Indigenous Columbus Day

Did you celebrate Columbus Day or Indigenous Peoples’ Day? The two holidays have a lot in common.

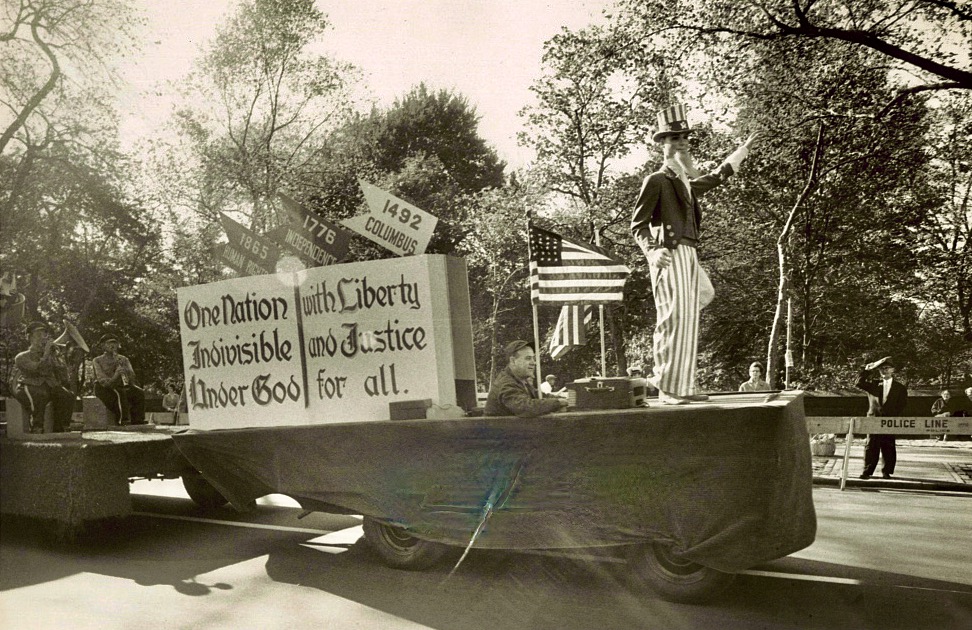

Columbus Day was first proclaimed by president Benjamin Harrison on July 1, 1892. (The Federal holiday came later.) Harrison acted in response to the outrage caused by the lynching of 11 Italian Americans in New Orleans, who were acquitted at trial for murder but suffered nonetheless from popular “justice.” The pressure Harrison responded to came mainly from Italian Americans and the government of Italy, a sign of the resistance to accepting Italian immigrants into American life. But Italians were arriving in growing numbers. As the Library of Congress reports, in the 1880s, Italian immigrants “numbered 300,000; in the 1890s, 600,000; in the decade after that, more than two million. By 1920, when immigration began to taper off, more than 4 million Italians had come to the United States, and represented more than 10 percent of the nation’s foreign-born population.” Lobbying and political organizing by these immigrants and their children, and by such organizations as the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic men’s society, led eventually to the establishment of Columbus Day as a national holiday.

Like Columbus Day, Indigenous People’s Day resulted from lobbying and politicking. This began in the 1960s and 1970s, inspired by the African American civil rights movement. Like Columbus Day, promotion of Indigenous People’s Day succeeded first at the local level, in South Dakota and Berkeley, California, and slowly gained broader acceptance. It is now an official holiday in a number of states. Even Columbus, Ohio has replaced Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day. For 2021, President Biden proclaimed that October 11 would be both a Columbus Day and an Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

Labor Day has a history like both Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Local and informal days to celebrate labor, to elevate its status, and legitimize its efforts to organize became more common as America industrialized. But efforts to organize labor also led to conflict and violence. Strikers fought replacement workers and the security forces hired by employers, while police and even troops fought strikers. Some historians claim that America’s labor struggles were the most violent of any industrializing nation. In 1894, after one of these violent episodes, a railroad strike, in which president Grover Cleveland authorized the use of troops, in large part to keep the mail moving, Cleveland signed a bill making the first Monday in September Labor Day. He signed the bill to restore his standing with the labor movement’s voters after having helped break the railroad strike, but also as a larger effort to conciliate labor. Establishing Labor Day was a step toward integrating organized labor into American life and politics.

The most important point about these holidays—as well as Martin Luther King Day and Juneteenth, and such celebratory months as Black history, Women’s history and Hispanic Heritage months—is that they all are a political response to a grievance, an effort to do justice to those thought neglected or harmed in the past. The political mobilization at the local and eventually national level to establish these holidays and celebratory months was an important part of the way in which various groups created a place for themselves in American life.

But isn’t there a difference in the case of Indigenous Peoples’ Day? Isn’t it meant to replace Columbus Day, as it has in Columbus, Ohio? None of the other holidays or celebratory months did this. They gave official recognition to various groups and thus brought them into our national life without excluding others. Indigenous Peoples’ Day excludes and therefore denigrates what Columbus stood for. It does so justly, many now would add.

This exclusionary effort is the intent of many, perhaps most, of those who promote the new holiday, often with an air of moral superiority. If so, they are wrong in both their intent and the manner in which they seek to achieve it. Columbus was certainly strong-willed and sometimes brutal in his methods. But he was brutal toward Spanish colonists as well as the native inhabitants, and never more brutal, he insisted, than circumstances compelled him to be. European settlement did wreak havoc on indigenous populations. Yet Native American tribes did not coexist peacefully before Europeans arrived. Indigenous people murdered each other, stole each other’s land, held slaves, and occasionally ate each other. In their often fierce competition, some native groups disappeared—in a genocide, we might say. In their common acquisitiveness and brutality, the Europeans and the natives showed in one way the truth of the statement that all men are created equal. Given this equality, it is hard to see why one celebratory day should replace another.

Also, we should note the unnoticed hypocrisy of those who mobilize against Columbus Day. If Columbus is to be blamed for bringing to the western hemisphere the diseases that destroyed so many indigenous people, for example, then he should be praised for also bringing the ideas of human equality, natural rights and respect for the most disadvantaged that indigenous people and so many others now use to succeed politically. Indigenous people are today the beneficiaries of Columbus, of European expansion, as we all are.

In truth, all of the celebratory days and months say more about the concerns of the time in which they were lobbied for and finally accepted than they do about anything that happened in the past. So, let us celebrate both Indigenous Peoples’ Day, especially if that helps some Americans feel more a part of our national life, and Columbus Day, and let us use the day to learn more about our common and complex history.