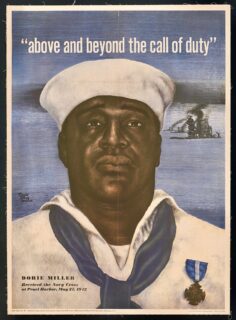

A Black Sailor's Heroism at Pearl Harbor

For the eightieth anniversary of Pearl Harbor Day, we’re recalling a poem by Gwendolyn Brooks, “Negro Hero.” Brooks gave the poem a subtitle: “to suggest Dorie Miller.” She wrote it in part to commemorate this black sailor, whose swift and heroic response to the sudden attack on Pearl Harbor saved many lives. Published in 1945, her poem also captures the ironic relationship between thousands of black American servicemen and the democracy they defended during World War II, a democracy that at the end of the war still denied them full civil rights.

A Poet Gives Ironic Voice to Miller’s Service

Brooks’ poem speaks in the voice of a hero recounting his bold and decisive actions amid the chaos of the sudden attack. Miller’s service at Pearl Harbor included pulling wounded white sailors to safety in the watery wreckage of a sinking ship, the US West Virginia. Recalling that day, the narrator begins,

I had to kick their law into their teeth in order to save them.

However I have heard that sometimes you have to deal

Devilishly with drowning men in order to swim them to shore.

Or they will haul themselves and you to the trash and the fish beneath.

(When I think of this, I do not worry about a few Chipped teeth.)

Miller not only carried fellow sailors—including the ship’s dying captain—out of the line of fire. He took control of an antiaircraft gun he’d been ordered to load with ammunition, a weapon he’d never been taught to use, and began firing on incoming Japanese bombers. He’s credited with downing two of them.

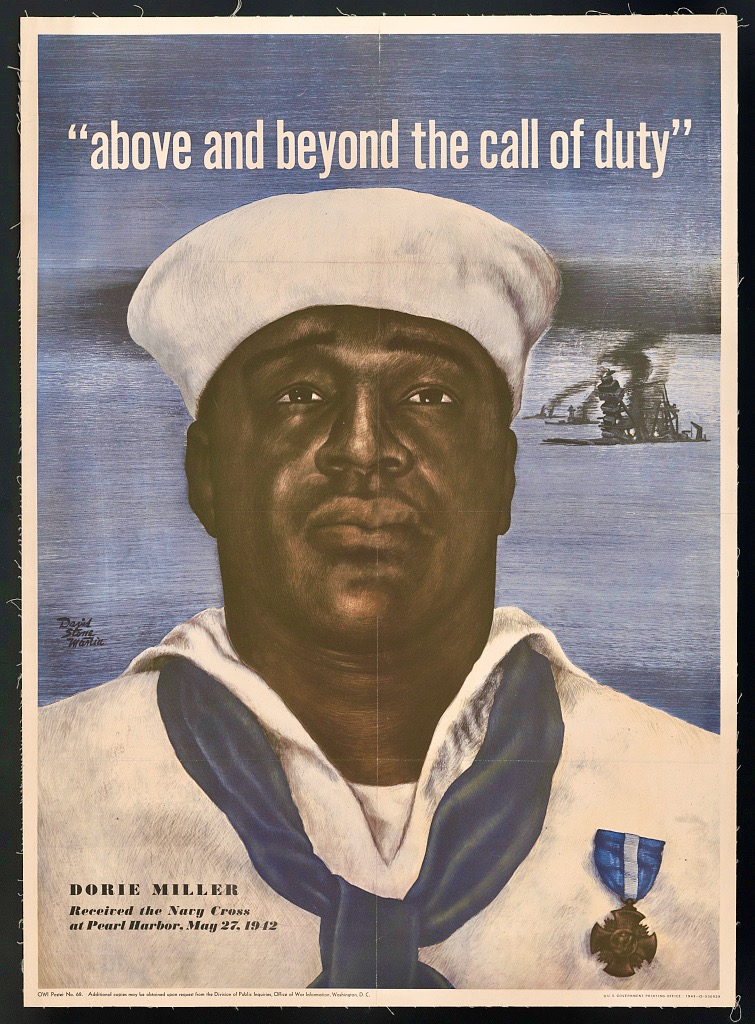

The narrator of the poem looks back on this heroism and asks, “am I good enough to die for them, is my blood bright enough to be spilled . . . . Or do I intrude even now?” In a list the Navy published January 1, 1942 of those to be commended for their actions at Pearl Harbor, an unnamed black sailor was mentioned. Persistent inquiries from the African-American newspaper the Pittsburgh Courier uncovered Miller’s identity. In May, Admiral Nimitz awarded Miller the Navy Cross (not the Medal of Honor that a New York senator and a Michigan congressman had asked their colleagues in Congress to award the sailor from Waco, Texas).

When Miller was killed two years later—in the Battle of Makin, while serving aboard the Liscome Bay—he had attained the rank of Cook Third Class. Like 1.2 million other black men who fought in the war, he was relegated to support positions, sleeping in segregated quarters, throughout his service.

A Complex Set of Motives

The narrator offers three explanations of his bravery. When the bombing began, he sprang into action with a warrior’s instinct, “my blood . . . Boiling about in my head and straining and howling and singing me on.” He also makes clear that in calmer moments, he saw himself fighting not against the enemy Japanese but against the racism of a country that denied his equality. When his photograph appeared in the national papers, he says, white readers missed the fact that “it was hardly The Enemy my / fight was against / But them.”

Then the narrator admits a motive beyond bitterness. His heroism, he says,

. . . was kinder than that, though, and I showed like a banner

my kindness.

I loved. And a man will guard when he loves.

Their white-gowned democracy was my fair lady.

With her knife lying cold, straight, in the softness of her

sweet-flowing sleeve. But for the sake of the dear smiling mouth and the stuttered

promise I toyed with my life.

Students who read this poem will find much to discuss in the image of Lady Liberty with a knife hidden in her sleeve. Brooks gives us the black soldier’s heroism in all its ambivalence: a compound of self-sacrifice for a cherished ideal, pride in his accomplishment, and accusation against those who denied him dignity and recognition.

Last year, the Navy gave overdue honor to Miller. It began building a supercarrier, the U. S. S. Dorie Miller, scheduled to be commissioned in 2032.