earlier law to bar slavery from the territory had been written to exclude any exceptions. This bill stalled in committee, because of the “nay” vote of one member of one state delegation.

The voice of a single individual would have prevented this abominable crime from spreading itself over the new country. Thus, we see the fate of millions unborn hanging on the tongue of one man. And heaven was silent in that awful moment.

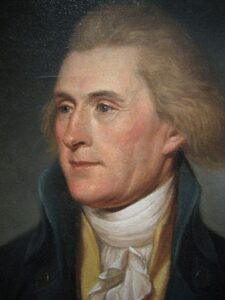

Bradburn found Jefferson’s comment fascinating. “Here’s a man who owned slaves, himself perpetuating the practice, but privately lamenting it,” Bradburn said. The comment called to mind a deleted passage in Jefferson’s original draft of the Declaration, a paragraph accusing King George III of imposing the slave trade on the colonies. Today, Bradburn shows both passages to his students, asking them what the contradiction between Jefferson’s words and practices reveal about the him.

He asks students to take Jefferson’s words seriously, pushing back if they try to excuse him as a man with the prejudices of his time or if they dismiss him as a hypocrite. Some students conclude Jefferson experienced an inner turmoil. Unwilling to impoverish himself and his heirs by freeing the people he held in slavery, he tried to save other Americans from facing the same decision.

“The great value of exposing the whole story, warts and all, is that it helps us recognize ourselves in that story,” Bradburn says. He wants students to reflect on their own decisions, realizing, “I’m a flawed individual, just like the person I’m reading about.”

All of Bradburn’s teaching practices—from “I-Spy Fridays” to serious conversation about difficult primary documents—help students see themselves as part of a civic community to which they are responsible. Adolescents “tend to see themselves as disconnected” from their communities, Bradburn observes. “But as we go through the I-Spy Fridays, I hear back from kids, ‘Hey, I saw that one building in last week’s I-spy!’ I laugh, ‘Well, that really stuck with you!’ But really, what they’re telling me is that what we’re doing in the classroom is connecting to what they’re doing when they leave class.” Even such small connections help students realize that education involves more than completing routine tasks. It involves “problem-solving,” and the acquisition of those critical thinking skills that will enable them to “anticipate the consequences of their actions” for themselves and others.