Federalism and Pandemics: A National Teachable Moment

“Emergencies are crucibles that contain and reveal the daily, slower burning problems of medicine and beyond – our vulnerabilities; our trouble grappling with uncertainty, how we die, how we prioritize and divide what is most precious and vital and limited…”

Sheri Fink, Five Days at Memorial: LIfe and Death in a Storm-Ravaged Hospital

As a non-partisan provider of civic education dedicated to “strengthening the capacities of the American people for constitutional self-government,” the Ashbrook Center and Teaching American History sponsors seminars in which teachers examine the story of America’s past by studying original documents. Federalism is not an especially popular topic for these seminars. It is difficult to understand. It is challenging to teach. Perhaps that is because the dividing line between state and federal powers, never distinct, has been blurred over time.

Yet because matters of public health have historically been assigned to the states under their broad police power, federalism is now being tested––and the stakes are life and death. Covid-19 has engaged the United States in a large-scale social and medical experiment designed to “flatten the curve” by slowing the disease’s spread through the population. The goal is to reduce hospitalizations of Covid-19 victims so that medical staff are not overwhelmed, supplies are not exhausted, nor patients needing ventilators left without them. Hopefully, the experiment will be successful, and we will not see hospitals rationing ICU beds or ventilators.

How should we apply federalism’s principles when pandemics do not recognize state borders? What role, if any, should the federal government play in planning for disasters, responding to disasters when they occur, or assisting states recovering from a disaster’s economic impact?

This is a national teachable moment: when the crisis has passed, we will look back on mistakes made and lessons learned. Will we apply the right lessons with wisdom and prudence?

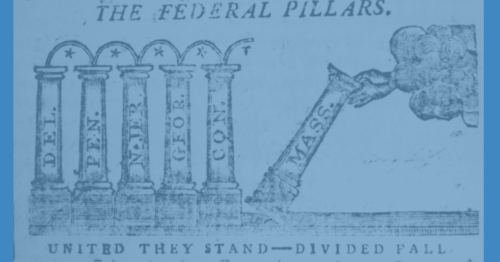

Issues of federalism have plagued our politics since the colonial era. Those drafting our constitution in 1787 understood that Parliament’s inability to envision shared sovereignty “had torn the British Empire apart … and had bedeviled America’s first efforts… to create a limited constitutional government…” with the doomed Articles of Confederation.[1]

Some see federalism as a strength in coping with Covid-19. They see “the best of both worlds: a coherent policy for the entire country that is simultaneously flexible for local contingencies.”[2] Advocates of federalism find outcomes where “some states may initially suffer while others succeed” as an acceptable consequence of a flexible governmental disaster response.[3] New York is not Wyoming; Florida is not Northern Idaho. A one-size-fits all solution won’t work for an event with a national impact, in the view of federalism’s supporters.

Critics of federalism see unequal outcomes as morally unacceptable: “a major weakness in the federalist system of public health governance.” Allowing states control of the crisis response results in uncoordinated efforts. One state’s slow response may unnecessarily cost lives in other states. Critics argue that a national response is more efficient and cost-effective in public health emergencies.

Pandemics present unique challenges to the delicate balance the framers struck between state and national authority. Pandemics impact a much larger geographic area than tornadoes, hurricanes, or forest fires. The risk of illness and death from a novel airborne virus arrives in invisible air currents, slowly picking its victims. No one is immune, yet some are mysteriously spared. After a violent storm, neighbors often share food, drinks, and fellowship. Waiting for a pandemic to pass, neighbors withdraw from fellowship. Charitable organizations cannot mobilize without a means to protect their employees and volunteers from contracting the virus. Pandemics divide us: political divisions deepen.

Behind our current argument over the proper pandemic response lies a longstanding disagreement over federalism. When this crisis passes, students will likely ask their teachers to explain the responses to the pandemic by state, local, and national governments. Though they may not know the term federalism, they will ask: Why was California’s response different from Georgia’s? Why didn’t the president order a nationwide shutdown? Why was it left to the call of individual state governors to shut down and reopen their states’ schools and businesses as they saw fit? What are the advantages and disadvantages of the federalist system?

Here are just a few examples of primary source documents teachers can find on our website, teachingamericanhistory.org, that help teach the constitutional roots of federalism.

- June 8, 1787 debate at the Constitutional Convention on a proposal by Charles Pinckney and James Madison to grant Congress veto power over state legislation. Teachers can help students analyze why Pinckney and Madison proposed what we view today as a radical departure from the principle of federalism.

- June 21, 1787 – debate on federalism as Convention delegates continue to deliberate the division of authority between state and national governments.

- Federalist 45, in which James Madison analyzes the extent to which powers granted to the national legislature “will be dangerous to the portion of authority left in the several States.”

- Brutus I: The antifederalist, Brutus, questions “…, whether the thirteen United States should be reduced to one great republic, governed by one legislature, and under the direction of one executive and judicial; or whether they should continue thirteen confederated republics, under the direction and control of a supreme federal head for certain defined national purposes only?” He concludes that ratifying the Constitution will result in one consolidated government.

- Stephen A Douglas: The Dividing Line Between Federal and Local Authority – Douglas disputes Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party’s contention that Congress had the authority to regulate slavery in the territories.

After this crisis, TAH will continue to partner with local school districts and historical organizations, hosting our One-Day Seminars for social studies teachers. These seminars provide an opportunity for teachers to explore themes, events and concepts, like federalism, in American history and self-government through the study of original historical documents. We hope you will be able to join us at a seminar near you very soon!

[1] Amar, Akhil Reed, America’s Constitution: A Biography, p. 105

[2] See “Pandemic proves the wisdom of federalism” by Jay Cost, The Washington Examiner, April 2, 2020

[3] See “Pandemic Federalism”, John Yoo, National Review, March 20, 2020