50 Core American Documents: An Interview with the Editor, David Tucker

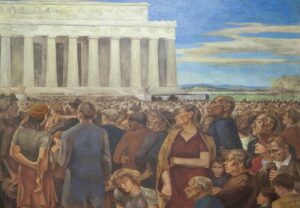

Teaching American History is proud to present our latest Core Document Collection volume, the second edition of 50 Core American Documents. Redesigned to bring the collection into the 21st century, 50 Core American Documents provides educators and students with a collection of primary source documents chosen specifically for the secondary social studies classroom.

50 Core American Documents is available in our bookstore as both a paperback and ebook. Discounts are available for educators who are interested in purchasing a class set. Please email [email protected] for more information.

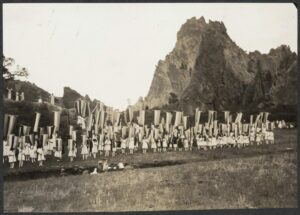

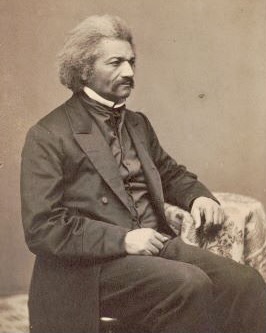

1. Some of the documents in this collection are classics. Federalist 10, Frederick Douglass’s “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”—we expect to find those here. But others are much less well-known: for example, W. B. T. Williams’ “The Negro Exodus from the South” or “Plenty Horses Kills Lieutenant Casey.” How did you decide which among the 2500 documents in our online library to include in this volume?

We have a very rich heritage of primary sources documenting our history. It would have been possible to put together a good collection made up of fifty documents that did not make it into this anthology. I tried to collect documents that could, in a short space, encapsulate the key ideas, incidents, and developments in the American experiment of self-government. To this end, I included many that are often read, but also some seldom read documents that should be better known. In fact, a few of the documents included here are entering our online library for the very first time.

You mention Williams’ account of the Great Migration of African Americans who began leaving the South in large numbers during the first World War. I don’t remember how I came across this, but it gives a fascinating account of the migration, written by someone working for the Department of Labor. He was a black researcher who traveled throughout the south, talking to both black and white citizens about the exodus of black laborers. Black people tell him they are fleeing Jim Crow restrictions on their freedom and job opportunities. While a few white people admit that racial injustice is a serious problem in the south, most whites profess not to understand why blacks are leaving.

The research was prompted by concerns that growing populations of African Americans in American cities where defense industries were located would cause problems with white workers. The government also worried about the departure of black labor from the south, an area that was still predominately agricultural and relied on black labor. Williams was tasked to answer the question, “how can we keep black people in the south?” What he conveys in an understated way—I assume he was concerned that he was going to offend people—is that the answer is simple: “they will stay if whites stop abusing them.” The migration was important and this a contemporaneous account by a black man, so I wanted to include it.

2. I was surprised by the very first document in the collection: an excerpt of Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography.

Knowing my admiration for Franklin, you were surprised? Listen: although this opinion may be heretical, I think Franklin is one of the two most important figures in the American founding—the other being Thomas Jefferson, of course. Franklin is a problematic candidate for this honor, because he was a late convert to independence; yet his life embodied all that was new and distinctive about America. Franklin indirectly compares himself to Socrates and Jesus, who invented entirely new ways of being human, yet never themselves wrote about their innovations. Franklin invented a new way of life and wrote about it, in very memorable language.

He is the seventh son of a seventh son; he began life without any particular advantages. It’s only through remarkable discipline that he succeeds. While his co-workers break for a lunch washed down with beer, he eats a sardine and crust of bread while reading a book he’s acquired through his frugality. Yet he knows his autobiography will be read by ordinary Americans who lack his talents and virtues, so he writes the first self-help book, telling his fellow citizens how to lead a happy life. I’m a big fan of Franklin, and I think we ought to read and study him more seriously than most of us do

3. I see what you mean—in suggesting that anyone who tries can achieve happiness and success, Franklin introduces a theme that runs throughout this collection: the “self-evident” truth of human equality. In your introduction to the volume, you say this theme is the transcendent cause of all the other documents. Yet you also say that no idea in American history has been so hard for Americans to understand or has caused them so much trouble.

Are you saying I contradict myself? Equality has been an extremely difficult concept because it’s transcendent. It is the alpha and omega of our political system. Those who have attacked the founders’ idea of human equality—John Calhoun, for example, whose speech on the Oregon Bill is Document 19 in the collection—say, in effect, that people are not born equal. They are born as helpless infants, dependent on the adults and families in which they are raised. They attain independence only to the extent that their intellect and physical powers are developed. And the theoretical “state of nature” of which enlightenment thinkers spoke never existed. There has always been society, and society has always been divided into ranks and castes with different economic and social statuses. Calhoun took the idea of equality literally. But in its transcendent meaning, human equality applies to our moral relation to one another. In this sense we are all equal, because we all belong to the same species. As Madison says in his “Memorial and Remonstrance” (Document 6), every person has a duty to worship God in the way that his reason teaches him is best. But no one has a duty to worship another man. The divinely sanctioned rule of kings is over. Lincoln said in his Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise (Document 22),”no man is good enough to rule another man, without that other’s consent.”

In the same speech, Lincoln makes clear the moral reality of human equality by talking about how even slaveowners show that they know the slaves are enslaved human beings. They don’t like to deal with slave buyers. They let their children play with the children of slaves, but they won’t let their children play with the children of slave buyers. And Lincoln says they don’t react that way to people who buy their corn or tobacco.

The moral equality of all people leads logically to our representational system of self-government, in which citizens renew their consent to be governed at every election. It leads to all the checks and balances in our Constitutional system, all designed to prevent any group of people from tyrannizing over any other. But government by the consent of our fellow human beings means that to some degree we are ruled by ignorance and prejudice, because that is part of being human. So we have to overcome that, we have to work to achieve equality or justice.

4. This points to another theme that runs throughout much of the volume: the idea of progress.

Without a doubt, the founders understood their experiment in self-government a step forward in human progress. Later Americans saw it the same way. John Quincy Adams in his Address . . . Celebrating the Declaration of Independence (Document 12) called our constitutional system the first legitimate government in the history of mankind, an achievement that “must forever stand alone.” Adams argued that the great milestones in human history were Jesus, the Protestant Reformation, and the American Revolution. Christianity is itself a revolutionary force, and the Reformation, Adams said, gave greater evidence of progress than technological advances did. That was because the Reformation empowered human beings to deal directly with their creator, without the mediation of priests. It granted every man the “right to the exercise of his own reason.” That’s another dimension of the idea of equality. There are a number of documents in the collection that track the religious aspect of the ideas of equality and progress. In fact, if you think about progressive politics today, and its championing of the least advantaged—well, that shows the influence of Christianity, even though many progressives today would not call themselves Christian.

5. Yet it seems Americans have defined progress in very different ways. Franklin seemed to suggest that human progress depends on individual efforts. Woodrow Wilson seemed to say it depends on the agency of the state—on the expertise that government can gather and bring to bear on human problems.

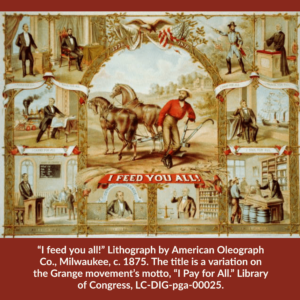

Yes, this is an important theme that emerges after the Civil War. Beginning with the Farmers’ Movement (Document 26), a number of documents in the collection discuss the inequalities developing because of industrialization and the concentration of wealth. Americans struggle with this, realizing that, if we are really taking the Declaration seriously, we have to deal with these problems. The volume also includes some documents from the civil rights movement and the women’s rights movement. And a Supreme Court case from 2003, which shows the justices struggling with questions of equality and justice.

6. I was interested to see an excerpt from the report of the McGovern-Fraser commission (1971) in the collection. That commission is fairly obscure. Why did you include that excerpt?

Our master’s program is a program in history and government. We have document collections on the political parties, Congress, the presidency, and the judiciary and we have others in the works on the separation of powers and federalism. Working on the document collections that faculty like Joe Postell, Eric Sands, Jeremy Bailey and Josh Dunn have done, I have read a lot of very useful, very informative documents, so I wanted to make sure some of that got in the book. As the introduction to the report of the McGovern-Fraser commission explains, the reforms that the commission proposed have a lot to do with the current system we have of electing the president. There are a couple of other documents toward the end of the collection that also help explain aspects of our current politics.

Pick up your copy of 50 Core American Documents today!