“Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing:” 122 Years Later

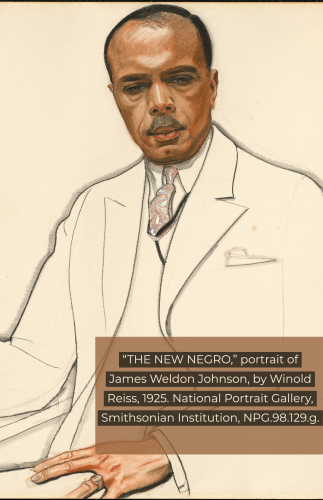

A poem that went on to be adopted as the “black national anthem” – “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” – was first publicly performed 122 years ago, at a community event celebrating Lincoln’s birthday in Jacksonville, Florida. The event took place at Stanton School, a public school for African Americans (founded during Reconstruction and named in honor of Lincoln’s War Secretary). The school principal, James Weldon Johnson, had written the song’s lyrics, while his brother John Rosamond Johnson wrote the musical setting and conducted a choir of 500 school children in its performance.

The Ambition and Genius of the Johnson Brothers

James and Rosamond Johnson were young men of great talent seeking avenues for large ambitions. They had been raised to discount any limitations to curiosity and determined effort. Their mother, the first black teacher hired at Stanton School following Reconstruction, taught them to read and started them on their musical education before they entered school. Their father was head waiter at a resort hotel and well respected in the community.

Rosamond, the younger brother, settled on a career in music. He studied at the New England Conservatory and, after a brief period teaching music in Jacksonville, made a career in musical theater. James Weldon Johnson, who went on to a remarkable career in literature, theater, diplomacy, and social activism, chose Atlanta University, one of the first colleges for black students founded by the American Missionary Society after the Civil War. He later wrote that he did not become conscious of America’s race problem until he went to Atlanta. There he met students from poor rural families struggling against Jim Crow restrictions, engaged in lengthy discussions of racial discrimination, and imbibed a sense of responsibility to enlarge opportunities for other black Americans.

James Weldon Johnson’s Remarkable Career

Throughout his life James Johnson embraced this mission, balancing it against what he called a “love of venture” that inspired him to pursue more personal ambitions. In many ways he fused the two goals. In 1894, shortly after taking over the principal’s position at Stanton, he decided to expand the curriculum beyond the eighth grade. Before letting the superintendent of schools in on his plans, he had already brought his oldest students through the first year of high school; the local school board then “accepted a fait accompli,” he wrote.

Soon after, without abandoning his principal’s position, he founded The Daily American, the first American newspaper tailored for an African American audience. This experiment was less successful; it closed within a year. He turned from that venture to studying law in his off hours, with the help of a local white lawyer. The first African American to pass the Florida bar exam, he opened a small law practice which he soon shared with a black friend whom he had in turn helped to pass the bar exam.

A New Venture

Meanwhile, the Johnson brothers had been spending summers in New York City, writing songs for Tin Pan Alley. Shortly after the turn of the century, they felt their options for self-fulfillment were narrowing. A devastating fire had destroyed much of Jacksonville, in the wake of which racial discrimination increased. Shortly after writing “Lift Ev’ry Voice,” Johnson and his brother moved to New York City to pursue careers in musical theater full-time.

With a colleague, Bob Cole, they produced about 200 songs for Broadway shows, while also performing as a trio. They elaborated African American musical idioms while avoiding the stereotypes familiar from minstrel shows. That they came to be called “those ebony Offenbachs” suggests they gained surprised respect. Among their creations was a six-song suite, The Evolution of Ragtime.

A Literary, Political and Activist Life

During this period, Johnson studied creative writing at Columbia University and became active in Republican party politics. This latter work led to his appointment as consul to Venezuela in 1906. Consular work in Venezuela was not very demanding, and Johnson used the three years he spent in Venezuela to write his only novel, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man. In this story of a light-skinned Negro who eventually decides to “pass” as white, Johnson offered his most pessimistic assessment of African American possibilities, perhaps because his ex-patriot situation gave him the distance to reflect on America’s failure to ensure racial equality.

In 1909 Johnson was transferred from Venezuela to a more challenging consular position in Nicaragua, at a time when the Taft administration was anxiously monitoring political developments in the central American nation (it would eventually land troops there). After Woodrow Wilson was elected and Democrats began controlling patronage positions in the foreign service, Johnson resigned, returning to New York to become an editorial writer for The New York Age.

In 1916, W. E. B. Du Bois asked Johnson to become National Field Secretary for the NAACP. In this role, Johnson opened NAACP branches around the country and investigated incidents of racial violence. He went on to become executive secretary of the NAACP in 1920, holding the position during a decade of racist backlash against black veterans of World War I and black migrants from the South who were pursuing employment in Northern industry. Johnson worked successfully to build NAACP membership and political influence—but his lobbying efforts in favor of a federal anti-lynching bill failed to overcome Southern resistance.

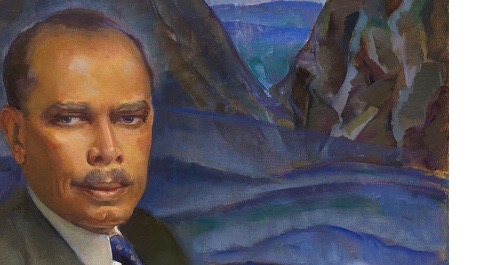

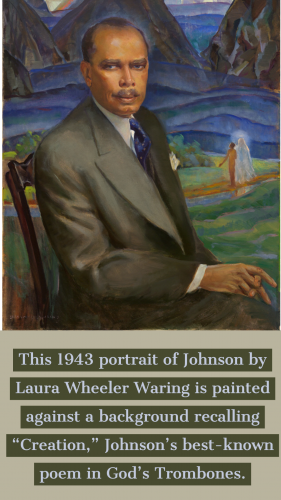

As always before, Weldon pursued a personal calling concurrently with intense political advocacy. He published four books in the 1920s: an anthology of American Negro poetry, two collections of spirituals, and his own poetry collection, God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse. In 1930 he published another poetry collection, Saint Peter Relates an Incident of the Resurrection Day, along with a survey of African American cultural contributions to New York life, Black Manhattan.

At the end of that year, Johnson, wanting more time to write, retired from the NAACP and took a part-time teaching position at Fisk University. He wrote his own autobiography, Along This Way, as well as an argument for racial integration, Negro Americans, What Now? before his accidental death in 1938, while riding in a car struck by a train at an unguarded rail crossing.

Johnson’s Legacy

Arguably, Johnson devoted his entire life—certainly his literary life—to raising awareness of and respect for African American culture. His poem “Oh Black and Unknown Bards” uses the elevated style of European poetry to marvel at the musical creativity of enslaved African Americans. In God’s Trombones he brought the musical rhythms of African American preaching into a new kind of American lyric, one that captured the Biblical insights of these same preachers.

From a musical point of view, I’d argue, Johnson’s most remembered composition, “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” also fuses Euro- and African-American styles. John Rosamond Johnson’s setting is a victory march in 6/8 time. In it one hears the steady tramp of feet—left, right, left—punctuated by triplets that make the melody skip, turning the march into a waltz. For me, it evokes a mass of dancing humanity ascending a celestial highway. The song can be sung slowly and magisterially or—as often in today’s performances—in cut time, with soaring classical harmonies. Well-loved for over a century, it has been reimagined to combine the march style with R&B and funk rhythms by Ray Charles and, on another occasion, by a team of Al Green with Deniece Williams and others. Recently, Beyoncé performed it with dancers. In later life, Johnson said:

The lines of this song repay me in an elation, almost of exquisite anguish, whenever I hear them sung by Negro children.

The poem assumes that victory over racist injustice is nearly won, at the same time suggesting that this victory belongs to the kingdom of God, once mankind fully heeds God’s will for justice on earth. No wonder that Johnson, hearing his song taken up by school children across the South, felt an “exquisite anguish” at so much hope, so joyously broadcast to a still-flawed world.