Daisy Bates and the Little Rock Nine

Two well-known black and white photographs depict the struggle to end racial segregation in Southern schools that continued after the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. Less well known is the woman who organized and supported the brave actions of the Little Rock Nine: Daisy Bates.

The two black and white photographs are iconic images in modern U.S. history. The first photo shows a young black woman walking with school books cradled in her left arm. Sunglasses shield her eyes but can’t hide an expression that is grim, calm, determined. Behind her, a crowd of angry whites presses forward. At the forefront is a woman whose face contorts with hate as she hurls slurs at Elizabeth Eckford, who is trying to enter Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, on September 4, 1957. It was supposed to be the first day of school for her, and for eight other black students, all of whom had been promised admission to the school.

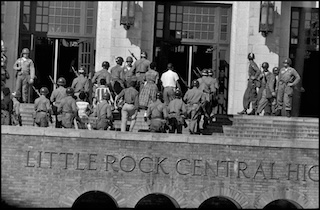

The second photograph was taken three weeks later. The Little Rock Nine, as they came to be known, ascend the main staircase of Central High. They are guarded by helmeted troops from the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division. Many of the soldiers carry rifles fixed with bayonets. The armed escort finally made possible the students’ attendance, literally opening the doors for them.

Together, the photographs tell us much about an important historical moment. More than three years after the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in the Brown v. Board of Education case that racial segregation in education and “separate but equal” were unconstitutional, Elizabeth Eckford and her peers enrolled in the all-white Central High School. Fierce opposition to integration brought not just mobs of whites to the school grounds, but also state troops, who, under orders from Arkansas governor Orville Faubus, blocked the entry of the young African Americans. This flagrant defiance of constitutional order perturbed President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who dispatched troops to Little Rock to ensure compliance with the court’s decision. The images appear to neatly capture the dynamics and drama of the modern Civil Rights Movement. Children determined to receive a good education meet with anger and the menace of violence. Yet efforts to preserve white supremacy and segregation are no match for the law of the land, enforced by federal troops.

But the pictures don’t tell the whole story. Who were these brave young men and women? Who supported and inspired them? What happened to them after they started attending school? To answer these questions, we must look beyond the photographs and focus on a singular figure in the story of the Little Rock Nine, an African American woman named Daisy Bates. Her vision, leadership, and bravery made possible the integration of Central High School in 1957. Not only is Bates important to the history of Central High’s integration, she is also a significant figure in the national Civil Rights Movement. In recognition of her historical contributions, Arkansas selected Bates to be memorialized in a statue recently unveiled at the U.S. Capitol.

Bates was born in November 1914 in a small town in southern Arkansas. White men murdered her mother when she was an infant and adoptive parents raised her. Learning what had happened to her birth mother engendered lifelong anger “about what has happened to my people,” as Bates shared in an interview. Yet on his deathbed her adoptive father counseled, “Hate can destroy you, Daisy. Don’t hate white people just because they’re white. If you hate, make it count for something.”

She made it count. After marrying, she moved with her husband L.C. Bates to Little Rock, where they put their life savings into starting a newspaper, the Arkansas State Press. Coverage of racially biased justice made them frequent targets of spurious arrests. In one instance, the Bateses were charged with contempt of court for an article they published. Daisy Bates also headed the state’s conference of NAACP branches, bringing further harassment. Undeterred, she emerged as a leader in the fight to integrate Little Rock’s schools after the Brown decision. When the white superintendent announced he would only admit one student (whose complexion was so light she could pass as white), Bates helped organize the Little Rock Nine. The students and their parents quickly came to rely on Bates, who had no children of her own, as a protector, spokeswoman, and problem-solver. Governor Faubus’s mobilization of state troops to block the students’ entry was just the first of many crises for her and the Little Rock Nine. The city’s White Citizens Council, formed to oppose integration, distributed handbills portraying her as a criminal because of the prior unjust detentions. The city council ordered her arrest for failing to provide detailed information about the NAACP branch’s membership and finances. She and her husband had to hire armed guards to protect their home. After President Eisenhower sent in the 101st Airborne, Bates had to personally travel to the Little Rock Nine’s homes in the middle of the night to let the families know they could come to school.

Yet entry into Central High was far from the end of the integration struggle. The students faced unrelenting verbal abuse, and, in some cases, physical violence. School officials were eager to use any pretext to discipline the black students, which placed an extraordinary burden on them—even a modicum of self-defense or instinctive retaliation would be grounds for expulsion. Bates knew that if the students could not finish the academic year, not only would their bid to get an equal education be quashed, but also the national campaign to make the Brown decision a reality. As she wrote in her memoir, “Each day after school I sat with the embattled nine in the quiet basement of my home . . . these meetings were not unlike group therapy. In relating the day’s experiences, all the suppressed emotions within these children came tumbling out.” On one especially dangerous day, two of the Little Rock Nine, Minnijean Brown and Melba Pattillo, feared for their lives. Could they seek help from school officials? They didn’t dare try. “Let’s call Mrs. Bates,” Melba remembered saying. “Maybe she can talk to the army or reporters or the President.” Although Bates didn’t have a direct line to the president, the girl’s faith wasn’t misplaced. Every day, Bates was there for the Little Rock Nine. As the harassment intensified, she went to the school and demanded that stronger measures be taken against white offenders. When the school year ended in May 1955, eight of the nine had successfully completed their grade.

In his recent history of the modern Civil Rights Movement, historian Thomas E. Ricks astutely observes that, like an effective military force, the Movement depended on self-discipline, “of putting one foot in front of the other, day after day, of keeping control of one’s own emotions and fears in order to serve a greater good.” Of course, strong leaders nurture self-discipline among their “troops” by modeling restraint as well as courage. For the Little Rock Nine, and the nation, Daisy Bates set that example. As the Chicago Defender reported, “If there had been no Daisy Bates there would have been no 101st Airborne Division patrolling the halls at Central H.S. And no nine negro children in the once all-white high school.”

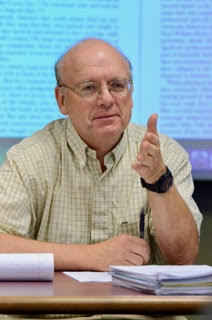

Professor David Krugler (University of Wisconsin, Platteville) is the author of 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back (Cambridge University Press, 2015) as well as of two books on US policy during the Cold War. He edited TAH’s core document collection, The Cold War (2018), and has also written two World War II spy thrillers, The Dead Don’t Bleed (2016) and Rip the Angels from Heaven (2018), both published by Pegasus Crime.

Bibliography

Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock. New York: D. McKay, 1962; reprint, Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Interview with Daisy Bates. Southern Oral History Program Collection, October 11, 1976. Interview G-0009. https://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/G-0009/menu.html

Beals, Melba Pattillo. Warriors Don’t Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock’s Central High. New York: Pocket Books, 1994.

Kluger, Richard. Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1976.

Poston, Ted. “A Woman Who Dared . . . Mrs. Daisy Bates.” Chicago Defender, December 4, 1957.