Common Sense: The Book of the Year (in 1776)

It’s a pattern familiar to most Americans. Various media sources publish “best books of the year” each December, accompanied by a preview of books scheduled for release in the new year. Although several political books hit the non-fiction best-seller list in 2022, none delivered the impact a 46-page pamphlet did when it was published early in the American Revolutionary War. It is a safe bet that no book published in 2023 will do so, either.

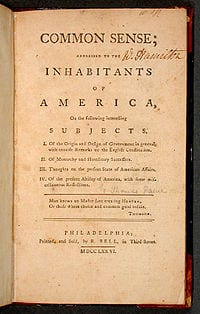

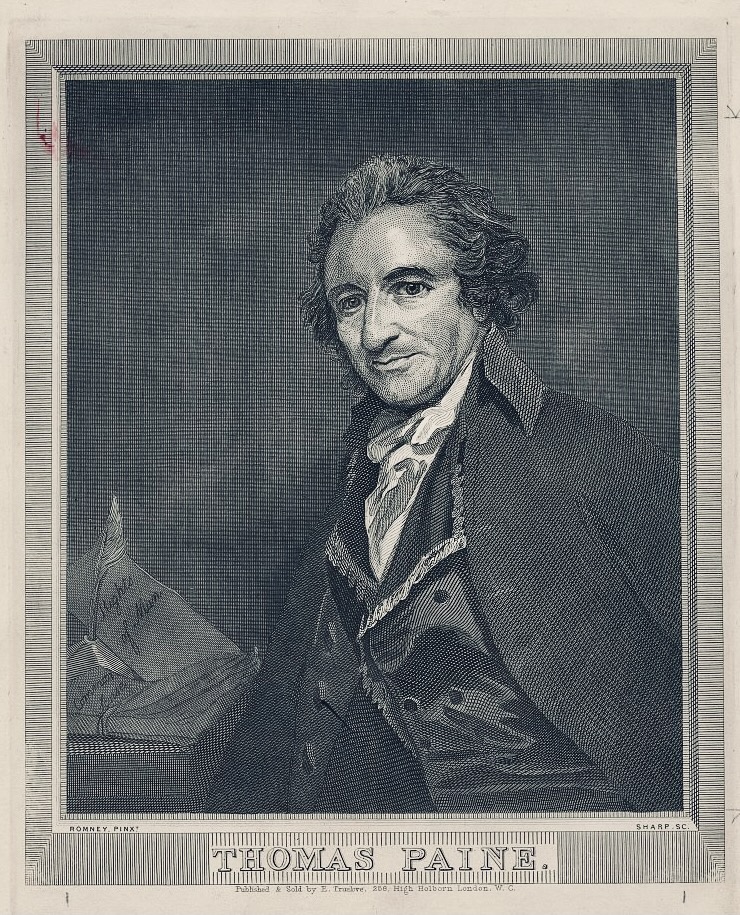

American history teachers are familiar with the broad context behind the publication of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense in early 1776. Paine, an impoverished immigrant from Great Britain, arrived in British North America in November of 1774, armed with little more than a raw talent for political rhetoric and a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin. Franklin’s letter enabled Paine to gain employment in the Philadelphia newspaper business. There he began honing his writing skills and started Common Sense in late 1775. Philadelphia publisher Robert Bell published the 46-page pamphlet on January 10, 1776 and hyped it in Philadelphia newspapers. It was an instant hit.

Common Sense: The Right Pamphlet at the Right Time

No one is sure how many copies of Common Sense were printed in 1776. Estimates range from 70,000 to 500,000, with most estimates falling between 100,000 to 150,000. Regardless of the exact number, Common Sense enjoyed enormous popularity. Those who could not buy the book borrowed copies from friends or neighbors. Illiterate Americans heard it read aloud.

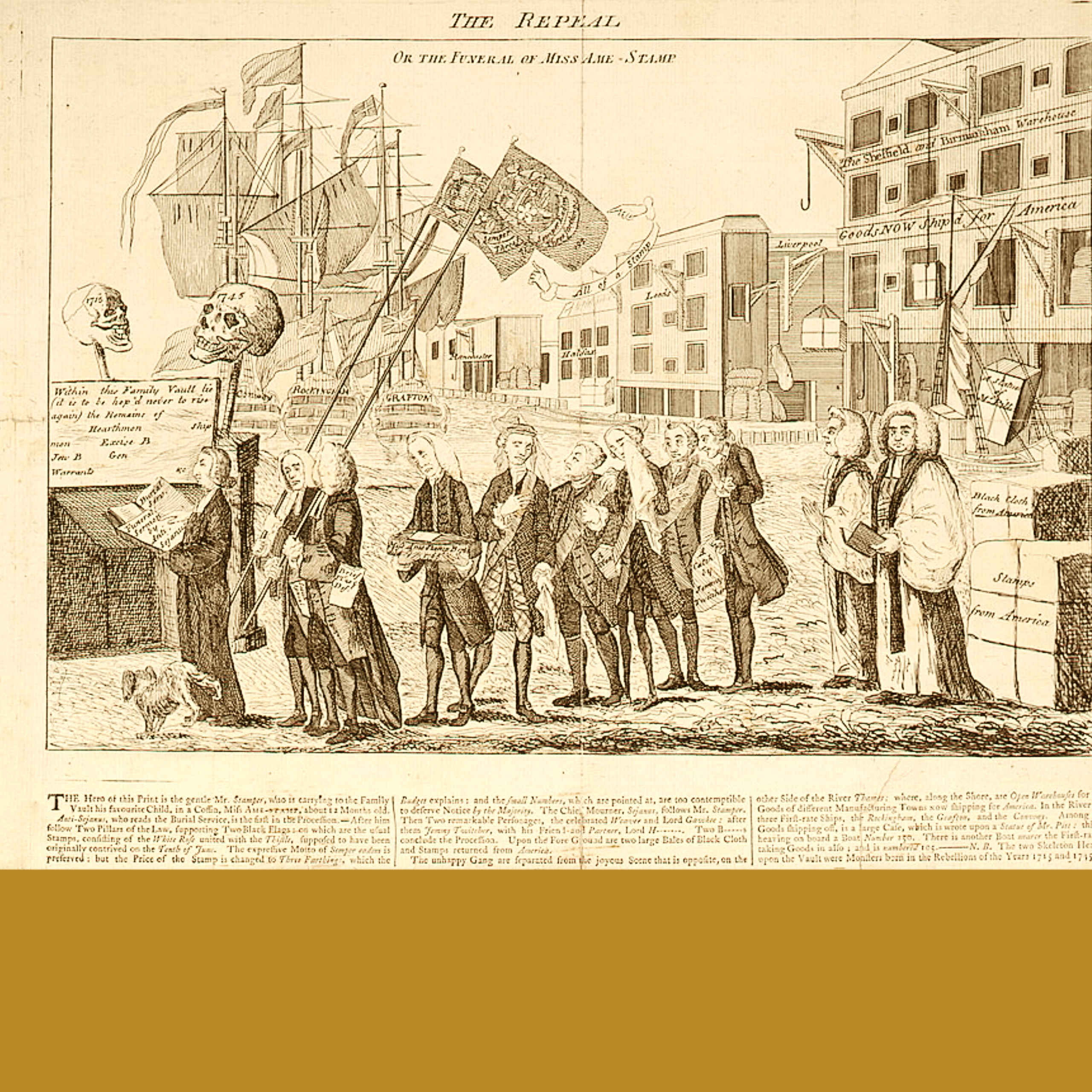

Thomas Paine arrived in North America at an auspicious time. Beginning with the Stamp Act crisis of 1765 and continuing until the battles of Lexington and Concord in April of 1775, the British Parliament tried several times to raise funds for colonial defense and to reduce British debt incurred during the French and Indian War, 1754-1763. Although colonial resistance to Parliament’s actions was fierce, Paine “found the disposition of the people such, that they might have been led by a thread and governed by a reed. Their attachment to Britain was obstinate, and it was, at that time, a kind of treason to speak against it. “Their ideas of grievance operated without resentment, and their single object was reconciliation.” Paine’s clear prose sliced through what historian Joyce Appleby called “the excruciating indecision” gripping the colonists by arguing that reconciliation was unwise and no longer viable.

Paine’s approach gave supporters of independence straightforward rhetorical tools that helped move public opinion toward their cause. “What had until recently been unspeakable and even unthinkable,” historian Robert M. S. McDonald writes, “Paine now put in print.” Parliament was not the problem. The problem was the nature of monarchy—the unjustifiable divine right of kings in general and the British monarchy specifically. Reconciliation was no longer possible because of the inherent nature of monarchy and the specific actions of the British monarch, who had begun using the powerful British military to squash the rebellion. The shift in the colonists’ thinking found its way into the Declaration of Independence’s lengthy list of grievances against King George III when the document was announced less than six months after Common Sense hit the market.

A Controversial Figure

Common Sense was not the first incendiary writing Paine published. In 1772, while working as an excise officer in England, Paine published a tract supporting a petition calling for the reform of the job. Fired from his post, he separated from his wife and auctioned his personal property. After this debacle, he sailed to America, where he applied his animosity toward the British system in favor of American independence. Like his essay supporting Britain’s excise officers, his first political writing in the New World was also controversial. In March of 1775, Paine published “African Slavery in America,” in which he attacked the international slave trade and the enslavement of Africans in the colonies as a violation of Christian principles for which its practitioners must answer to “the final Judge.”

The financial struggles Paine encountered in Great Britain continued in America despite the commercial success of Common Sense. Robert Bell, Paine’s original publisher, claimed—perhaps using doctored books—that the costs to print and promote the tract put him in the red. Bell’s claims forced Paine to seek other publishers, but the vagaries of 18th-century colonial publication kept him from enforcing his rights to authorship. Consequently, Common Sense enjoyed widespread marketplace saturation, with Paine producing subsequent editions with various appendices. Nevertheless, Thomas Paine never made a penny from Common Sense.

Making Revolution Reasonable

One way to analyze Common Sense is to find examples of Paine’s “simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense.” Did he make arguments the average colonist could understand? Did he use simple metaphors and common sense to make his case for independence? In other words, was Common Sense, in fact, common sense? Here are three examples illustrating why Paine’s prose was so accessible to the late 18th-century reader or listener:

One might imagine these examples being quoted, shared, and debated in the taverns and pubs of Philadelphia, Boston, and Charleston in the spring of 1776 as the consensus for independence grew.

Thomas Paine was not the only revolutionary voice pushing for a formal declaration of independence in 1776. Others, such as independence stalwart John Adams, also believed the moment had come, but perhaps Adams was tipping his hat to Paine when he wrote in 1819, “What do we mean by the Revolution? The War? That was no part of the revolution; it was only an effect and consequence of it. The revolution was in the minds of the people.” Through his authorship of Common Sense, Thomas Paine played a vital role in changing the colonists’ minds by shifting their thinking from reconciliation to independence.

Ray Tyler was the 2014 James Madison Fellow for South Carolina and a 2016 graduate of Ashland University’s Masters in American History and Government. Ray is a former Teacher Program Manager for TAH and a frequent contributor to our blog