The Case that Defined the School Desegregation Remedy

When people think of desegregation remedies, busing is likely the first thing to come to mind. Why? Because of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg, which was decided fifty years ago today.

The significance of Swann is difficult to overstate. Because busing became almost synonymous with desegregation, the case in some ways overshadows Brown v. Board of Education, which famously did not define desegregation. In fact, throughout the entire history of desegregation the Supreme Court never precisely defined what the word meant. Hence, it’s not surprising that it came to be defined by a particular remedy such as busing.

Swann is also the most successful example of judicially mandated metropolitan desegregation. However, by giving birth to busing it also eroded political support for desegregation, which contributed to the federal court’s withdrawal from the issue. The decision also thrust district court judges into managing the minutia of school district policy, a task which many judges proved to have neither the inclination nor the aptitude to do well.

Understanding the successes and failures of Swann requires recalling a case decided three years earlier, Green v. New Kent County School Board (1968). In Green, the Supreme Court set in motion the principles that led to Swann. Primarily, the Court held that unlawfully segregated school districts had an “affirmative duty” to desegregate. That meant that they could not just adopt freedom-of-choice plans that left schools overwhelmingly one race regardless of the racial composition of the district. Instead, school districts had to adopt plans that demonstrably reduced racial isolation. For most southern school districts, adopting neighborhood attendance zones was sufficient. But not in Charlotte.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg School District was enormous. Partly urban and partly rural, covering 550 square-miles, the district served 84,000 students, 29 percent of whom were black. However, most of those black students were concentrated in one quadrant of the district. Prior to Green the district had, under court order, adopted a desegregation plan focusing on geographic attendance zones and voluntary student transfers. However, over half the black students still remained in schools without any white students or teachers. Following Green, Federal District Court Judge James McMillan ordered a massive busing plan to eliminate those overwhelmingly one-race schools and have them match the 71:29 ratio of white to black students in the district.

One obstacle stood in the way of this plan, The Civil Rights Act of 1964. The act, which was really responsible for starting the process of desegregation after ten years of “massive resistance” to Brown, seemed to forbid both busing and the use of numerical disparities as a basis for judicial intervention. “Nothing herein,” Title IV of the act says, “shall empower any official or court of the United States to issue any order seeking to achieve a racial balance in any school by requiring the transportation of pupils or students from one school to another or one school district to another in order to achieve such racial balance.”

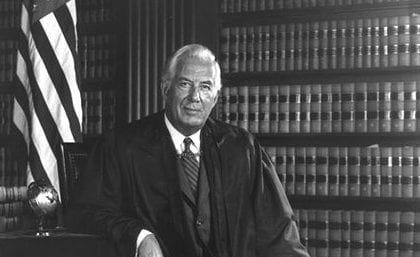

In 1971, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the district court’s order sweeping aside the limits imposed by the Civil Rights Act, citing the judicial equity power, which the Court said gave courts broad latitude in fashioning remedial decrees . However, the unanimity masked deep disagreement on the Court. We now know that the decision, written by Chief Justice Burger, was the subject of intense negotiation among the justices and would prove to be the last time the Court ruled unanimously on a desegregation case. The disagreements among the justices were reflected in Burger’s opaque language. For instance, on the use of ratios, his opinion sanctioned their “limited use” but failed to define limited. Despite this vagueness, lower courts interpreted the decision to mean that any departure from the overall racial composition of a school district in individual schools constituted evidence of unlawful segregation. The fissures papered over by Swann would start to reveal themselves two years later in Keyes v. Denver School District no. 1 and then be on full display in 1974’s Milliken v. Bradley.

What happened in Swann’s wake ends up being most important. In Charlotte itself the results were largely positive. Unlike many “deep South” states, Charlotte’s immediate response to Brown was more moderate. And later, when civil rights activists pressed for more than symbolic and token desegregation, it found the white business community in the city largely supportive. Those leaders had ambitions to make Charlotte a major financial hub. Racial animosity, they realized, wasn’t good for business. Also, the fact that Charlotte consolidated its school district with the surrounding Mecklenburg County in 1960 limited the potential of “white flight”.

Those conditions, however, did not exist in most other cities and school districts that were forced to implement busing after Swann. Immediately following Swann, large majorities—75-90 percent—of white parents consistently expressed opposition to forced busing. Black parents also came to oppose busing. For a few years in the mid-70s and early 80s, support for busing crept above 50 percent for black parents, but by the mid-80s stable majorities of 55-60 percent opposed it. This opposition not only led to substantial white flight from school districts under busing plans but also prompted some middle-class “black flight” as well. White flight, of course, reduced the effectiveness of busing, and the overall departure of middle-class families left many districts with a reduced tax base and fewer parents with the background and resources to help maintain support for the school system.

Busing also had broader political implications. In Detroit, a district court judge consolidated all the metropolitan districts into a single district with large-scale busing. George Wallace rode a wave of animosity to that plan to an overwhelming victory in the 1972 Michigan Democratic Presidential Primary. That political backdrop was clearly looming over the Supreme Court’s 1974 decision in Milliken v. Bradley, which ruled that suburban school districts could not be compelled to participate in a desegregation remedy if they did not contribute to the constitutional violation. Instead, judges presiding over school desegregation cases had to rely on compensatory educational programs and magnet schools to create some integration in their districts. Thus, almost as soon as the court sanctioned busing, it began limiting its use. Swann then stands both as one of the 20th century’s most aggressive exercises of judicial power and as an exercise of power which eroded the political and social foundations of its ambitions.