Helping All Students Learn US History

“I don’t teach AP classes. And I’m happy I don’t,” says New Jersey high school teacher David Glass. “My students don’t work to get a grade. They just want to understand our history.”

Glass teaches US History I and II, as well as a one-semester elective in Holocaust and Genocide, at Parsippany High School. He works with co-teachers trained in special education. Approximately half of his students have IEPs (Individualized Education Plans). Some of his students struggle with intellectual disabilities, others with social, emotional, or medical differences. Working with co-teachers, Glass can help all his students.

The co-teachers are certified in history as well as special education. Glass himself has learned special education strategies from the teachers he partners with. “Sometimes I work with the special ed students, while the co-teacher works with the regular level students. Lately I’ve found that my students with autism look to me as an older father figure, and seem more responsive to me.”

Meeting students’ needs does not mean simplifying the coursework. Special needs students are “not excused” from learning history. “They need to learn it.” Like other students, they will learn more by reading primary documents. “I stopped using a textbook years ago,” Glass says. Textbooks “glossed over things that deserved more time, and spent time on things that nobody cares about. I could find better resources online.” Glass uses primary documents available on websites such as TeachingAmericanHistory.org.

Primary sources give students direct access to the experience of those who lived in the past. They are not filtered through the opinions of textbook authors or the sensitivities of state education officials. They are “real,” Glass says.

TAH Seminar Offers New Primary Sources and Perspectives

In October, Glass traveled to San Diego for a TAH weekend seminar on “Race and Religion in American Politics,” led by Professor Gaston Espinosa of Claremont McKenna College. The seminar reacquainted Glass with Malcolm X’s autobiography, which he read thirty years ago, while serving in the Navy. “It was great for me to get back into it and understand it better than I did then,” Glass said. Espinosa also helped Glass see the theological perspectives that informed texts like Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Now, he can bring that perspective into his classroom.

Beyond these insights into the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, Glass learned about reform movements among “Mexican Americans in the southwest and migrant workers in California.” Glass hadn’t known that Cesar Chavez embarrassed the Catholic Church hierarchy into backing the farmworkers’ labor movement by pointing out the support Protestant groups were offering. He also learned about the American Indian Movement. Active in the Pacific Northwest, this movement is far from the radar of teachers working on the east coast.

“I’ll bring sources on those things to my classroom,” Glass said.

Helping Special Needs Students Read Primary Documents

“The documents we read at the seminar were great,” Glass said. “But when I take them to my students, I will need to break them down into smaller bites. Some, I will need to annotate.”

Every year, on the first day of school, Glass presents his US History I students with a three-page excerpt from Bartolomé de Las Casas’s Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. He hands it out, saying, “Read that, and tell me what it says.” The students stare in bewilderment at the pages in their hands.

Then Glass says, “Wait. You hold on to that, but let me give you something else.” He distributes copies of the excerpt broken down into “four parts with a graphic organizer and some vocabulary definitions.” The handout includes spaces for students’ notes. Glass explains how students will work through the document: “The first part we’ll do together. The next one you’re going to do with a group. The third you’ll do with a partner. And the last one you’ll do by yourself.”

This process teaches students a coping skill. When they’ve completed the study of Las Casas, Glass asks them to pull out the three-page text he originally gave them. “I say, ‘Really? Was it that overwhelming?’” The next time he assigns a primary document, Glass says, “Remember when we did the first reading? We broke it down and read it slowly.”

Students repeat this reading process as they move forward in history. Glass may drop one or more steps as the primary documents he uses become more modern and as students become more confident.

The Fundamental Importance of the Constitutional System

He provides lots of scaffolding as students work through foundational documents. He spends the second marking period—two and a half months—on the Declaration, the Articles of Confederation, the Constitutional Convention, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, concluding with the peaceful transfer of power between Adams and Jefferson in 1800. This helps students’ understand the American constitutional system as a strong framework for a country that remains “a work in progress.”

At the beginning of the year Glass explains to students, “You’re in high school now. It’s not that we haven’t been telling you the truth about our country. But you need to know all the truth. It’s not always nice. You’re going to learn things that you’ll be upset about. You’ll wonder why your country did that.

“But we were strong enough, and our constitution was strong enough, to make changes that made things better,” Glass says. “Did we put Japanese Americans in concentration camps? Yeah, we did. Thank God that when we were bombed on 9/11, we didn’t put Muslims in a concentration camp. I’m sure there were people ready to do that”—but in that instance our constitutional system worked to prevent it. “If you object to what is happening in America,” Glass tells students, “you have to find a way to change it.”

The Most Important Lessons

Although no longer shocked, Glass remains bemused when students do not understand that “we are the government. It’s government of the people by the people, and for the people.” In his US History II class, when Glass talks about Theodore Roosevelt’s land conservation efforts, he asks, “‘Whose land is it?’ Students reply, ‘It’s the government’s.’ I say, ‘No, it’s yours.’”

He underscores the concept of all people’s inherent natural rights. “The government isn’t here to grant you rights. You have the rights. They’re just helping you make sure nobody takes them away from you.” Grasping this, students realize their responsibility to participate in government through voting and other activism.

Beyond this responsibility, what does Glass most hope to teach? “How to be a nice person,” he answers. “I want students to be successful. They don’t need to get an A, but they do need to know how to get along. Doors open for people like that.

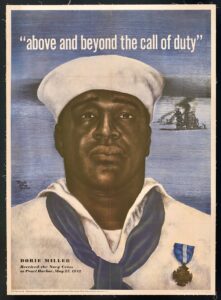

“I tell them, ‘I want to get you out of here knowing what’s right and what’s wrong. Making other people sit in the back of the bus is wrong. Being kind to people, putting yourself in their shoes and asking, ‘Would you want to be treated that way?’—that’s the golden rule, and the most important lesson,” Glass says.