Lincoln: Bridging the Founding and Our Own Time

A conversation with Joseph Fornieri and David Tucker

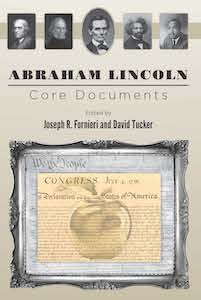

Teaching American History has released a new document collection, Abraham Lincoln: Core Documents. A compilation of Lincoln’s most important speeches, letters, and private notes, the volume was edited by Joseph Fornieri, Professor of Political Science at the Rochester Institute of Technology, and David Tucker, Senior Fellow at the Ashbrook Center and General Editor of the TAH Core Document Collection. Both Fornieri and Tucker are faculty in TAH programs. Fornieri has written numerous articles and four books on Lincoln, including Abraham Lincoln: Philosopher Statesman (Southern Illinois University, 2014). He also edited Free Speech: Core Court Cases (2020), a volume in TAH’s core document series. Tucker’s books include Enlightened Republicanism: A Study of Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia (Lexington Books, 2008); Resistance and Revolution: Moral Revolution, Military Might, and the End of Empire (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016); and three volumes in the core document series, most recently Slavery and Its Consequences (2020). Below, the editors talk with TAH Communications Editor Ellen Tucker about Lincoln’s pivotal importance to American history and political thought.

ET: This is the first core document volume TAH has published that features a single author. Why produce a collection of Lincoln’s writing?

DT: We’ve always considered Lincoln’s words the foundation of Teaching American History. Everybody involved in setting up our programs looked to Lincoln as the statesman, the person who best understood the United States and its principles, and was most effective in defending and supporting them. For Lincoln, liberty and equality went together. Explaining and defending this understanding of equality, as expressed in the Declaration, preoccupied him throughout his career.

Second, everything Lincoln said about his own time applies to our time. The political situation he faced is very similar to that we face today. On both the left and the right, people deny human equality. We also hear moral condemnation of those on the other side. Lincoln warned about this; he opposed the tendency to moralize politics and to condemn your opponents in a way that implies that they can’t be fellow citizens. Throughout his career, Lincoln tried to combat bad ideas without condemning his opponents’ character. When you take the moral high ground, you imply that your opponents are inferior, that they are less than you, and unequal.

ET: Joe, do you see this as David does? Do you see the idea of equality as being disputed in current discussions of national politics?

JF: I do. As Lincoln said in 1864, “the world has never had a good definition of liberty, and we are sorely in need of one today.” Lincoln talks about two contrasting definitions. For the antebellum South, freedom means the right to hold human beings as property. They interpreted the liberty clause of the Fifth Amendment as guaranteeing them that right. Of course, for Lincoln and the Republicans, freedom is, at the very least, the right to enjoy the fruits of your labor.

Interestingly enough, although as a country we’ve overcome some misunderstandings of equality and liberty, there’s still a debate over the meaning of these terms. For example, in the name of equality, the identity politics of today divides people by race or class or gender in a way that strikes at our common humanity. Whether you’re on the right or on the left, when you speak of racial or ethnic superiority on the one side, or a privileged victimhood on the other side, that strikes at the common bonds of citizenship, denying the fundamental equality between these groups.

Earlier you asked David, “Why Lincoln?” TAH is committed to civic literacy. Lincoln provides great answers to some of the enduring questions about what it means to be American. He also bridges principle and practice. As David said, the power of his writing, in articulating, defending and extending our core principles, is magnified by his actions to save and preserve the American experiment. He’s also a friendly critic of that experiment, as we see in his criticisms of the Mexican War. All these things warrant a special volume dedicated to Lincoln.

ET: Teachers often tell me that Lincoln’s writing is easier for students to understand than say, Madison’s or Hamilton’s—and that for this reason they rely on him to teach American history and principles, even to explain the thinking of the founders. What makes Lincoln’s writing so accessible to readers today?

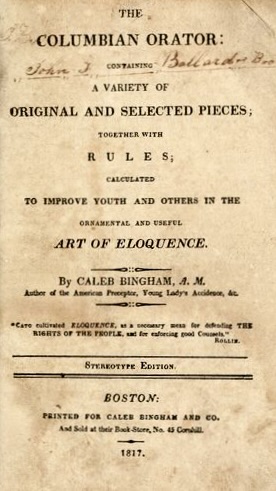

JF: There’s an irony here, in that Lincoln had no formal education. He was spared the excesses of Victorian prose, with its 3000 semicolons. He had a logical mind which he honed as a lawyer. Even as a boy, he later said, when he listened to adults talking, he had a compulsion to restate their ideas in his own mind, to explain them in the simplest manner for himself and for others. This made him an amazing teacher. Of course, his rhetoric was not only clear; it was often poetic. Look at the Gettysburg Address! This comes from his self-education through reading The Columbian Orator and Shakespeare. He had a great ear for the rhythms of speech.

ET: He was also a great joke teller. You can’t tell jokes well unless you’ve got timing down. But tell me, what is The Columbian Orator?

JF: It’s a collection of great speeches and essays, meant to train Americans coming of age during the founding period in the art of persuasion and oratory. It was first published around 1793 and went through about 16 editions. You have writers from Plato to Cicero to Edmund Burke. Both Frederick Douglass and Lincoln turned to it as part of their remarkable self-education. Douglass mentions it several times in his three biographies; it’s the one book that he carried with him out of captivity. Edited by the anti-slavery minister Caleb Bingham, it shows that at the time of the founding, there were decidedly anti-slavery voices exercising an important pedagogical influence on subsequent leaders.

DT: To your question about Lincoln’s accessible style, I’d add that he clearly knew the Bible very well. The Bible was a common stock of images and language for Americans of the nineteenth century, although it is less so today. Also, Lincoln perfected a common-sense approach to arguing cases before juries. He grew up among common Americans, and the stories told about him show that he had a real grasp of how ordinary Americans thought and responded. Those basic responses of people have not changed much in 150 years.

ET: I was talking recently with a teacher in a very diverse school, about 40% African American, and 10% Latino and Asian. This year, when his students read the Fragment on the Constitution and Union, one of them said of the apple of gold, “That’s got to be Biblical.” So Biblical literacy has not entirely disappeared.

Teachers speak of teaching Lincoln’s writing more often than that of any other author, as if Lincoln is central to their teaching of American history and government. Some view Lincoln as providing a bridge between the founding and our post-Civil War understanding of ourselves, even though our politics and institutions changed so much following the Civil War.

JF: Lincoln wrestles with the contradiction in our founding: we are a nation that declares all men are created equal and yet we allow slavery. We’re still dealing with the legacy of that. Lincoln also deals with other causes of tension, such as federalism—the division of power between the state and national governments. He addresses the relationship between law and morality and between principle and practice, as Dave mentioned. He also speaks of the perennial temptation to political utopianism, a pitfall for anyone who invokes principles in politics.

I do think he provides a bridge. Lincoln sees the founding pointing in the direction of freedom for all. The compromises made with slaveholders didn’t nullify the principles. I see Lincoln affirming, defending and extending those founding principles with a logical consistency. A lot of my historian friends use the term “second revolution” when they talk about Reconstruction or the Civil War era. That’s fair; the war brought sweeping changes, destroying an institution that was interwoven in southern society for hundreds of years. But we should not overlook the continuity between our founding principles and political life today.

DT: We can also relate to Lincoln’s view of the founders. The founding generation all spoke of progress; even George Washington uses the word. Lincoln hoped for progress, yet his hopes were tempered by our history with slavery. Readers are often exasperated by Jefferson’s attitude, his tone of riding serenely above our problems, “trusting in the wisdom of the people,” and so on. (They overlook other instances when Jefferson speaks pessimistically.) In Lincoln’s writing there are misgivings about whether America can deal with the problem of slavery. We can appreciate that. The founders did not express so many misgivings. Unanticipated events made slavery a bigger problem than they thought it would be. Lincoln faced this, and that makes him more relatable.

JF: It’s interesting, however, that some speak of systemic racism as a blight on American society today yet seem to discount the struggle of Lincoln and the Republican Party in the mid 19th century to limit the spread of slavery, almost as if its death was inevitable. This minimizes the role of statesmanship and human agency in history.

DT: Slavery had become embedded, not just in the South, obviously, as a social institution, but even in the northern economy, with factories producing cheap cloth for slave clothing and so on. It was not, I think, as big a part of the American economy as some want to claim—yet it represented a significant economic interest. It’s remarkable that we actually got rid of it.

ET: Some years ago, I read about the Moravians of North Carolina. I was struck by how they changed after migrating to the South from Pennsylvania, where anti-slavery sentiment prevailed. They settled among slaveholders, and, realizing they had a lot of work to do to erect a new community, they decided to rent the slaves of their neighbors. This corrupted the community. Whereas in the beginning, they invited the enslaved people into their Christian fellowship, eventually they had to build them a separate church.

DT: Yes, slavery was very corrupting.

JF: And don’t forget the attitudes in the north. Look at what happened after the Battle of Gettysburg, with the draft riots that turned into race riots.

Next week, the conversation continues, as Fornieri and Tucker discuss the historical controversies regarding Lincoln’s actions and purposes as a statesman.