400 Years Ago This Week: The Pilgrims Land at Plymouth (but not necessarily on a rock)

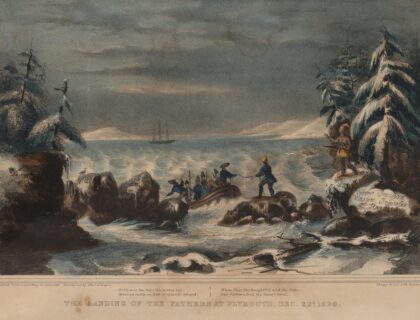

Although we remember the Pilgrims most commonly in November, it was actually in December of 1620 that they first set foot on the shore of Massachusetts. Although no actual stone is mentioned in any of the contemporary accounts, oral tradition in the area tells us the first steps on New England’s shores were made onto a large(ish) stone nestled in the harbor. Artistic depictions of the event tend towards the grandiose and epic, highlighting a few lone voyagers against a desolate landscape.

Some include figures of Native Americans on the periphery, allusions to the famously helpful Tisquantum (Squanto), his political leader, Massasoit, and their Wampanoag tribe among whom the Pilgrims settled.

Others–again drawing on oral tradition– depict a young woman (Mary Chilton) so eager to set foot on land that she literally jumps out of the boat nearest shore, wading through the shallows to be the first on land.

But what really happened at the landing?

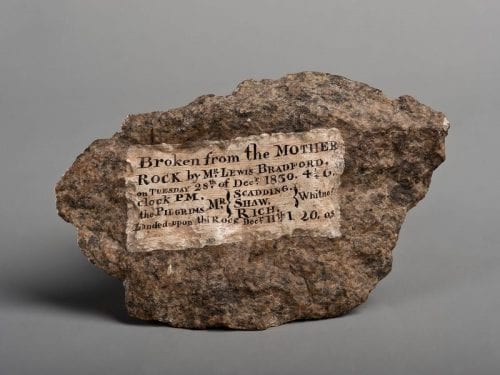

There is, in fact, a stone nestled into the harbor near Plymouth that has long been the object of regional pride as a marker of the Pilgrims’ brave resistance to an overbearing monarch and his religious persecution. Over the centuries, visitors to the site regularly chiseled off chunks of the stone as tangible reminders of their visit to the “Mother Rock” (or, more popularly, Plymouth Rock).

In the Revolutionary period, the stone became a symbol of the Patriot cause. It was broken in two during an attempt to move it from the shore to a more prominent position in the town square. The two pieces were reunited on the shore in the 1880s, and the date 1620 carved into the rock. The current pavilion over the site was erected as part of the tercentennial celebrations, and for the last hundred years, the rock has remained relatively safe from both natural and human assault under its sheltering eaves.

Whether anyone actually stepped on the stone, however, still remains doubtful.

According to William Bradford, the Pilgrims disembarked from their ships at night, and during a storm. In his account of the colony’s early history, Bradford notes that the company spent several weeks exploring the coastline for a suitable location for the colony. Late in the evening of the 15th of December, 1620, their pilot spotted a harbor, and the company decided at last to go ashore. a. However, conditions were hardly ideal for a landing:

The storm increasing, & night drawing on, they bore what sail they could to get in, while they could see. But herewith they broke their mast in 3 pieces, & their sail fell overboard, in a very grown sea, so as they had like to have been cast away; yet by God’s mercy they recovered themselves, & having ye flood [tide] with them, struck into the harbor. But when it came too, the pilot was deceived…he & the master mate would have run her ashore, in a cove full of breakers, before the wind. But a lusty seaman who steered, bade those which rowed, if they were men, [to turn] about with her, or else they were all cast away; which they did with speed. So he bid them be of good cheer & row lustly, for there was a fair sound [harbor] before them, & he doubted not but they should find one place or other where they might ride in safety. And though it was very darke, and rained sore, yet in the end they got [there] in safety. …

But though this had been a day & night of much trouble & danger unto them, yet God gave them a morning of comfort & refreshing (as usually he doth to his children), for the next day was a faire sunshining day, and they found themselves to be on an island secure from the Indians, where they might dry their stuff, fixe their pieces, & rest themselves, and gave God thanks for his mercies, in their manifold deliverances. And this being the last day of the week, they prepared there to keep the Sabbath. On Monday they sounded the harbor, and found it fit for shipping; and marched into the land, & found diverse cornfields, & little running brooks, a place (as they supposed) fit for situation; at least it was the best they could find, and the season, & their presente necessity, made them glad to accept of it. So they returned to their ship again with this news to the rest of their people, which did much comfort their hearts.

Of Plymouth Plantation, Book 1, Chapter 10

Bradford’s company of settlers spent another ten days scouting the location to ensure that it truly was adequate for their purposes and to gather the materials needed to commence building. Construction began on December 25. The Pilgrims did not observe Christmas Day, for they regarded it as a “popish” holiday—although, after months on ship, they might well have been so eager to get settled on land, they would have worked anyway! They “began to erect the first house for common use to receive them and their goods.” Although many of company were weak or ill from the long sea voyage, for the next several days “so many as could, went to work on the hill where we purposed to build our platform for our ordnance, and which doth command all the plain and the bay, and from whence we may see far into the sea, and might be easier impaled [that is encircled by a fort], having two rows of houses and a fair street.” (Mourt’s Relation (London 1622).

No mention at all was made of the stone that would become such a fixed symbol in American origin narratives. The truth of the “rock” remains a mystery, a reminder that history is seldom as cut and dried as we like to think it is.