Teaching with 50 Core American Docs: John Ross' Address

This is the second post in our series exploring how teachers plan to use our latest CDC volume in their classrooms. West Virginia educator Adena Barnette takes a deep dive into the history surrounding John Ross’ “Address to the People of the United States by the General Council of the Cherokee Nation,” Document 13 in 50 Core American Documents, available for purchase or download in the tah.org bookstore.

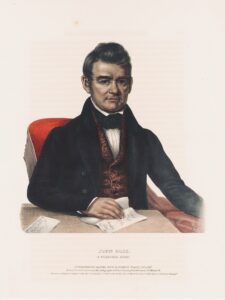

One of the highlights of a history teacher’s summer vacation is attending high-quality professional development that allows a teacher to deep dive into subjects of interest. This summer, I traveled to Reinhardt University in Waleska, Georgia for an NEH Landmarks of American History Workshop entitled “Trail of Tears Context and Perspectives.” Throughout the week, our group visited ancestral Cherokee sites such as the Chieftains Museum/Major Ridge Home and the New Echota State Historic Site. This week long study with anthropologists, historians, and Cherokee elders emphasized the key ideas in Cherokee Principal Chief John Ross’s 1830 “Address to the People of the United States by the General Council of the Cherokee Nation” from the 50 Core American Documents published by Teaching American History (TAH) at Ashland University. I am thankful John Ross’s document is considered one of the top 50 by the scholars at TAH, because what Chief John Ross says about Cherokee sovereignty and his interpretation of American tribal relations harkens back to both the writing of the 1787 U.S. Constitution and the Constitution of the Cherokee Nation, ratified 40 years later by tribal members in 1827. What sovereignty looks like for federally recognized tribal members is still a question that perplexes our Congress, the Supreme Court, and the states. This makes John Ross’s speech a timely and instructive read in American history classrooms. It can help us not only in teaching Native American experience but also in teaching federalism to our students.

The Cherokee before Removal

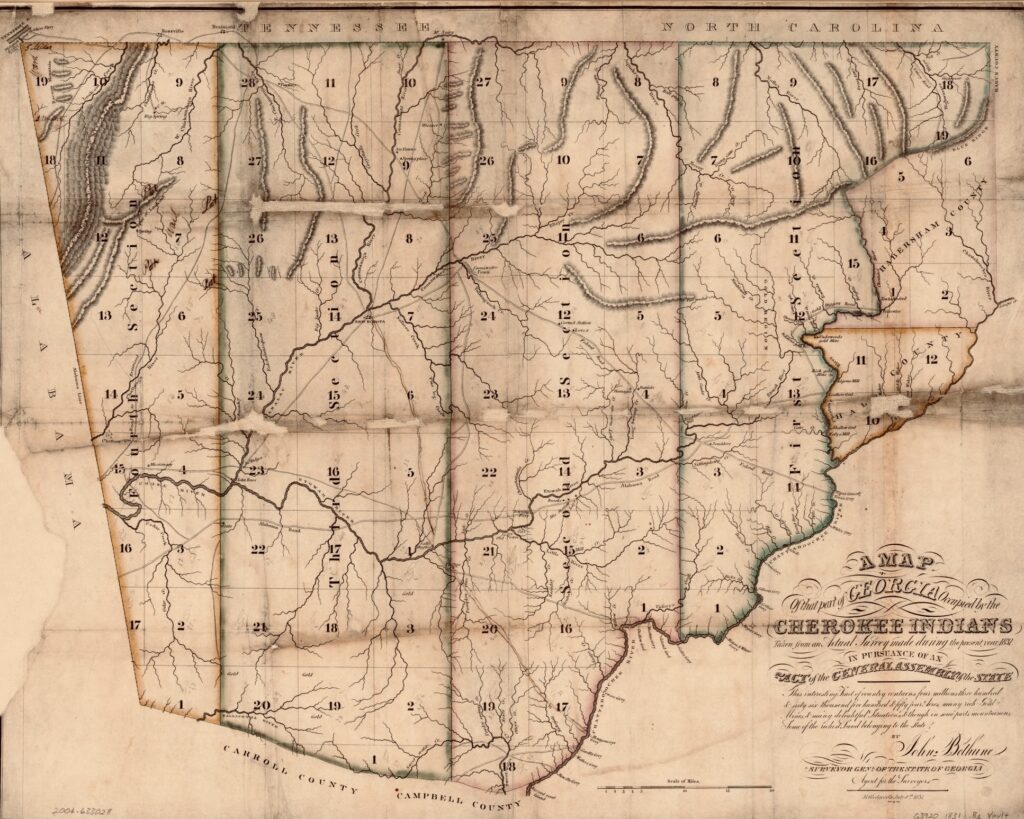

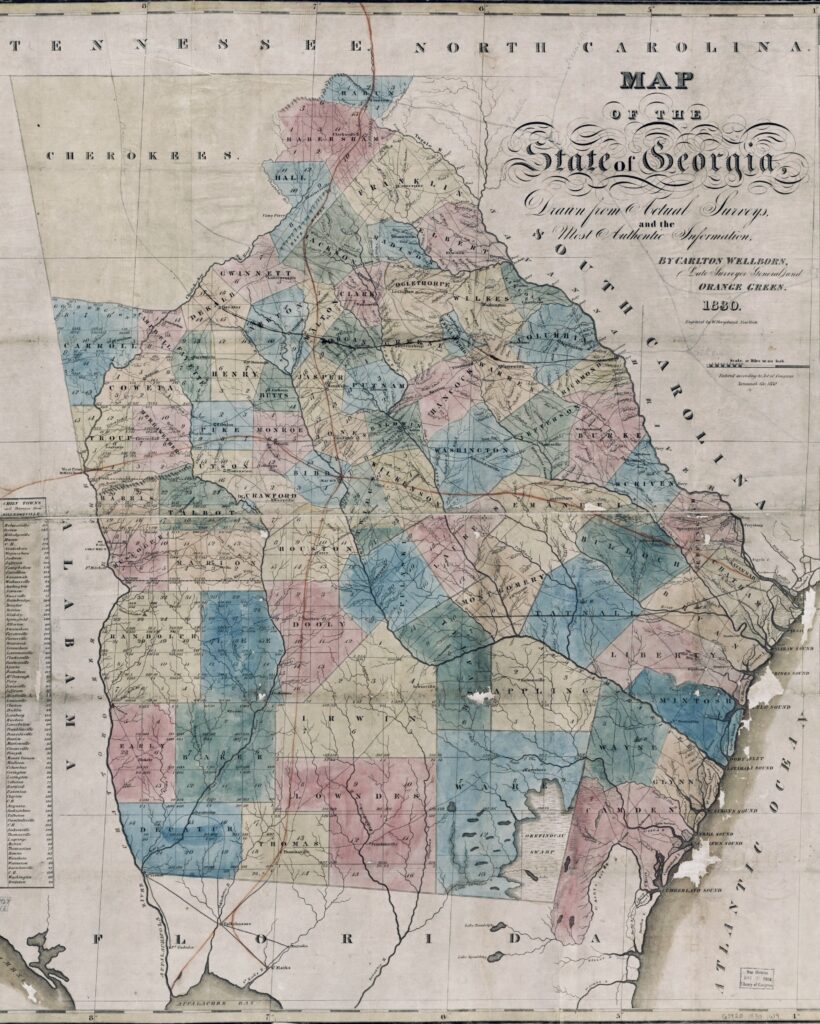

By the time of Chief Ross’s address, the Cherokee had ratified their national constitution, established their National Council, courts, and election system, and were publishing the bilingual Cherokee Phoenix newspaper due to the efforts of Sequoyah (a.k.a George Gist, c.1776 – 1843), the self-taught Cherokee linguist who developed the Cherokee syllabary. While asserting that they were a sovereign nation within the United States, the Cherokee had taken steps towards acculturation. Land grabs, such as those in the 1792 Treaty of Holston, had diminished the range of the Cherokee lands, but the biggest threat to Cherokee sovereignty was the 1828 discovery of gold in northwest Georgia’s mountains. Citizens of Georgia sought to take this land from the Cherokee so they could reap the benefits of America’s first gold rush. By 1832, the state of Georgia set up a land lottery to parcel out Cherokee lands to white Georgians. The whites would assume ownership of those lands once the Cherokees were forced westward.

To understand what was happening amongst the Cherokee and the larger United States, let us look at the key ideas of John Ross’s address, ideas that were explored in depth in the NEH workshop.

John Ross’s Address

Idea #1: Cherokees were acculturated under the American Indian Policy established by President George Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox.

John Ross states that:

. . . the Cherokees looked upon the promises of the whites with great distrust and suspicion; but the frank and magnanimous conduct of General Washington did much to allay these feelings. . . . To this result the aid which we received from the United States in the attempts of our people to become civilized, and the kind efforts of benevolent societies have greatly contributed.

These “civilization efforts” included teaching Eurocentric agricultural practices such as keeping penned livestock animals and male tribal members taking the lead in the planting of crops. Women were taught home industrial practices such as spinning and weaving. Benevolent societies, such as the Moravian Mission at Springplace, Georgia, were invited into the Cherokee nation to teach children.

Idea #2: The Cherokee nation is a sovereign nation with its own government, laws, and constitution.

At the heart of John Ross’s address is his insistence that even after the American Revolution, during which the Cherokee sided with Great Britain, the Cherokee were a free and independent people. As Ross explains, the Treaty of Holston was negotiated with the U.S. Government in 1792, after the U.S. Constitution had been adopted, and that:

The Cherokees acknowledged themselves to be under the protection of the United States, and of no other sovereign. They engaged that they would not hold any treaty with a foreign power, with any separate state of the Union, or with individuals. They agreed that the United States should have the exclusive right of regulating their trade; that the citizens of the United States have a right of way in one direction through the Cherokee country; and that if an Indian should do injury to a citizen of the United States, he should be delivered up to be tried and punished. A cession of lands was also made to the United States. On the other hand, the United States paid a sum of money; offered protection; engaged to punish citizens of the United States who should do any injury to the Cherokees; abandoned white settlers on Cherokee lands to the discretion of the Cherokees, stipulated that white men should not hunt on these lands, nor even enter the country without a passport; and gave a solemn guaranty of all Cherokees lands not ceded. This treaty is the basis of all subsequent compacts; and in none of them are the relations of the parties at all changed. The Cherokees have always fulfilled their engagements.

John Ross is simply stating that the treaties have not been altered and therefore Cherokee sovereignty has not changed.

Idea #3: The U.S Constitution’s Commerce Clause (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3) asserts Congressional regulatory authority over Native American Tribes.

John Ross states in his address that:

More than a year ago we were officially given to understand by the secretary of war that the president could not protect us against the laws of Georgia. This information was entirely unexpected; as it went upon the principle that treaties made between the United States and the Cherokee Nation have no power to withstand the legislation of separate states; and of course, that they have no efficacy whatever, but leave our people to the mercy of the neighboring whites, whose supposed interests would be promoted by our expulsion or extermination.

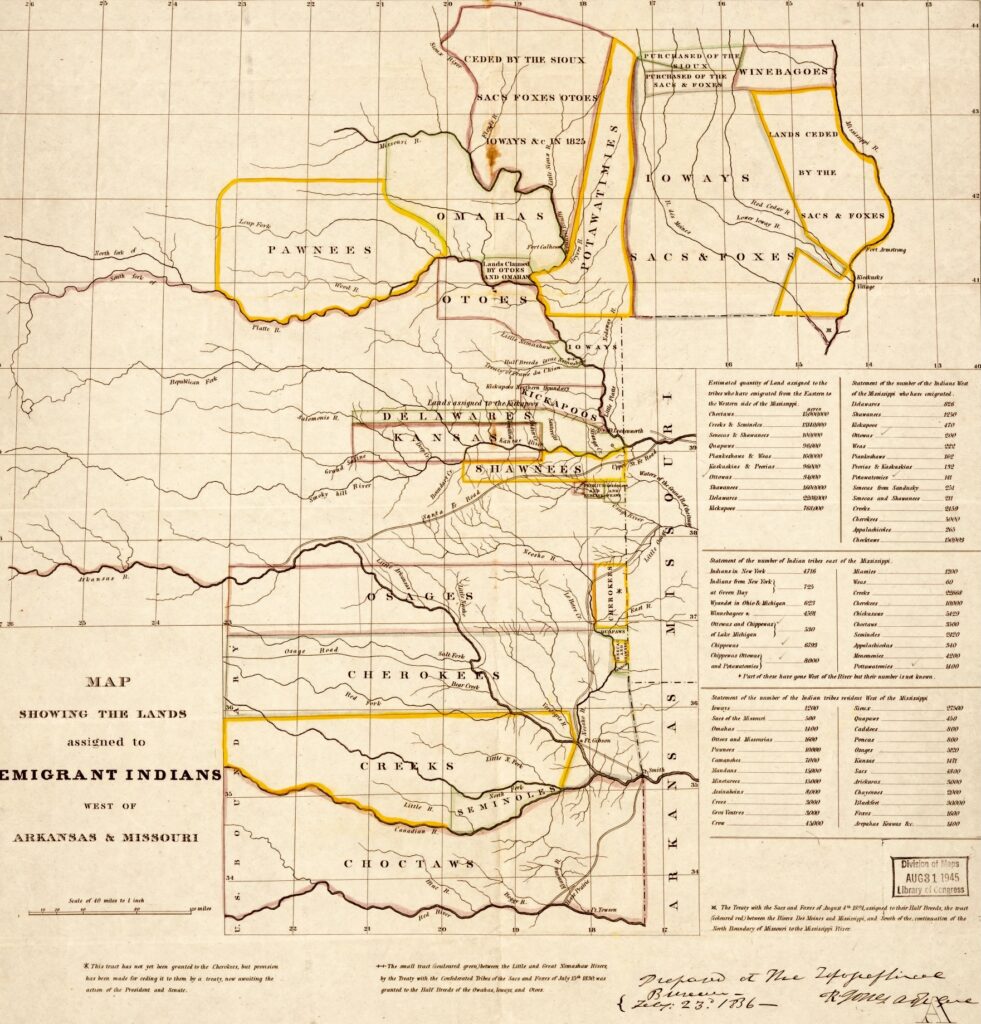

Georgians were already moving into Cherokee lands, and President Andrew Jackson’s failure to protect the Cherokee from the actions of the Georgians was in direct conflict with the U.S. Constitution’s supremacy clause (Article VI, paragraph 2). Ross, aware of this, goes on to say that “But it never occurred to us for a moment that without any new treaty, without any assent of our rulers and people, without even a pretended compact, and against our vehement and unanimous protestations, we should be delivered over to the discretion of those who had declared by a legislative act that they wanted the Cherokee lands and would have them.” However, President Jackson had pushed through Congress a bill that ignored the nation’s treaty obligations to the Cherokee. This was the Indian Removal Act, passed on May 28, 1830, which authorized the president to renegotiate the earlier treaty. In effect, Congress overrode the earlier treaty, while asserting its regulatory authority, per the commerce clause, over relations with the Native American tribes.

A suit brought by a Christian missionary, Samuel Worchester, who resided in the Cherokee nation became the 1832 Supreme Court case Worcester v. Georgia. Worcester challenged the president’s Constitutional interpretation. Chief Justice John Marshall stated in the majority opinion, “The Cherokee nation . . . is a distinct community occupying its own territory in which the laws of Georgia can have no force. The whole intercourse between the United States and this nation, is, by our constitution and laws, vested in the government of the United States.” The effect of the ruling, however, was merely to restrain white residents of Georgia from moving into Cherokee lands before the federal government carried out the removal efforts authorized by the 1830 act.

Idea #4: Most of the Cherokee opposed any Indian Removal Efforts.

John Ross also declares that the Cherokee “are not willing to remove” and that they:

. . . wish to remain on the land of our fathers. We have a perfect and original right to claim without interruption or molestation. The treaties with us, and laws of the United States made in pursuance of treaties, guaranty our residence, and our privileges and secure us against intruders. Our only request is that these treaties may be fulfilled, and these laws executed.”

Most Cherokees sided with Ross in resisting removal. Like him, they wanted to remain and die on “the land which gave us birth.” Yet a small faction saw removal to the future state of Oklahoma as the only solution to the violence committed by Georgia whites over Cherokee lands. This group signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835, without the advice or consent of the Cherokee National Council. This clandestine effort granted the United States government the power to remove the Cherokee through military force onto the Trail of Tears. Over 4000 tribe members lost their lives on this journey during the winter of 1838-1839. Once the Cherokees arrived in Oklahoma, they rebuilt their familial bands, communities, and their sovereign tribal government; they are now the largest federally recognized tribe in the United States with over 430,000 members. John Ross’s speech is requisite reading to understand an early example of the U.S. Government’s long and troubled relations with America’s sovereign tribes. A forthcoming volume in the core documents series, Native Americans, explores this and other issues in depth.

Adena Barnette-Miller began teaching in 2003 and graduated from the Ashland MAHG program in 2014. She was the 2011 James Madison Fellow for West Virginia and was the 2021 Gilder-Lehrman’s West Virginia History Teacher of the Year. She is the president-elect of the West Virginia Council of the Social Studies.