50 Core American Docs: Teaching Political Rhetoric

Today’s blog is the final entry in our miniseries on how teachers use 50 Core American Documents in their classroom. The author is Malik Ali, a Tukman Distinguished Teacher of History and a MAHG grad. He is a teacher at Branson, in Ross, California.

As the American primary system has become more firmly set in recent history (particularly over the last 50 years or so), the national party conventions have adjusted their purpose. The convention nomination has effectively become ceremonial, culminating in the coronation of a nominee determined during the primary process. With the nominee already determined, another convention function has risen in importance: communicating political commitments to the public — telling a story of America and presenting a vision for America.

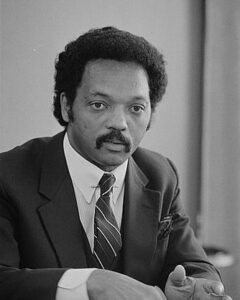

For this reason, I like to have my Government and Politics students read speeches from party conventions over the last 50 years, to see the parties framing and re-framing their vision for America through changing times. Teaching American History’s latest collection, 50 Core American Documents, contains two such keynote speeches: Jesse Jackson’s 1984 “Rainbow Coalition” speech at the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco, and Paul Ryan’s 2012 Republican Vice Presidential Nominee Acceptance speech in Tampa. These speeches offer opportunities for students to see political rhetoric at work — not in any cynical or stereotypical sense of that word, but in the technical sense of persuasive language being employed deliberately in a particular situation. Examining the context and reading the text of these primary sources, students gain instructive lessons in political rhetoric.

While Jackson and Ryan represented different political parties, had different oratorical styles, and spoke to different historical moments, they shared a key contextual similarity. At the time of their respective speeches, both were ascendant political voices representing the “out-party,“ seeking to regain the White House by presenting an alternative political vision. Jackson sought to articulate a vision to revive and expand the momentum of the rights revolutions and social movements of the mid-twentieth century (which he felt was halted and threatened by the Reagan administration) while incorporating it more thoroughly into the Democratic Party coalition. Ryan sought to counteract the policies of the Obama administration, which he argued undermined and threatened the American promise of opportunity and security. While Jackson’s critiques of Reagan were more glancing and stylized, and Ryan’s critiques of Obama were more direct and extended, in both cases we see orators going beyond those critiques in their attempts to call the country back to what they understand to be its highest principles. Reading these speeches in light of their similar contexts offers students a deeper understanding of the factors at play, and a firmer ground to evaluate the speakers’ argumentative choices.

And when you get into those argumentative choices, you find more similarities, even if their approach is, again, different. For example, both speakers strive to connect their alternative, “out-party” visions to the American tradition. Jackson’s vision upheld the project of inclusive and expansive democracy, tracing it through iconic texts like Emma Lazarus’ poem memorialized at the Statue of Liberty, down through the civil rights struggle, the broader activism of the era, and into his present moment. Ryan’s speech attempted to resurrect a vision of American society advanced by prior Republican Party leaders, ideas articulated during the peak of the Reagan Revolution. Both speakers appealed to an image of grassroots, common Americana — Jackson to the “patchwork quilt” of American diversity he wished to embrace as a source of strength and opportunity, and Ryan to entrepreneurial “small businesses,” thriving in “strong communities,” as sources of goodness and hope.

Both speeches also draw inspiration from a then-recently deceased prominent party figure to anchor their themes. These figures are little-known to students today (receiving scant attention in a US History survey), but their political importance weighs heavily on the context of each speech. In his speech, Jackson referenced the ”wisdom, insight and experience” of Hubert Humphrey (1911-1978) as a guide for the party — a fitting invocation, as Humphrey had been a key figure who foregrounded the Democratic Party’s civil rights commitments from the late 40s through the 60s. Indeed, Jackson’s assertion that his “constituency is the desperate, the damned, the disinherited, the disrespected, and the despised” elaborated Humphrey’s famous assertion that government must advocate for those living in the “shadows of life.” Similarly, Ryan drew direct inspiration from the “incredible enthusiasm” of Jack Kemp (1935-2009) — a prominent congressman and central man-of-ideas throughout the Reagan Revolution. In doing so, Ryan wished to draw on the positive disposition of Kemp; Ryan’s statement that “we believe that in every life there is goodness [and] for every person, there is hope” echoed the tone of Kemp, the self-proclaimed “bleeding heart conservative,” and Ryan re-asserted Kemp’s belief that a limited-government vision was the best means of leveraging that goodness and hope for the greater good.

These speeches promoted the “out-party” in their time and reflected resonant ideological visions, but they have faced contests within their coalitions, then and now. Volume editor David Tucker correctly notes that the Democratic Party has adopted many components of the “Rainbow Coalition” vision in its rhetoric over time, but that adoption was neither immediate nor complete. Consider the 1992 DNC, with presidential nominee Bill Clinton’s emphatic economic focus on “expanding [an] entrepreneurial economy of high-wage, high-skilled jobs.” This clearly contrasts with Jackson’s grassroots-oriented focus. While the party did not rebuke Jackson’s vision in the 90s, it placed rhetorical and policy emphasis elsewhere.

Likewise, Tucker notes that the ideas of Ryan’s speech, while once typical, “no longer (and may never again) characterize the [Republican] party.” And yet, even during the decades when this vision held the party’s rhetorical foreground, it also faced contests. A famous convention example came in the 1992 RNC, where Pat Buchanan, intra-party challenger to incumbent president George H.W. Bush, attempted to turn the party’s attention to a “cultural war … for the soul of America” as the Cold War concluded. While we may argue that the Democratic Party has moved more toward Jackson’s vision, and the Republican Party away from Ryan’s vision, these examples show that the process is not neatly linear.

In comparing and contrasting the text and context (immediate and long-term) of these speeches, students have the opportunity to examine the agenda-setting function of political conventions, and to see the strategic storytelling of political rhetoric. And the comparisons merely scratch the surface of what each speech offers individually to a study of American politics — an opportunity to examine the choice diction, historical grounding, and appeal to public sentiment that thoughtful political leaders deploy. By giving students an opportunity to evaluate these contrasting examples of such political rhetoric, we may help them understand more fully the possibilities of political communication.

50 Core American Documents and all our other CDC volumes are available for purchase or download in our bookstore.