MAHG's Importance to Ginny Boles

Ginny Boles needed to build her content knowledge in American history. Paradoxically, her love of this history had led her to major in classics as an undergraduate at UCLA, so as to read the Latin and Greek texts the Founding Fathers read as they formulated their plans for self-government. Now, having taught social studies for two years at Oakcrest School in Vienna, Virginia—an independent girls’ school in the Catholic tradition—she knew what she didn’t know. She needed more knowledge to answer students’ questions. She hoped to study part-time while continuing to teach.

Living in Northern Virginia, she thought she had options. George Washington University, Georgetown, American University, and even the University of Virginia offer Masters programs on campuses in the District of Columbia. Investigating them, she discovered what is true of most MA programs in history: the courses were scheduled during her teaching day, and the curriculum emphasized methodology, to prepare students for PhD research.

Boles had hoped for in-depth seminar discussions on the eras of history she’d never studied. Discouraged, she almost enrolled in Gilder Lehrman’s program, which is built primarily around recorded online lectures by prominent scholars. “But they paused the program, right when I was ready to start, so I was left without any good option.”

A Program Designed for Working Teachers

Then, in the same week, two different people told her about the Master of Arts in American History and Government program (MAHG). A teacher friend in Pittsburgh came back from a week in the summer residential MAHG program, having audited a course on Lincoln. “This seminar I just took was amazing,” the friend said. “It’s at Ashland University, and they offer a Masters.” Next, her father called. After a busy career in law, he had reduced his practice and taken up teaching history at the high school Boles graduated from in Pasadena, California. He’d just returned from a multi-day Teaching American History seminar at the Reagan Library, led by Professor John Moser. “This organization offers amazing professional development!” he said. “They also offer a Masters, at Ashland University.”

“Then I got on Ashland’s website,” Boles said. “As soon as I read about MAHG, I realized, ‘This is designed for me! And it’s been the best experience ever. I recommend it to any history teacher I know who’s looking for a Masters.”

She has enjoyed both the online and on-campus experience. “MAHG’s WebEx seminars pretty well simulate in-person seminar classes. But I loved going to Ashland and seeing people I had ‘met’ on the screen. You could bond over having been with someone for those WebEx sessions.”

She has also enjoyed the hours of private study. “I love being able to say: ‘Oh, sorry. I have to go do my reading right now.’” The readings fascinate her, and they have changed her teaching.

How MAHG Builds Content Knowledge and Confidence

“My first two years teaching American history were fun, but a little bit rough. I was like every new teacher tackling a new course, barely learning enough at night to teach it the next day. Then one of my high school juniors would raise a hand and ask a good question. I had to say: “I don’t know. I’ll check and get back to you.” But there was never time to research extra things!”

After several MAHG courses, she found she had answers. “Last year, my students were asking questions about the daily experience of enslaved people and the attitudes of slaveholders. I could say, ‘I’ve read these letters and memoirs. I think I can answer that.’ I became a lot more knowledgeable and more confident.”

Beginning the program, she lacked the content knowledge of many of her classmates, who had taught for years in public schools. These veteran teachers “are inspiring me to learn more and teach better.”

Learning through Text-Based Discussions

At the time, Boles used primary source documents to a limited extent. This was not for lack of a model in teaching students how to read and discuss texts carefully. She began her teaching career at the Geneva School in Manhattan, where she taught the “great books” of Latin using a simple but effective approach called “Shared Inquiry” (The method was pioneered at St. John’s University and elaborated by the University of Chicago). She found that most MAHG professors applied a similar approach to primary documents. “MAHG classes are discussions grounded in texts.” The professor poses a question based on a document all have read. Teachers respond, using the text as evidence. Anyone offering an opinion based on their own experience or prior beliefs is reminded, “where in the text do you find support for that?”

Seminars conducted in this way teach “how to disagree with others civilly.” Since everyone shares the same piece of evidence, there are no arguments about unverifiable claims. Reading speeches, essays and letters on contrasting sides of a political issue of the past, MAHG students think through the logic of each perspective together. Students learn to “listen closely, responding in their comments to what the person before them said.” MAHG professors clarify confusing points—but “their own politics doesn’t enter the discussion.”

Two years into the MAHG program, Boles began to add more primary source documents to her courses. She now understood which documents illuminated the themes in history she most wanted to teach.

MAHG Helps Teachers Define Their Priorities

By then, the MAHG program had helped Boles define her teaching priorities. MAHG faculty, drawn from universities across the country, are about equally divided between historians and political theorists. The dual perspectives benefit both history and government teachers. “I didn’t really know the difference between the two when I began MAHG,” Boles said. I asked my professors, and they explained it to me.” While she took some “super helpful” courses from historians who emphasized social history, she discovered that she was most drawn to political theory.

In Boles’ judgement, all Americans need to ponder two questions: “‘What is the role of government? And, ‘What is required to create—and then sustain—a free republican government?’ This has become my ‘essential question’ for all the courses I teach, whether it’s sixth grade Ancient History, 11th grade American History or 12th grade Government and Modern World History.”

Boles does not teach AP courses at Oakcrest; she teaches students more inclined to take AP courses in math and science. Without the pressure to cover everything that might appear on the AP exam, she can choose events and topics centered on her theme. The first part of her American history course covers the development of self-governing traditions in the colonial period; the Revolution; the first framework for national government, the Articles of Confederation; and the lasting framework developed at the Constitutional Convention.

Little-Known Documents that Illuminate Big Issues

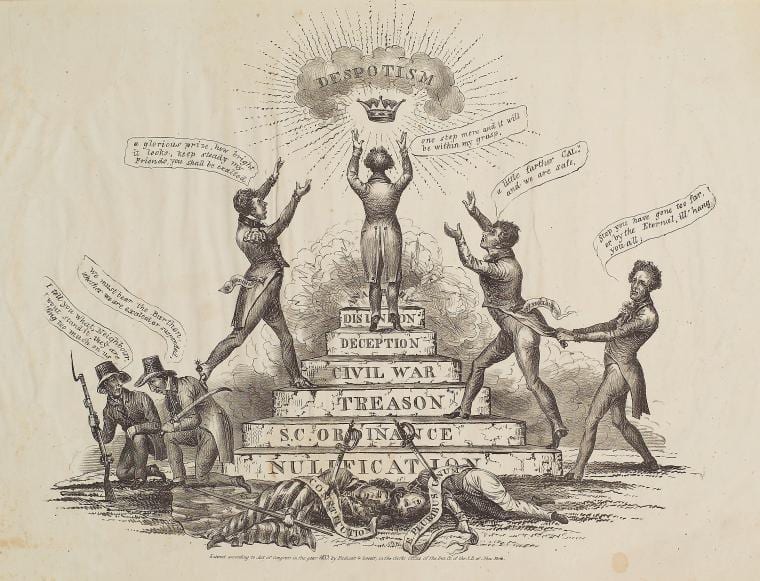

Then she moves to the controversy over “nullification.” Americans rebelled against the tyranny of George III, and after winning independence worked to create a government that would not fall back into tyranny. But by 1830, some complained that a tyrannous northern majority were imposing tariffs on a southern minority. Boles assigns excerpts of the debates between Senator Daniel Webster (MA) and Senator Robert Hayne (SC); Andrew Jackson’s 1832 proclamation repudiating South Carolina’s Ordinance of Nullification; and an exchange of letters between Hayne and the elderly James Madison, who’d written the 1798 Virginia Resolutions in response to the Alien and Sedition Acts. Madison had claimed the right of a state to “interpose” when Congress overstepped its Constitutional authority.

“Hayne sent his speeches to Madison,” asking him to confirm his arguments in favor of states’ rights. “Madison’s letter back says, ‘You’re completely wrong.’” Students discuss whether Madison’s thinking on state sovereignty and federal authority changed, or Haynes’ and John C. Calhoun’s opinions diverged from the founder’s position. “I love this exchange—and I learned of it through MAHG,” Boles says.

Having considered “the nature of the union” apart from “the obvious moral element of slavery,” Boles’ students see the states’ rights claims made by slave-holding secessionists at the outset of the Civil War with greater clarity. “Lincoln’s First Inaugural takes on”—and demolishes, Boles says, “every single argument the secessionists make.” Later, she presents the Progressive challenge to constitutional provisions “that the founders saw as protections against tyranny. The Progressives had a completely different view of government’s role.”

Thesis Work that Answers Important Questions

To complete her degree requirements for MAHG, Boles is writing a thesis. (Many MAHG students opt instead to take four more course credits, for a total of thirty-two, and a cumulative exam.) The MAHG program invites teachers to write on the questions they most need to answer. Boles will write on the Progressive critique of the founding. “Did the founders establish a government that protects only individualism? Or did they see their limited government taking care of the common good?”

“Everything we’re asked to do in MAHG can be transferred to my teaching,” Boles says. “It’s demanding but doable for someone teaching full time. It is also really fun!”

2022 Summer MAHG Enrollment

There are still spots available for on-campus MAHG classes this summer. Join us for any of the following:

- Law and Literature (HIST/POLSC 680 2HLB): A study of the connection between American literature and law through both fiction and non-fiction, including The Crucible, Billy Budd, To Kill a Mockingbird, and Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption. These primary texts will be supplemented with primary historical documents, including, for example, sermons from Puritan New England alongside a study of McCarthyism for the Crucible, and documents related to Civil Rights for To Kill a Mockingbird.

- Age of Enterprise (HIST/POLSC 605 4A): In the last decades of the 19th century, the United States took decisive steps away from its rural, agrarian past toward its industrial future, assuming its place among world powers. This course examines that movement, covering such topics as business-labor relations, political corruption, immigration, imperialism, the New South, and segregation and racism.

- The Progressive Era (HIST/POLSC 505 4A): The transition to an industrial economy posed many problems for the United States. This course examines those problems and the responses to them that came to be known as progressivism. The course includes the study of World War I as a manifestation of progressive principles. The course emphasizes the political thought of Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and their political expression of progressive principles.

Registration information can be found here.