Understanding the Great Depression

Today we feature an interview with Professor John Moser, author of The Great Depression and The New Deal, a concise history of this critical juncture in American history. The first of a new Teaching American History series, it is a highly readable account of a period that has been the subject of myths and misinterpretations in textbooks and histories. Few Americans understand the economic conditions that produced the Great Depression, and many do not understand the factors that brought an end to the crisis.

The Great Depression and The New Deal, like the other volumes planned for the series (Discovery and Settlement; the Founding; the Civil War; the Emergence of Modern America; and America in the Age of the Vietnam War) covers, in about 150 pages, a turning point in our nation’s history, including the factors that led to it and the political and cultural changes it wrought. It includes a timeline of events, a list of works for further reading, and an index. The text is linked (and hyperlinked in its downloadable digital version) to TAH’s core document collection on the same period, itself edited by Moser.

Professor John Moser chairs both the Department of History and Political Science at Ashland University and Teaching American History’s graduate program, the Master of Arts in American History and Government, based at Ashland University. Moser’s many books and articles, which include The Global Great Depression and the Coming of World War II (Routledge 2015), cover a wide range of subjects, from the world wars to Japanese foreign policy to the cultural significance of comic books.

We asked Professor Moser to explain, first of all, what students and teachers can learn by studying the Great Depression and the New Deal.

Why is it important for Americans today to understand the history of the Great Depression? Haven’t many of the economic factors that led to this calamity since been resolved?

Well, we like to think that. The fact is, there are many people who still misunderstand why the Great Depression occurred; they do not grasp the central role monetary policy played in causing the crisis. So, they do not grasp the economic lessons this history offers.

Second, we still suffer periodic economic downturns. God willing, we will never have another one as severe as the Great Depression. But there is comfort in looking back to the Great Depression when new economic crises occur, just as, when 9/11 happened, we looked to the historical precedent of Pearl Harbor. In many ways, 9/11 confronted us with a shocking, absolutely new kind of attack. But when we remembered 1941, we could say, “Wait a minute, that surprise attack killed about the same number of people and did a comparable amount of damage. Yet we rebounded and eventually won the war.” I think there is something comforting in understanding what the Great Depression was all about, and putting subsequent crises into that historical context.

You mentioned monetary policy. Your short history gives a brief and cogent explanation of how restrictions in the money supply, largely as a result of adherence to the gold standard, led to the Depression. Why is this not better understood?

It’s a misunderstanding that has persisted ever since the Great Depression unfolded. Remember that the Depression occurred against the backdrop of the 1920s, when Americans seemed to be more prosperous than they ever had been before. They were buying things that earlier they never could have afforded. At the same time, people worried about the effect of this growing materialism. There was lots of talk about immorality among young people, who were driving about unsupervised in automobiles, drinking in speakeasies, and dancing to jazz music. It became easy to see these things as symptoms of a larger attitude of selfishness and carelessness that brought the crisis about.

I’m now reading a colleague’s manuscript about New Deal crime policy. I wish I had read it a year ago, so I could have brought some of its insights into my short history. During the Roosevelt administration, law enforcement agencies grew in terms of their budgets and the power they wielded—because of public demand. Americans at the time didn’t see the Depression simply as an economic crisis; they saw a crisis of morality.

One thinks of the many hoboes traveling around looking for work. Did people find them unsettling?

That was part of it: weren’t the so-called tramps a menace to the American way? But Americans also complained of greedy businessman who acted only in their own self-interest and didn’t think about the public welfare. And during Prohibition—which was not repealed until the end of 1933—they had watched organized crime grow. Overall, there was a crime boom in the early 1930s, and the Roosevelt administration committed itself to ending it. Sure enough, crime rates went down—but of course, that happened in part because of the economic recovery.

If people were worried about crime, it seems they were unsure who committed it—the poor, or those exploiting the poor? I’m thinking of Hoover’s oscillations. Hoover called the Bonus Army a “mob” and empowered Douglas MacArthur to use force to disperse them. Yet Hoover also signed the Norris-LaGuardia Act, which banned courts from issuing injunctions to break strikes.

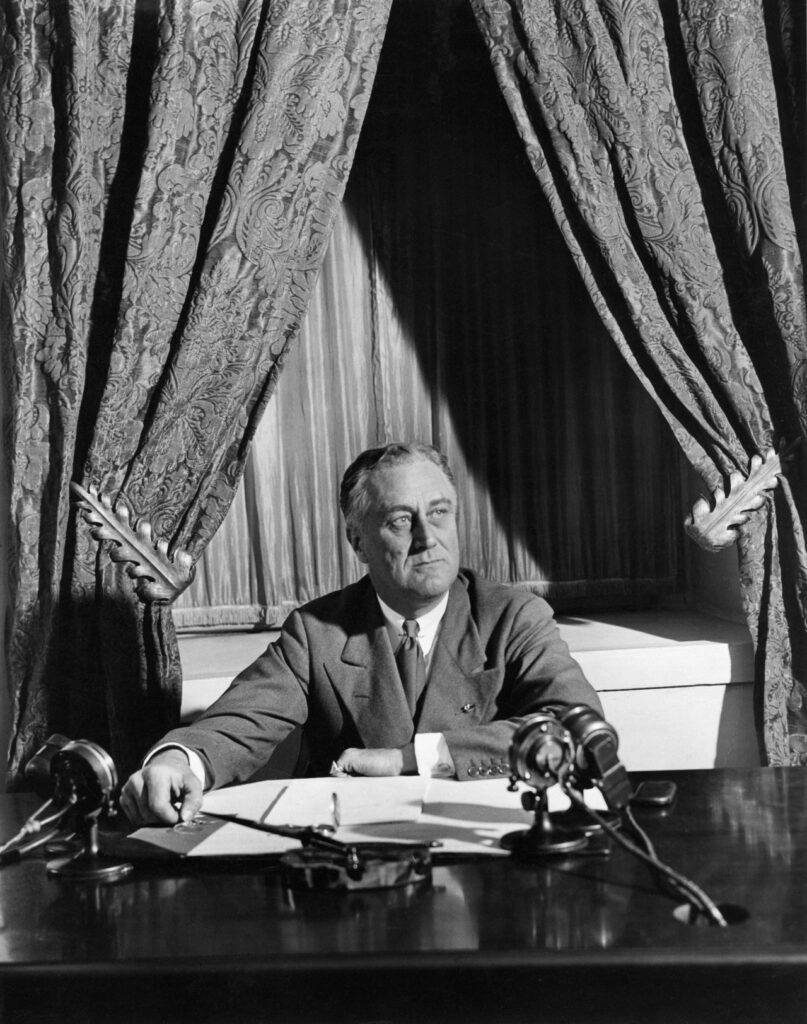

Hoover saw the Depression as a technical problem and, engineer that he was, set out to solve it. He never tried to personalize the issue the way that Roosevelt did. For FDR the Depression was the work of selfish, greedy businessmen and bankers. Even in 1932 Al Smith, one of Roosevelt’s major rivals for the Democratic Party’s nomination for president, accused him of engaging in “class warfare.”

I’m still amazed at how often one sees Hoover depicted in popular histories as a do-nothing president. In fact, he was highly activist. He spent more money in peacetime than any of his predecessors—and some of the things he did, frankly, made things worse.

The popular view of Hoover as the conservative who didn’t care derives from Hoover’s personality. He was always an engineer; he saw himself as an expert solving technical problems. Of course, he cared about the plight of ordinary Americans; he would have been a monster not to care. Yet he couldn’t project warmth and empathy. In that sense, the contrast in personality between him and FDR was real. Still, they were both very active presidents.

Did Roosevelt’s New Deal policies end the Great Depression—or, at least, put the economy on a path to recovery?

Roosevelt did some things that helped. Certainly, he restored faith in the banking system—although it’s worth pointing out that most of FDR’s actions to stabilize banking were things that Hoover had planned to do. The idea for the Emergency Banking Act—to close all the banks and then have examiners look at their situations and decide which ones to reopen—that was a Hoover idea, and in fact the policy FDR executed was put together by holdovers from the Hoover administration. It’s true enough that FDR’s radio address did a lot to restore confidence.

If all you do is look at the Depression, you might get the idea that banking crises were a new feature of American life, but in fact, they happened all the time. There just were more of them between 1930 and 1933, and the one that occurred at the beginning of 1933 was the worst ever in American history. The Emergency Banking Act resulted in an immediate boost to the economy.

But what’s often forgotten is that after that, things leveled off. You don’t see an upward trend until 1934. Then there is steady upward progress through early 1937. That helps to explain why FDR wins by a landslide 1936. Yet soon after, in the middle of 1937, the economy takes another nosedive. This history, I think, really undercuts the idea that the New Deal ended the Depression.

Other forces had a greater influence on the US economy. The biggest one was the flow of gold into the United States, which was related almost entirely to the rising threat of war in Europe and Asia. Remember, the Depression was world-wide. When war threatened, if you were a wealthy person abroad, you wanted to send your hard currency to the United States where you thought it would be protected. As a result, Americans’ gold reserves built up tremendously, allowing for significant economic improvement. So much so, though, that in late 1936 and early 1937, FDR and some of his advisers started to worry—amazingly—about inflation. Despite their earlier anxiety to raise prices, now they thought prices were going up too fast.

FDR and his team were not the only ones to worry inordinately about inflation. Hoover had also; that’s why he raised taxes and slashed spending and why, under Hoover, the Federal Reserve Bank raised interest rates. The fear was that if we went off the gold standard, we’d have runaway inflation. Everybody looked to the example of Germany in the early 1920s. That was a nightmare scenario.

Likewise, at the end of 1936 and in early 1937, FDR and some of his advisers, like Henry Morgenthau, began worrying that the economy would overheat and prices would rise too much. So, the Federal Reserve starts increasing the requirement for gold reserves that banks had to keep on hand, and interest rates started to go up. Roosevelt also decided to cut back on spending. Also, in 1937, Social Security taxes were collected for the first time ever. With money being taken out of the economy in all these ways, a serious setback occurred.

By 1940, things were looking better again. But I don’t think the New Deal brought this improvement. The flow of gold brought it. And by 1940, of course, you’ve got increasing spending on the armed forces, not just in the United States, but world-wide.

By the way, early in the Depression commodity prices—on basic goods like wheat, cotton, pork, steel, etc.—dropped to really low levels. So, much of New Deal policy early on was aimed at forcing prices upward. If you make things more expensive, then it’s going to create an upward spiral: wages will go up, prices will go up, wages will rise more, and so on. Hence the fear of inflation and the efforts to restrict the money supply. Fortunately, in 1937, wealthy investors abroad were still seeking safe havens for their money; and around the world countries were building up their military forces, effectively bidding up the price of all these basic commodities. That certainly helped pull the US economy out of a second tailspin.

One policy that was bitterly criticized was the destruction of what was perceived as excessive farm produce, at a time when many people were hungry. Did that policy do any good?

It’s not clear to me how much of an effect it had on commodity prices. The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) increased farm income, because farmers received subsidies for not farming certain crops. The aim of the policy was to increase farm commodity prices. But I don’t think this happened because of the voluntary curtailment of production. Rather, things were getting more expensive everywhere as a result of the rearmament campaign in most of the world.

Of course, then as now, a disproportionate amount of the benefit of farm subsidies went to the big farmers—to agribusiness. Southern plantation owners really made out well from it—whereas African American sharecroppers got the short end of the stick. When large farmers were paid not to produce as much cotton, sharecroppers were put out of work.

In your conclusion you cite one of FDR’s early advisors, who said that to assume that the New Deal operated according to some unified plan would be like assuming

. . . that the accumulation of stuffed snakes, baseball pictures, school flags, old tennis shoes, carpenter’s tools, and chemistry sets in a boy’s bedroom could have been put there by an interior decorator.

— Raymond Moley

This raises the question, what did FDR understand himself to be doing? What was his animating idea?

His animating idea was to improve the situation. I’m not sure that he had a clear idea of what that meant, even when he entered the White House, when the most immediate thing was to address the banking crisis. He had a very talented group of advisers, many of whom disagreed with one another vehemently. To those butting heads, he usually said something like, “Okay, you two get together and come up with something satisfactory to you both.” That helps to explain why so many different approaches were stitched together. I don’t want to suggest that FDR wasn’t involved in the process. He absolutely was. His advisors showed him their ideas and FDR would say either, “this looks good” or “no, work out another plan.” But he did not initiate policy, except on very rare occasions, such as when he suggested the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Not all the policies came from members of his brain trust; some came from members of Congress. Senator Robert F. Wagner of New York played an extremely important role, even though he was not a member of the administration. The “New Deal” encompasses all the legislation that FDR came out in favor of.

Take the National Labor Relations Act. For a long time, Roosevelt was ambivalent about it, even though today it’s remembered as a key part of the New Deal. He did not endorse it until it was clear it would pass. In general, members of Roosevelt’s administration felt ambivalent about organized labor. I think this goes back to the go back to the Progressive Era.

Would you explain that?

Well, certainly the idea that workers join unions and bargain collectively to wring higher pay and other concessions out of management has a long and distinguished history. However, the progressives of the early 20th century preferred that government guarantee fair wages, safe working conditions, and a limited work day. Progressive administrations hated labor strikes. They were disruptive. They pointed up the internal conflicts that government was supposed to smooth out. By contrast, union leaders—such as Samuel Gompers of the AFL (who was no longer around by the 1930s)—said, in essence, “you can’t trust the government to give us this stuff. Even if they do, they can always take it away again. It’s safer just to forget about the government and focus on unionizing.” In 1934, when a wave of labor unrest affected industry in the United States, the administration wanted to settle the strikes quickly, lest they interfere with recovery. It’s only in 1935, with the National Labor Relations Act, that the administration goes all in on organized labor. And organized labor repays the favor in the 1936 elections. That election established the relationship between the unions and the Democratic Party that to a great extent still exists today.

That’s interesting, especially when you think of A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, successfully pressuring FDR during the Second World War to integrate military industries.

The African American votes that went for Roosevelt in 1936 came from northern states, where public works programs of the New Deal didn’t discriminate—or at least, didn’t discriminate much. Also, there were people in the administration who genuinely cared about civil rights, which made a big difference. Eleanor Roosevelt was a was a very powerful asset for the administration. She was outspoken, whereas FDR would not even push an anti-lynching bill. He did not want to offend white southern Democrats whose votes he needed.

This leads back to something we talked about briefly with the AAA: the New Deal and civil rights. It’s very interesting to me that African Americans went so heavily for Roosevelt in 1936, considering how little the New Deal did for black people. Not only the AAA subsidies but also Social Security did little for them, since agricultural workers and domestic help were not covered by Social Security. One must remember, of course, that in 1936, the vast majority of African Americans in the South couldn’t vote.

What lessons can we learn from the story you tell in this book?

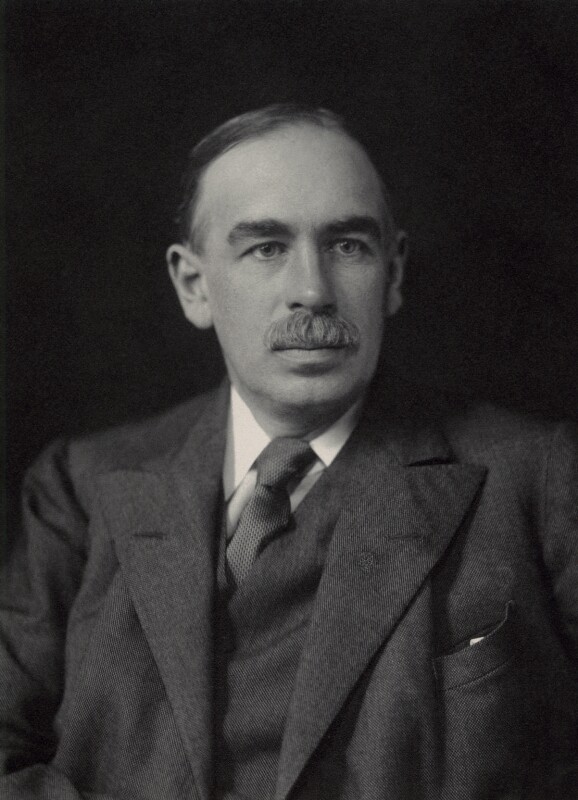

As I said at the outset, monetary policy matters. It’s also important to understand that the government under Roosevelt did not spend its way out of the Depression. The extent to which FDR followed the economic theories of John Maynard Keynes has been greatly overstated. Keynes famously wrote two open letters to FDR, advising him that he was focusing on the wrong things. “It’s not rocket science!” he argued, in essence; “just spend a lot of money! That will increase aggregate demand and fix the problems.” Keynes also criticized the NLRA, saying “We don’t need new regulations right now. That will upset business. Worry about reforming industry later.”

Roosevelt himself, to an extent that is often forgotten, tended toward fiscal conservativism. When he criticized Hoover in the 1932 campaign for spending too much, he wasn’t being disingenuous. Although he knew money had to be spent to deal with the crisis, one of his first initiatives was to ask Congress to pass an Economy Act slashing pay for government employees and cutting spending in a range of areas. Even as he supported programs that cost money, he tried to find savings elsewhere, by either reducing spending or raising taxes.

This debate certainly seems relevant to the discussion in Congress today.

Keep in mind that during the Great Depression, there was much more room to spend, because debt was such a small percentage of GDP. We have less wiggle room for that now. Today, the amount that the United States government has to spend every year just to service the debt really constrains what government can do to address an economic crisis.

Keynes was right that governments could use deficit spending to stimulate an economy. But he also thought that governments should rein in spending during economic boom times. He didn’t seem to be aware that public spending always benefits some special interest, and those interests will fight hard to make sure that the spending never goes away. So we find ourselves in the position we’re in today; where very little gets cut, and the national debt keeps piling up.

Another lesson we’ve learned is that the gold standard was not nearly as important as it was believed to be in the 1920s and 1930s. Arguably the best monetary system that the United States ever had was the one put into place at the end of World War II, with the creation of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. The dollar was tied to gold at a certain rate, but not at the level of the old gold standard. And of course, the FDR himself, after taking us off the gold standard in 1933, returned the country to the gold standard in 1934. But he set the price of the dollar at roughly half of what it had been.

As an historical observation, the notion that a president is in some way responsible for the health of the economy developed during this period. Previously, when economic downturns occurred, the party in power always suffered. But it had not been previously expected that the president would devise a strategy for economic recovery. The model that FDR followed was much like the model for World War I. The United States had not been ready for war in 1917. We had a tiny military establishment and almost no war-related industry, but through the actions of smart people running the economy, we mobilized and were able to win the war. On the campaign trail in 1932, FDR again and again mentions his work in the Wilson administration as Secretary of the Navy. We can use the same kind of know-how and hard work to fight this crisis as we used to fight World War I, he said.

What is the most important idea you hope students and teachers take from your book?

Many teachers rely on textbooks, and textbooks have not changed much in their interpretation of the Great Depression and New Deal. They still echo the explanations offered by journalists of the era.

Journalism, they say, is the first draft of history. A reporter named Frederick Lewis Allen published a book in the early 1930s called Only Yesterday. It’s such a fun book, and I am embarrassed to say that I have assigned it. In fact, I would still assign parts of it—but not Allen’s analysis of the economic problem of this period as a combination of overproduction and under-consumption.

Economists have been telling a different story. Although I didn’t set out in this book to blaze any new trails, I do think this book brings some of the insights of economists into the story. I am not an economist, but I have read a fair amount of their commentary. Not just conservative economists, but the economics profession in general looks at the Great Depression and says, this was fundamentally a monetary problem, which required a monetary solution.

You can find John Moser’s book, The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Concise History, in the TAH Bookstore