LOVE CANAL: I WILL NEVER BE QUIET AGAIN

Lois Gibbs never dreamed of becoming a political activist. In April 1978, Lois and her husband lived a traditional life in Niagara Falls, NY. Lois stayed home, caring for their home and her two young children. Her husband’s job in a local chemical plant provided a steady income. They liked the neighborhood. Their kids’ school was three blocks from their home, and the Niagara River flowing just beyond the school created an idyllic scene they enjoyed visiting. The neighborhood children enjoyed playing in an open field next to the school. Until the day she sat down with a cup of coffee, a copy of the Niagara Gazette, and read Michael Brown’s report on toxic chemicals in the area, Lois felt safe in her home and content with her neighborhood.

Brown’s article described some residents’ concerns about chemicals seeping through their basement walls and into the open field their children liked to play in. At first, Lois did not realize Brown’s story described her neighborhood. When she did, she wondered if this was why one of her children was sick so often. Over the next several years, Lois acted on her concerns. She and other “housewives turned activists” organized their neighbors and pressured government officials to pay for the relocation of over 1000 families exposed to dangerous chemicals in the Love Canal neighborhood of Niagara Falls. On August 2, 1978, New York Governor Hugh Carey announced the first relocations. Five days later, President Jimmy Carter authorized using federal funds for Love Canal’s clean-up and the cost of relocating some of the families, the first such use for an emergency not caused by a natural disaster.

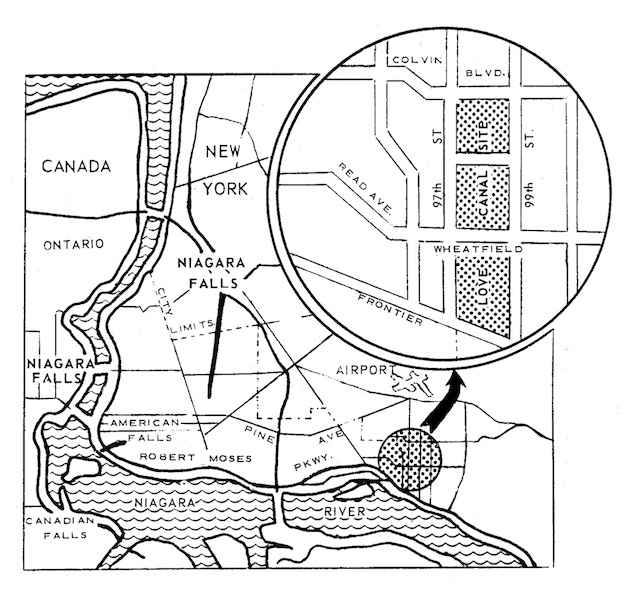

Love Canal’s history is rooted in a vision of industry and the environment very different from that which emerged in the 1970s. In 1892, William Love proposed building a canal linking the Niagara River’s upper and lower sections, thus providing hydroelectric power for a model community he planned to build. Inadequate funding and Nikola Tesla’s proof that alternating current (AC) carried over long distances was viable killed Love’s plans. All that remained of the original concept was a mile-long trench up to forty feet deep. The trench was used as a landfill until the Hooker Chemical Company purchased the land in 1942 and began using the trench to store steel drums containing chemical waste. Hooker put eighty-eight chemicals totaling twenty thousand pounds in the canal between 1942 and 1953. When Hooker Chemical sold the land to the local school board in 1953 for $1, they insisted that the district waive any future claim against the company for damages caused by the toxins.

Hooker officials installed a clay cap over the waste-filled trench. Company officials may have believed the cap would protect the neighborhood. In any case, the board constructed an elementary school on the site. A school for 400 students opened in 1955. The district sold surrounding land to homebuilders, and during the next 10-15 years, over 1000 homes were built. Niagara County experienced several seasons of heavy winter snow and drenching spring rains in the mid-1970s. Construction of the school and the heavy rains destabilized the clay cap, eliminating any protection it may have afforded Love Canal’s families. Gazette reporter Michael Brown began investigating toxic chemicals in Niagara County in 1977. He knew neighbors complained about foul odors in the area. Since the area had many chemical plants, residents assumed the chemical smells were the price they had to pay for good-paying jobs and stable communities. He encountered resistance from Hooker Chemical and some of the Love Canal residents. Hooker was one of the largest employers in the area. Some residents feared that negative publicity about the company might lead to lost jobs or Hooker’s reduced investment in Niagara Falls.

Brown decided to canvass the Love Canal neighborhood, seeking first-hand accounts of conditions there. One of the first families he met was Timothy and Karen Schroder’s, whose daughter, born in 1968, suffered from several congenital disabilities, including partial deafness, a hole in her heart, and cognitive disability. The Schroeders assumed it was the little girl’s fate and not underground chemicals that explained their daughter’s condition, until Karen looked at her backyard one day and saw their in-ground fiberglass pool protruding two feet out of the ground after a heavy rainstorm. When they attempted to replace the pool two years later, “yellow chemical water” flooded the space. The Schroeders wondered then if the chemicals in the area had caused their daughter’s congenital disabilities.

Brown’s reporting inspired Lois Gibbs to begin her own survey of neighborhood conditions. She found what seemed to her a high rate of miscarriages, congenital disabilities, and childhood illnesses from asthma to leukemia. She contacted local public health officials, who dismissed her concerns. When Lois attended an organizing meeting for what became the Love Canal Homeowners Association (LCHA), the group elected her chairperson. She had only a high school education and was not an expert on chemical waste, but she remained calm in tense situations.

In 1978, public health officials conducted a health survey. They took blood samples and concluded that the residents closest to the trench and those with children under two must be relocated immediately. Governor Hugh Carey came to Love Canal in early August and announced that approximately two hundred families were eligible for immediate relocation. President Carter’s authorization of federal funds lent additional financial support.

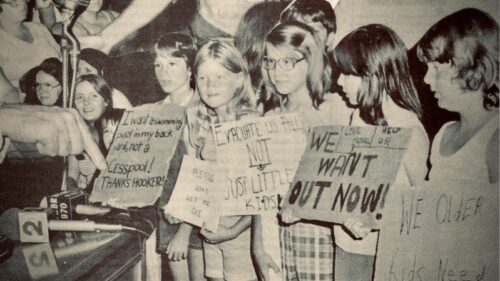

The initial relocation decision outraged residents outside the designated relocation perimeter. They saw little difference between families with two-year-old children and those with slightly older children. Some houses were only a few yards from those moved. Two organizations, the Love Canal Renters Association (LCRA) and the Ecumenical Task Force (ETF) led by Sister Margeen Huffman, joined forces with the LCHA to pressure state and federal governments to fund the relocation of all families in the Love Canal neighborhood.

In January 1979, Dr. Beverly Paigen released the results of her study of Love Canal residents, which found a high rate of miscarriages and congenital disabilities. She supported relocation. In May 1980, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced that a chromosome sampling of residents suggested chromosomal damage and an increased risk for cancer. Residents met with EPA officials. Some neighbors surrounded the building where the officials were meeting with LCHA members. Some of the angriest neighbors in the crowd suggested that the officials be held hostage until they agreed to support the relocation of all Love Canal residents. Lois Gibbs diffused the situation by telling the crowd that the officials were supportive, although she knew the officials could not authorize anything other than what the EPA had already agreed to.

Two days following this tense standoff, New York announced funding for temporary housing for 800 families while the state developed permanent solutions. In October 1980, President Carter traveled to Love Canal to announce a second authorization of emergency funds to assist clean-up efforts and relocation. He also signed the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA), nicknamed the “Superfund” Act.” The Superfund Act authorized the EPA to relocate Love Canal families and seek compensation for costs from those causing the damage. In 1994 and 1995, Hooker’s parent company Occidental Oil agreed to pay New York State and the federal government over $225M in compensation for clean-up and relocation costs.

Lois Gibbs continues to be active in the environmental movement. She has shifted her focus from chemical waste to fracking. Still, she argues that her primary focus has always been families and the earth. American history and government teachers teach about social reform movements. I used Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) as an excellent example in my classroom. Candace Lightner lost her 13-year-old daughter to drunk driving but turned her tragedy into a nationwide campaign for stricter enforcement of drunk driving laws. MADD has successfully shifted the conversation around drunk driving. It is now socially unacceptable. Neither Gibbs nor Lightner were eager political activists. They became active when their families experienced tragedies that affected others and required political solutions. They chose to speak out and do what they could to persuade government officials to act.

Lois Gibbs helped Americans see that the chemicals we put in the air and the soil can devastate families. My family may be one of them. Our twin sons were born with significant congenital disabilities that we believe stemmed from a 1990 chemical spill my wife experienced when she was twelve weeks pregnant. Researching and writing this blog uncovered some painful memories.

So, I salute Lois Gibbs Candace Lightner and others like them. They refuse to sit in silence, wring their hands, and say “well, what can you do. I’m just one person.” They chose to take a stand, which is the kind of courage I think American history and government teachers want to instill in their students. In the words of Marie Pozniak, an ally of Lois Gibbs in the Love Canal Homeowners Association, “before the crisis, I was quiet … I will never be quiet again.”

Ray Tyler was the 2014 James Madison Fellow for South Carolina and a 2016 graduate of Ashland University’s Masters Program in American History and Government. Ray is a former Teacher Program Manager for TAH and a frequent contributor to our blog.