How History Illuminates Literature, and Literature Deepens History

Why might teachers seeking a Masters’ degree in history and government take time to read literature? Why might those who teach literature study history? Two teachers in last summer’s “Immigration to America” course explain their motives for taking the course—and what they learned.

Tyler Nice wanted to challenge himself. Having taught Advanced Placement US History for ten years at Thurston High School (just east of Eugene, Oregon) he felt well-grounded in most aspects of our nation’s history—except immigration.

He knew he would learn a lot from the history professor co-teaching the course, Dan Monroe of Millikin University. Nice had appreciated Monroe’s candor and clarity in the core course on Sectionalism and Civil War. “In the first session of that class, Monroe said, ‘The primary cause of the Civil War was slavery.’ I appreciated that he wanted to give us a definitive historical answer” to a question often muddled by historiography.

However, reading literature would take Nice outside his comfort zone. “I’m a huge reader of nonfiction, but I really don’t enjoy reading fiction that much. Still, I felt it would be a good challenge to try to do it.

“I’m so glad I did! It was a wonderful course,” he said. Reading the text of legislation helped Nice grasp the changes in immigration policy during the 19th and 20th centuries. Reading first-person narratives from immigrants themselves helped him understand “the impact of these laws on people’s lives.” Reading fiction and poetry written by and about immigrants deepened this understanding.

“Other classes in the MAHG program give us short first-person narratives, but this class gave us entire short stories and even novels. In my current course (The Rise of Modern America, 1914-1945), we read a first-person account of a German American being harassed during World War I. That was illuminating—but it’s just two pages.” In the history/literature course, teachers read long portions of Willa Cather’s My Antonia, experiencing the homesickness of a Bohemian American musician transplanted from an old European city to a farm on the plains of Nebraska. They explored the cultural misunderstandings complicating friendship between the Bohemian man’s family and his native-born neighbors. “The medium of fiction gives authors the freedom to express complex ideas through symbols and other creative language,” Nice noted.

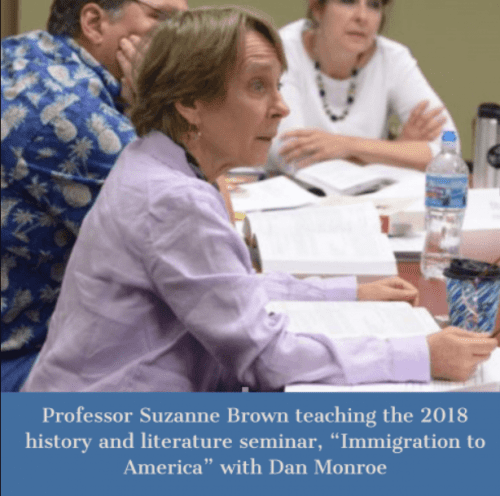

He traced such symbols through a memoir he found “kind of bizarre”: Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior. Kingston creatively reproduces her childhood psyche, caught between American culture and her mother’s vivid memories of the home country. The heroic story of her mother as a medical student in China gives way to the family’s current reality as owners of a San Francisco dry-cleaning business. Kingston renders her mother’s versions of family history and folklore in strange, even “grotesque” images. This “left me with a lot of questions,” which Nice worked through in class discussions with Professor Suzanne Brown. He enjoyed not only Brown’s “ability to pull nuance out of literary texts” but also her enthusiasm. When class participants noticed an image pattern resonating with symbolism, Brown “was so excited!”—which fed the teachers’ excitement. Nice remembers the page of the novel “where we realized what the main character’s mother means when she refers to ‘ghosts.’ They are non-Chinese Americans,” people whom the mother regards as insubstantial in their customs, yet menacing in their watchfulness. Speaking of the traditional Chinese food she prepares—delicacies to her, unappetizing oddities to white Americans—the mother boasts she “can defeat the ghosts: she can out-eat them,” Nice said.

The course gave Nice “a more comprehensive understanding” of the struggle of immigrants to assimilate into American culture.

Karen Cranston-Barney took the course to gather ideas for a social justice course she hopes to teach. She covers Freshman Studies at Veterans Tribute Career and Technical Academy (VTCTA), a public magnet school in Las Vegas. Cranston-Barney’s husband, a MAHG graduate who also teaches at VTCTA, suggested she take the course.

Like Nice, Cranston-Barney wanted to fill a gap in her historical knowledge. Although a social-studies major as an undergraduate, she minored in English and has primarily taught language arts during her twenty-six years in education.

“I have a solid background in African American studies and women’s studies,” Cranston-Barney said. “My knowledge gap was in immigration. We have such a large immigrant population at our school, I felt like I really needed to get some of that knowledge under my belt.”

At first, she mostly listened during seminar discussions. “It had been so long since I read history,” she said; “and I was so impressed by the caliber of the other students. You could tell which teachers were finishing up their studies in the program; you could see all the knowledge they were able to apply to the readings for this class.”

Teachers new to the animated atmosphere of MAHG’s small, conversation-sized classes may need a nudge to jump in. Professor Brown provided the push after receiving an email from Cranston-Barney about the short story, “Between Mass and Vespers.” In it, an Irish Catholic priest tries to set a wayward immigrant youth on the right path. Cranston-Barney asked Brown if “the title of the story referred to the priest’s search for absolution between morning (mass) and evening (vespers).” As a child, playing on the beach, the priest had been unable to rescue his younger brother when he had been swept out to sea by a freak wave. Did his guilt push him to rescue the young immigrant? Brown asked Cranston-Barney to raise the question at the next class session.

Teachers new to the animated atmosphere of MAHG’s small, conversation-sized classes may need a nudge to jump in. Professor Brown provided the push after receiving an email from Cranston-Barney about the short story, “Between Mass and Vespers.” In it, an Irish Catholic priest tries to set a wayward immigrant youth on the right path. Cranston-Barney asked Brown if “the title of the story referred to the priest’s search for absolution between morning (mass) and evening (vespers).” As a child, playing on the beach, the priest had been unable to rescue his younger brother when he had been swept out to sea by a freak wave. Did his guilt push him to rescue the young immigrant? Brown asked Cranston-Barney to raise the question at the next class session.

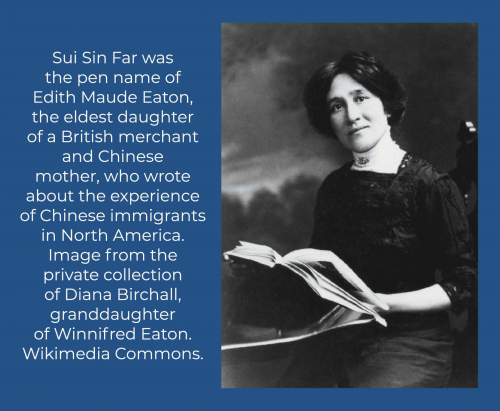

One story assigned for the course, Sui Sin Far’s “In the Land of the Free,” strongly impressed both teachers. Cranston-Barney explained the plot: “A Chinese couple are living in San Francisco in late 19th century America; the wife goes back to China to give birth to their son, but when she returns with the baby, American officials will not let them off the boat, because she doesn’t have immigration papers for the son. Eventually the son is taken from them. Ten months go by, as they consult an attorney who is taking advantage of them to get money, until finally the mother can retrieve her son from the convent where he has been kept. The boy doesn’t know her and is afraid of her.”

Nice noted that the story was set in the time period following the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. “When you read the textbook account of this law, it’s just a vocabulary term you tell students to memorize.” But when you read the short story, “you see the law’s impact on immigrant lives.”

To Cranston-Barney, this story was “an amazing discovery. I could use it in my classroom to get students to look at immigration laws historically, then to get them to think about what is happening now from a social justice perspective. We tend to read about injustices in the past and think, ‘that is so wrong; you should never take a child from the mother.’ Yet you cannot look on this case from a superior present-day perspective.”

To Cranston-Barney, this story was “an amazing discovery. I could use it in my classroom to get students to look at immigration laws historically, then to get them to think about what is happening now from a social justice perspective. We tend to read about injustices in the past and think, ‘that is so wrong; you should never take a child from the mother.’ Yet you cannot look on this case from a superior present-day perspective.”

The course Cranston-Barney plans focuses on peace and conflict in American society. “We’ll start with historical issues and work our way up to more contemporary ones.” Through reasoned conversations about history, the freshmen can begin “exploring their core beliefs” and the political decisions consistent with those beliefs before taking on more highly charged current issues.

Studying history before current events seems wise for students everywhere. Compared to discussions of the past, discussions of the present often emphasize the concrete effects of policy, visible around us and arousing passions before thought. Historical fiction provides a space in which students can consider the connection between principle and practice more objectively.

At the magnet school where Cranston-Barney teaches, it’s important to progress thoughtfully from history to current events. Students who attend VTCTA take elective courses related to public safety and law enforcement. Some graduates go directly into EMT or 911 dispatch work. “We’d like to help our students start dealing with sensitive social issues before we send them into practice,” she said.

Nice sees less opportunity to use literature in the fast-paced AP US History class. Yet he hopes to soon begin teaching courses that will afford more time for both primary documents and literature. The MAHG degree, which Nice will complete next summer, will qualify him to teach in Oregon’s dual enrollment program. While APUSH and AP Government race students through everything that might appear on the high-stakes final exam, dual enrollment courses allow time to foster critical thought through text analysis. “My ultimate goal is to recreate the MAHG experience in my own class. I want kids to read primary sources and then come together to discuss them in a deep, rich, and meaningful way.”