Larry Dorenkamp Opens a New Door

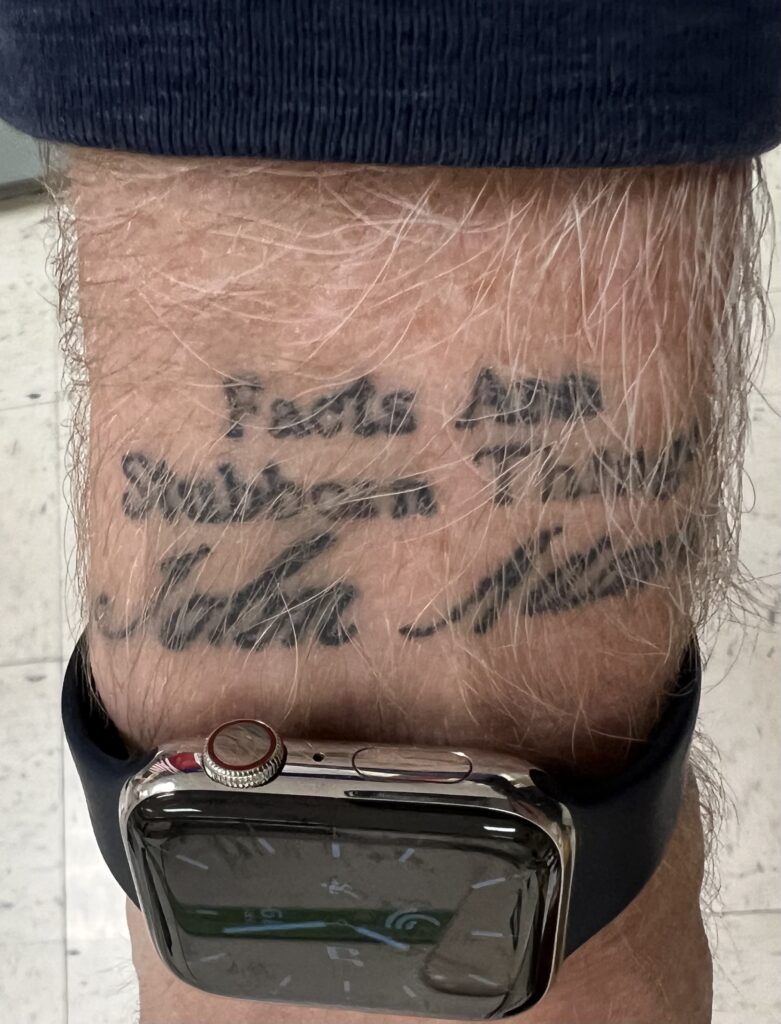

Larry Dorenkamp uses aphorisms to communicate life lessons to students in his 8th grade American history course at North Hills Middle School, near Pittsburgh. “Words matter,” he says, emphasizing the need to “say what you mean, and mean what you say.” When teaching students to consider the available evidence before forming opinions about history or current events, he says, “Facts are stubborn things.” This spring he added another aphorism: “Don’t close any doors.” Dorenkamp wanted to encourage students to reach beyond their own limited expectations for what they can achieve. He did so while announcing an exciting new chapter in his own life. He leaves for Norway on July 31st to begin a yearlong Fulbright Teaching Fellowship.

Overcoming Fears About Transcultural Communication

“When you step outside of your comfort zone, you open doors that you didn’t know were there,” Dorenkamp told his students. For twenty-seven years he has honed his teaching skills; he spent four years teaching at a middle school in Herndon, Virginia, and over two decades at North Hills. “My biggest fear has always been that I would become a teacher who just comes into the classroom to get a paycheck before going home. That fear drives me to make myself better,” he said. It led him to seek a Madison Fellowship and earn a Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) at Ashland University. It also led him “to start the Fulbright application,” he said, “but then I stopped.

“A colleague in California encouraged me to keep going—he said, ‘Quit being a blankety-blank, just do it.’ I was afraid of failure. But I did it, and here’s the door ready to open.” Addressing his students frankly, Dorenkamp said, “I don’t know whether you think I’m a good or bad teacher, but I work hard. I think I’ve got this under control. But now, I’m afraid I’ll get to Norway, and the students there won’t be you. Will my humor work with them? My sarcastic quips? All these tools I work with—my energy—perhaps it will be too much!”

Planning Lessons to Illuminate American Life

Dorenkamp’s appreciative students didn’t think he’d have trouble. Some were already helping him channel his fears in a productive direction, by helping him with the lesson plans he will use as he roves among middle schools in Norway. The Fulbright program has asked him to prepare five separate lessons on American history and culture that he can present in multiple schools. Dorenkamp is preparing six or seven lessons. Descriptions of these will be sent to middle-school teachers in Norway. Any teacher may look over the list and request that he visit their class to present one of the lessons—or perhaps a lesson on an entirely different topic.

Some of Dorenkamp’s lessons deal with the US Constitution; some with aspects of American history; some with American youth culture; and some with the connection between civic and personal life. All the lessons incorporate audio or visual resources. Many invite Norwegian students to compare their own experiences to those of American youth. Dorenkamp asked his students at North Hills to help him prepare some of the resources he will use.

Bringing the American Student’s Perspective to Norwegian Students

A lesson called “Here and There” will prompt Norwegian students to contrast the rights they are guaranteed with those guaranteed to American students. It will show how the First, Fourth and Eighth Amendments to the Constitution have historically been applied to students in American public schools. Because schools claim an “in loco parentis” status when setting rules for student behavior, they have often restricted students’ rights regarding free speech or search and seizure, for example, and Supreme Court cases have resulted.

To make video resources for this lesson, Dorenkamp asked ten of his students to read a summary of one of ten Supreme Court decisions bearing on students’ rights. Once he was sure the student understood the case he or she had been assigned, he videotaped them (after getting their parents’ permission) acting in the role of the plaintiff in the case, explaining how they felt their rights were being violated. “After the Norwegian students watch each video, I’ll ask them, ‘If this happened here in Norway, what would be the consequence for the student?’ After we discuss this, I’ll show them how the Supreme Court ruled in the American student’s case.” He’s also prepared lessons on the “History of Slavery and Racism in America”; “Immigration in America: Building a Nation”; and “We’re the Kids in America.” The latter is “a look at what it means to be a teenager in the USA.” Dorenkamp has circulated a survey among eighth graders at North Hills, capturing their anonymous responses to questions about their lives. “For example, it asks, ‘Do you wish you were already an adult? If so, why?’ and ‘What are the hardest things about school?’” Dorenkamp explained. He’ll use the survey results to answer the Norwegian students’ questions about their American counterparts.

Popular Culture Communicates Transnationally

Another lesson, on “The History of Modern American Through Social Protest Music,” uses about 40 popular songs, many of them known as well to Europeans as to Americans, from the post-World War II period to today. Dorenkamp plans to play each song for the Norwegian students in a music-video version, then without the video. Very often the music video projects moods or ideas that run counter to the song’s lyrics.

He cites a well-known video played to the backdrop of Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA.” The video mixes footage of Springsteen’s impassioned singing with images of “Americana—picnics, baseball, high school prom night, carnival rides. Before I ask the students to analyze the lyrics, I’ll play the song again to a blank screen.” The lesson should give Norwegian students practice in their aural comprehension skills. Norwegians begin studying English alongside Norwegian in their first year of public school—yet even American listeners often focus more on visual input than on the actual words being sung.

A final lesson—actually, the one that Dorenkamp sees as one of the first lessons a social studies class should tackle—uses the Foo Fighters’ song “There Goes My Hero” to prompt students to think about their own strengths. The lesson prompts students to think about “stepping out of their own comfort zones” to become contributors in their own communities. Dorenkamp has prepared 15 slides, each featuring a popular superhero, and listing ten of the superhero’s qualities—not “super powers” so much as moral commitments, social skills, or other strengths that the “ordinary” person can cultivate. To positively engage in civic life, each of us must cultivate good intentions, habits, and skills. “I’ll ask each student to pick five or six of the qualities they find in the slides that reflect their own strengths, and then to create a super hero shield representing those.”

Fulbright program administrators have encouraged Dorenkamp to do this careful planning. But they’ve also advised him he may need to ditch his plans and respond to other requests. “I have a lesson on the Electoral College I could teach without any notes. I’d love to do that,” Dorenkamp said. “But I’ve been told that during the first 20 minutes in each new classroom, all the students will want to do is to ask me questions.” He expects to spend only a day or two in each school he visits. He’ll also meet with Norwegian teachers, sharing pedagogical practices he’s used in his Pennsylvania classroom. “I’m fine with that. I’ve traveled with my colleague Joe Welch to make presentations at National Council of Social Studies meetings all over the country.” Welch, who also teaches at North Hills, was a finalist for National Teacher of the Year in 2022. “We plan many of our lessons together,” Dorenkamp says. “It’s great to have such a colleague.” Like Dorenkamp, Welch has participated in TAH multiday programs; he too appreciates the content knowledge these programs offer.

How MAHG Extended Dorenkamp’s Effectiveness

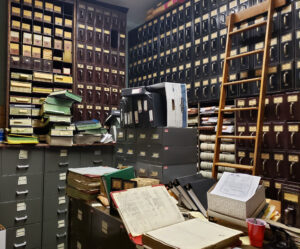

Dorenkamp “opened the door” on getting a Master’s degree after attending a weekend colloquium offered by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello. This first immersion in content-rich professional development left him wanting more. Looking around for programs, he concluded that MAHG offered the only program likely to meet his needs as a working teacher. Offered a first course tuition free through the Allegheny Foundation, he took Professor Chris Burkett’s seminar on the American Founding in the summer residential program. This convinced him. Meanwhile, he built an application that was accepted by the James Madison Memorial Foundation Fellowship, which funded his graduate study.

“I can’t say enough great things about MAHG. I’m a better in-class than online learner, and MAHG offers residential seminars during the summer,” Dorenkamp said. “I also appreciated that the exams used essay questions, and were designed to give you time to process what you’d learned, to really think about what you wanted to write.”

The program also helped Dorenkamp think through his own reasons for teaching through primary sources. “When you teach through primary sources, you don’t teach kids what to think; you teach them how to think and form their own opinions.” You also help them to feel empathy for the people of the past, he said; and when you cultivate this empathy, you build their capacity to feel empathy for fellow students and fellow citizens.

“There’s not enough empathy in the world today. Whether or not I support Black Lives Matter isn’t the issue. What matters is whether I can get inside a BLM activist’s head and understand why he feels so marginalized,” Dorenkamp explained. Empathy builds community across differences.

For his culminating project in the MAHG program, Dorenkamp prepared a capstone using primary sources to illuminate key moments in American history from the colonial through the Civil War period. He hoped to encourage a sense of connection between his students and the history they were studying by focusing, when he could, on the history of his own region. For example, he developed a lesson on the French and Indian War that uses George Washington’s journal of his experience as a major in the militia of Virginia, leading an expedition to construct a fort in an area that once was the frontier, but now is Pittsburgh.

“I present this unit to the kids as the story of a young person only a few years older than they are today, who hoped to make a name for himself. He left his comfort zone” in colonial Virginia to travel into the wilderness, encountering native tribes who were allied with the French and hostile to him; journeying through challenging terrain; and crossing swift-flowing rivers choked with winter’s ice. “I ask students, what will you aspire to do? Where are you going to put yourself in the world?” They don’t have to take leading roles on the national stage, or attempt risky expeditions similar to Washington’s, he tells them, in order to make a meaningful difference in their own communities. “The people who volunteer in their own churches or civic groups do important work.”

Dorenkamp hopes to share this life lesson—along with his humor and energy—with the students he’ll meet in Norway. “I’ve made these lesson plans, and they may bomb!” he laughs. “In which case I’ll just have to try something else. I know I will learn a lot.”