Lincoln’s Enduring Relevance

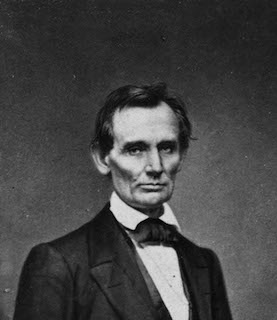

Most teachers of American history and government admit to a fascination with Abraham Lincoln. Because he so clearly explains American political principles, many teachers use Lincoln’s words as touchstones throughout their courses. Yet many of the same teachers find Lincoln’s motives somewhat elusive.

We asked three teachers who attended a 2022 TAH multiday seminar in Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield, Illinois—Charles Martindell, Justin Crews, and Brett Van Gaasbeek—to explain why Lincoln’s writings spoke to them and their students. All three are graduates of the Master of Arts in American History and Government program. All say their MAHG studies persuaded them to teach through primary documents. All teach more of Lincoln’s writings than those of any other author.

Lincoln Explains Our Political Principles

“Before MAHG, “I didn’t realize the depth and continual relevance of Lincoln’s thought,” said Charles Martindell, formerly a teacher at Pleasant High School in Marion, Ohio, and now a TAH staff member. Like Crews and Van Gaasbeek, he learned of Lincoln’s Fragment on the Constitution and Union in MAHG and began showing it to students when they first read the Constitution. In this private note to himself, Lincoln asserts that the Constitution was written to protect the principles articulated in the Declaration of Independence, especially the principle of human equality.

“In a sense, Lincoln’s thoughts on the founding are more important”—or at least more accessible to students—”than the founders’ thoughts on the founding,” Martindell said. “Lincoln viewed the founding in hindsight,” at a time when the founders’ assertion of human equality had been called into question. “Slavery had become far more entrenched, and racism much more enshrined in the science of the day than the founders anticipated.”

Martindell’s MAHG degree qualified him to teach a dual enrollment course on “Democracy in America.” Students earned college credit for the political theory course through Ashland University. “We spent a few weeks of the course examining the question, ‘What did the founders mean when they said that all men are created equal?’ After all, many of the founders held slaves.” Among other documents, students read Chief Justice Roger Taney’s majority opinion in the Dred Scott case, Alexander Stephens’ Cornerstone Speech, and Lincoln’s Peoria speech.

These documents yield three alternate interpretations of the founders’ meaning, Martindell said. “Taney claimed that the founders said one thing, but meant another. What they really meant was people of their own kind were created equal. Alexander Stephens argued that the founders literally meant what they said—but they were wrong. Lincoln’s view was that the Founders meant what they said. And they were right.”

One might easily arrive at Taney’s interpretation, Martindell said, if one neglected to do “much research on the founders. Lincoln did the research.” To demonstrate the founders’ “hostility” to slavery, the Peoria speech cites the 1787 Northwest Ordinance; the refusal to use the word “slave” or “slavery” in the text of the Constitution; and five different acts of the earliest Congress to restrict or end the international slave trade.

“In fact, it’s remarkable”—given the rapid expansion of slavery, despite the founders’ expectations—”that Lincoln . . . could look back at the founding with reverence, and with hope” that the principle of equality would one day lead to slavery’s extinction.

Lincoln’s Rational Leadership

Justin Crews‘ fascination with Abraham Lincoln began at an early age. He grew up in Lincoln City, Indiana, near the site of Thomas Lincoln’s 160-acre homestead, where Lincoln grew from a child of seven into a youth of 21. At one time, Crews’ parents owned an acre of this homestead site; it was seized by eminent domain when the decision was made to create the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial. As the centerpiece of the memorial, the National Park Service created a “working pioneer homestead,” where Crews’ mother took a job as an historical interpreter. “I spent my summers with her, dressed in 1820s costume, learning and demonstrating how to use tools Lincoln used as a boy. It was there that Lincoln learned to split rails. I split a few myself—two or three a day, whereas Lincoln split about 300.”

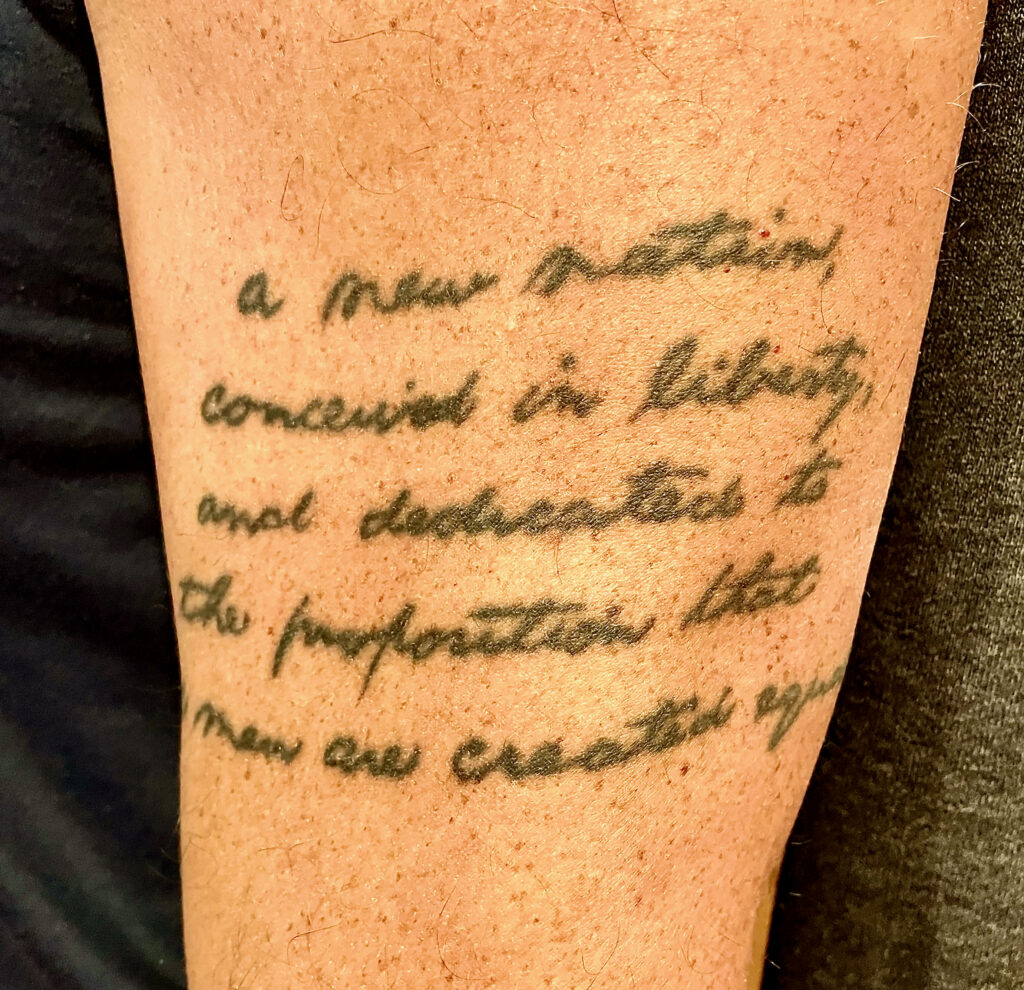

Today Crews teaches US history, from the European discovery and settlement through the Civil War and Reconstruction, at Troy Junior High School, on the western border of Ohio. “Students know about me and Lincoln; they know they will get a heavy dose of Lincoln when they enter my classroom,” says Crews. Photos of Lincoln and quotations from his speeches and writings hang on its walls. The eighth graders have had no experience reading primary documents before entering Crews’ class, so they struggle a bit to understand Lincoln’s Fragment on Constitution and Union—his comparison of the Declaration to a painting of an “apple of gold” and of the Constitution to a silver frame protecting it. To make the point, Crews often rolls up this sleeve to show them a key clause of the Gettysburg Address, replicating Lincoln’s own handwriting, tattoed on his upper arm:

a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal

“That’s Lincoln’s tribute to Jefferson and the principle of equality, which is the apple of gold,” Crews says. Showing off this tattoo “makes a difference to students. When they see a teacher has a passion for history, they become interested.” He also asks students to read excerpts of Lincoln’s Lyceum Address, including this passage:

At what point shall we expect the approach of danger? By what means shall we fortify against it? —Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant, to step the Ocean, and crush us at a blow? Never! —All the armies of Europe, Asia and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest . . . could not by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge, in a Trial of a thousand years.

At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad. . . . As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.

In the same speech, Lincoln gives his prescription for avoiding national suicide:

Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our future support and defense. Let those materials be molded into . . . sound morality, and . . . a reverence for the Constitution and laws.

Crews hopes his students come to see Lincoln as the preeminent exemplar of “unimpassioned reason.” Lincoln could “separate his personal feelings from what he thought needed to be done.” He could “read the pulse of the people and then pull them to where he felt they needed to be. He didn’t get them all the way over. But he was able to shift the national conversation through his reason, and through his ability to speak to the people in ways that they could understand.”

Lincoln’s Rhetoric

Lincoln’s ability to reach ordinary citizens with his words makes him “the easiest author to teach,” says Brett Van Gaasbeek. “He’s brilliant, and he’s folksy, and folksy translates to kids, especially to those from backgrounds similar to his.” Van Gaasbeek teaches at Cincinnati Northwest High School, in what was once a thriving working-class neighborhood but now houses those left behind by a changing job market.

“It’s an interesting place to teach, because the student population is so diverse” —about 50% Caucasian; 40% African American, and 10% Asian or Hispanic. Many are immigrants. Outside of school, most care for younger siblings or work long hours in service jobs. “It’s hard to interest them in the issues debated by Clay, Calhoun and Webster. The don’t even see the relevance of William Lloyd Garrison or Frederick Douglass. For them, the struggle over slavery is long past. They come alive when we discuss Martin Luther King and Malcolm X.”

Nevertheless, Lincoln gets through. Van Gaasbeek spoke of recently teaching Lincoln’s Lyceum Address to his advanced placement and dual credit students. He’d begun by setting the context. “Lincoln was born in 1809, and gave this speech when he was 29. Where does this put him in our history?” A student replied, “well, he’s not a founding father.” Van Gaasbeek then asked an avid follower of football to list the greatest quarterbacks, starting from today and continuing back to the 1980s. After struggling to come up with the earlier stars, the student agreed that each generation must have learned from their predecessors. Van Gaasbeek drove home the point. “Great quarterbacks watch what other guys do. What is Lincoln saying about our political institutions? If the perception is we’re not getting any better, are we failing to train the next generation?”

When students reached Lincoln’s line, “We must live through all time, or die by suicide,” one said, “He was speaking in 1838; the Civil War began in 1861. Was he predicting this war 23 years beforehand?” Another said, “This problem Lincoln’s talking about—is that why people were so upset about January 6?”

In the next weeks, these students would read the Peoria and House Divided speeches, excerpts of the Lincoln-Douglass Debates, the First Inaugural, Gettysburg Address, and the Second Inaugural. Afterwards, Van Gaasbeek would ask them whether Lincoln was consistent in his view of abolition. “From 51 students, I’ll get 51 different responses,” ranged at slightly different points in the middle of a continuum between avidly in favor of abolition and uninterested in it, Van Gaasbeek predicted. They will all understand something about Lincoln and his priorities, even though they’ll reach different conclusions.

Van Gaasbeek thinks Lincoln speaks to students today much as he spoke to citizens of his own time, making each feel a connection to him. “He handled the greatest crisis this nation has ever faced, speaking in a way that made people feel better about it.” As the war neared its end, Lincoln delivered the Second Inaugural Address, telling those on both sides of the conflict that the bloodshed they suffered was needed to “cleanse them all of the sin of slavery. He doesn’t cast blame—except to blame us all.” Van Gaasbeck believes that most of those listening must have felt convicted, and readier to forgive the other side—because Lincoln goes beyond rhetoric to poetry that changes hearts. “What a testament to a leader who for four years has himself been blamed by critics on all sides for causing a terrible war. . . . Even on his worst day, Lincoln is the person we would all aspire to be.”