Madison and Jefferson Discuss the Bill of Rights

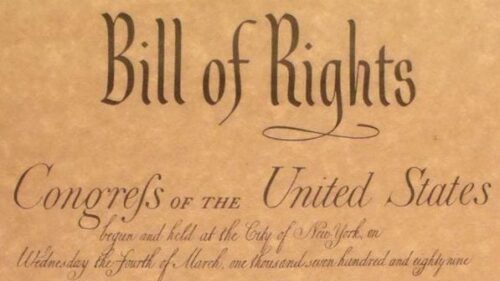

The first ten amendments to the Constitution, known to us as the Bill of Rights, were ratified on this day (December 15) in 1791. These amendments grew out of discussions that occurred during the debate over ratification of the Constitution. An early and illuminating version of this debate occurred in an exchange of letters between James Madison and Thomas Jefferson. Our post today is is a slightly revised version of document introductions written by Ashbrook Senior Fellow Gordon Lloyd for his document collection, The Bill of Rights, available at the tah.org bookstore.

In October 1787, James Madison sent a copy of the newly signed Constitution to Thomas Jefferson, who was serving in Paris as Ambassador to France. In his cover letter, Madison explained that the Constitution was a vital improvement in structure and power over the Articles of Confederation. He wished, however, that more checks and balances had been included. In his response to Madison, written toward the end of December 1787, Jefferson first summarized what he liked about the new constitution. He was “captivated” by what the delegates to the convention called the “partly national, partly federal” compromise. Jefferson then turned to “what I do not like.” He was troubled by two omissions. He wanted a bill of rights, and mentioned six rights that ought to be stated “clearly and without sophisms: freedom of religion, freedom of the press, protection against standing armies, restriction against monopolies, the eternal and unremitting force of the habeas corpus law, and trials by jury.” He also wanted the President limited to two terms in office.

In December 1787, as Jefferson was responding to his friend’s letter about the Constitution, Madison was focused not on adding a bill of rights but on getting the Constitution through the ratification process. The new framework of government would in itself, he felt, better secure the rights of American citizens than would what he called “parchment barriers” on that government. Nor did Madison want to reopen negotiations over the framework; a second convention might well abandon the carefully balanced compromises achieved during the first.

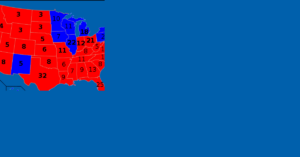

At this point, the ratification process was progressing without substantial opposition. Three states had ratified the Constitution and two more were about to do so. Only the Pennsylvania Minority Report, prepared by those who had opposed the Constitution, raised serious questions. Nevertheless, Jefferson’s concern about the absence of a Bill of Rights had become a prominent theme in the pamphlet literature in fall 1787.

On July 24, 1788, Madison wrote to Jefferson in Paris that the US Constitution had been ratified, thus avoiding the danger of a second convention, as well as the adoption of unfriendly amendments as a condition for ratification. Madison was relieved and optimistic. Jefferson, however, reminded Madison that there was still much work to be done. The Constitution was a “good canvas” that needed to be retouched with “a bill of rights.” Jefferson’s letter found Madison now willing to entertain such an idea—as long as it did not undermine what the Constitution had already achieved. Jefferson was less worried by the dangers of constitutional revision. This remained a point of difference between the two.

In his response to Jefferson’s urgings, Madison now claimed that he had always been in favor of a Bill of Rights. Scholars have disagreed over Madison’s “apparent conversion” in favor a bill of rights. Was Madison flip-flopping from his earlier view, having seen that support for a bill of rights was popular, because he hoped to win a seat in the First Congress? Or was he acknowledging the wisdom of Jefferson’s arguments—and those of other prominent leaders, who approved the new Constitution but thought it lacked certain necessary protections for individual and state rights?

Whatever combination of motives informed Madison’s letter, we can read it as a first draft of his more famous and polished June 8, 1789 speech on behalf of a bill of rights. In this speech, Madison called for amendments to the Constitution that included four of the rights Jefferson mentioned. He did not mention habeas corpus, already covered in Article I, section 9, or a restriction on monopolies. The four rights he did mention, along with others, became part of the Bill of Rights that would be ratified in 1791.