Lynching: 1917 Protest Parade Ignites Debate

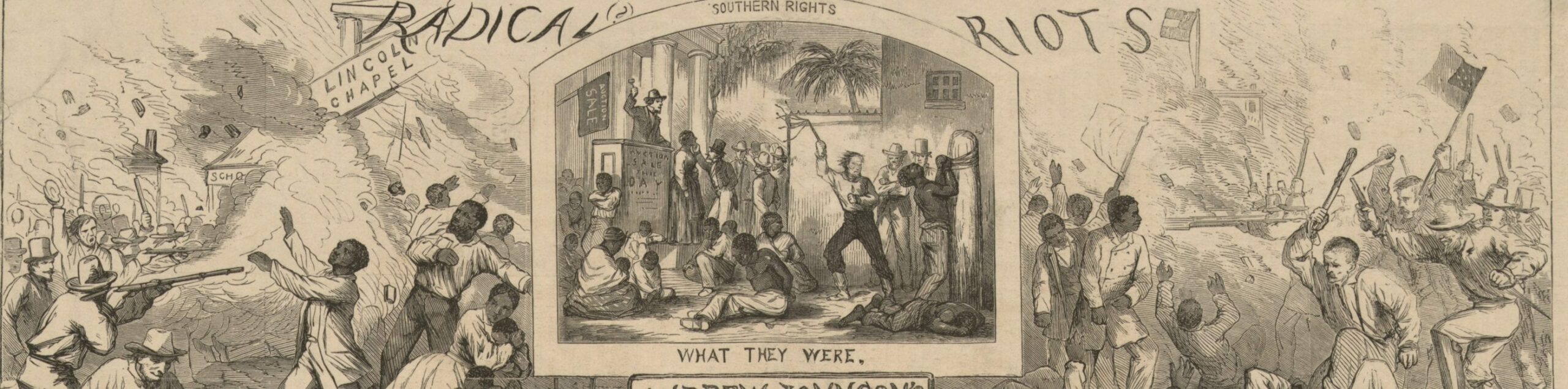

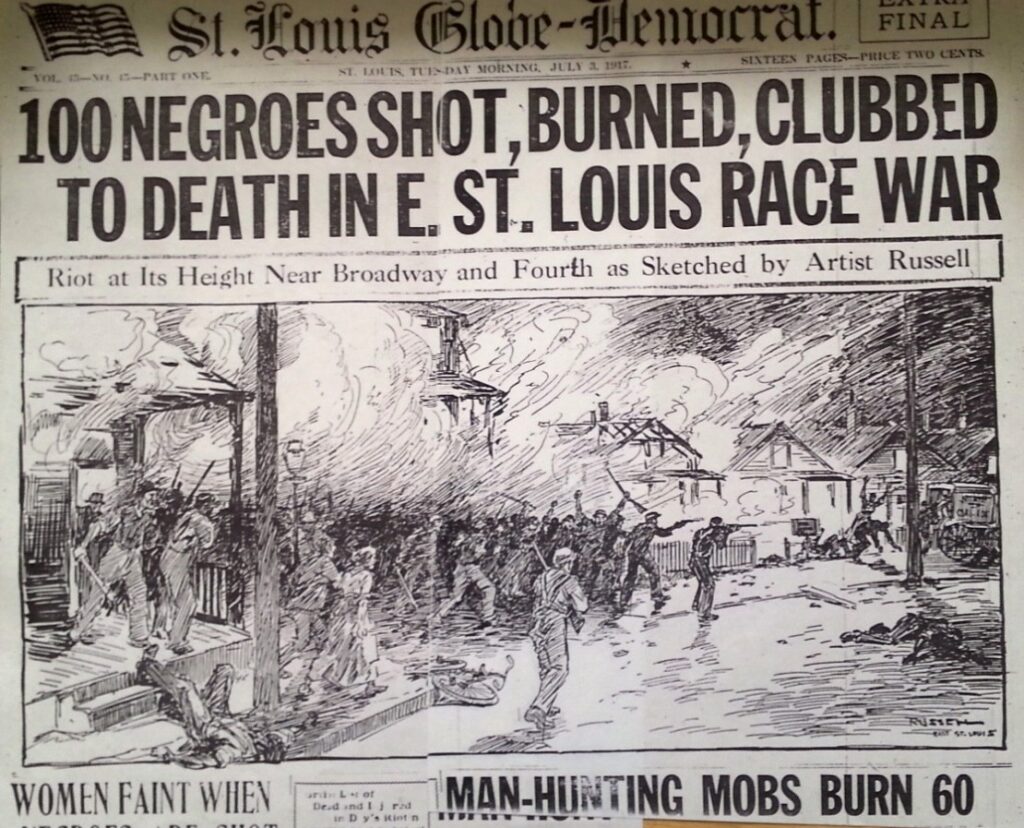

In the summer of 1917, a riot erupted in East St. Louis, Illinois, a small city situated across the river from St. Louis, Missouri. White marauders attacked the homes of black citizens, setting fire to them and in some cases burning families alive in their own homes. The riot resulted in hundreds of African American deaths, while achieving its presumably intended effect of driving an estimated 6000 black citizens out of the city and across the river into Missouri.

Race Hatred Inflamed by War-time Migration

Ironically, the violence terrorizing black citizens erupted at a time when President Wilson was urging Americans to support the Allied effort in Europe to “make the world safe for democracy.” In fact, the US entrance into World War I helped to trigger the massacre. Large numbers of Southern blacks migrated to East St. Louis to work in munitions factories supplying the war effort. As a result, the black population of the city, counted at 6000 in the 1910 census, had nearly doubled. While resentful of the housing competition, many whites were outraged by competition in the labor market. Animosity toward the black migrants surged in the spring of 1917, when workers at the local Aluminum Ore Company who walked out on strike were replaced by African Americans.

Random attacks began in late May, with some African Americans being pulled off of streetcars and beaten. When, on Saturday, July 1, a drive-by shooter attacked black homes, armed African Americans gathered and shot at a car resembling the attacker’s. Unfortunately, the driver and passenger they killed were police detectives sent to investigate the earlier shooting. This led to a Sunday morning meeting of angry white citizens, who dispersed as a mob, attacked black pedestrians, and streamed into black housing areas to set fires.

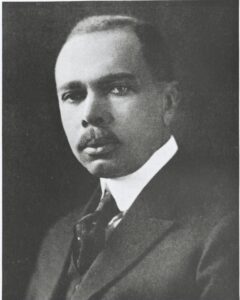

Johnson Helps NAACP Organize Opposition to Lynching

Eighteenth months before these events, James Weldon Johnson had begun working for the NAACP as its first Field Secretary. When offered the job, Johnson was a well-respected writer and intellectual in what would come to be called the Harlem Renaissance. Earlier in his life he’d worked as a school principal, lawyer and newspaper editor in his home town of Jacksonville, Florida; a lyricist for New York’s musical theater; and a Republican-appointed diplomat in Venezuela and Nicaragua. Offered a staff role in what was then a tiny organization bent on huge reforms to American society, he realized “that every bit of experience I had had . . . was preparation for the work I was being asked to undertake,” as he wrote in his 1933 autobiography, Along This Way.

He began at once helping to promote the organization’s case that it was time to give African Americans “common equality under the fundamental law of the United States” and “the impartial application of that law.” He hoped to persuade Americans “that democracy stultified itself when it barred men from its benefits solely on the grounds of race and color.” But he expected virulent opposition. “Communists, who advocate and work for the overthrow of the entire governmental system, run no such risks as the Negro ‘radical’ who insists upon the impartial interpretation and administration of existing law,” he would later write.

In 1916 the NAACP membership comprised about equal numbers of white and black members. Johnson began traveling through the south, recruiting members among blacks who had suffered years of Jim Crow. Soon he began investigating southern lynchings, traveling first to Memphis, site of the burning alive of Ell Persons, a black man accused of murder. Looking down on a pile of ashes from which the victim’s bones had already been picked as grisly souvenirs, Johnson imagined the scene:

A lone negro in the hands of his accusers, who for the time are no longer human; he is chained to a stake, wood is piled under and around him, and five thousand men and women, women with babies in their arms and women with babies in their wombs, look on with pitiless anticipation, with sadistic satisfaction while he is baptized with gasoline and set afire. The mob disperses, many of them complaining, ‘They burned him too fast.’ I tried to balance the sufferings of the miserable victim against the moral degradation of Memphis, and the truth flashed over me that in large measure the race question involves the saving of black America’s body and white America’s soul.

Responses to Lynching in North and South

Memphis authorities arrested African Americans whom they accused of fomenting the riot. To provide legal defense for the accused, the NAACP hired Charles Nagel, who had served as Secretary of Commerce under President Taft. They also raised money for the relief of those burned out of their homes.

While southern leaders denied the realities of lynching, some northern leaders deplored the lawlessness. After the massacre in East St. Louis, Congress passed a resolution to investigate what had happened. Congressmen from both Missouri and Illinois reviewed the horrifying testimony of witnesses. Illinois Congressman Rodenberg declared, “the plain, unvarnished truth of the matter . . . is that civil government in East St. Louis completely collapsed at the time of the riot. . . . It is impossible for any human being to describe the ferocity and brutality of that mob.”

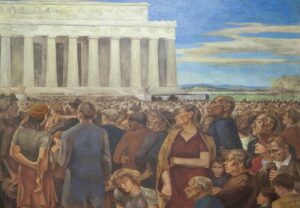

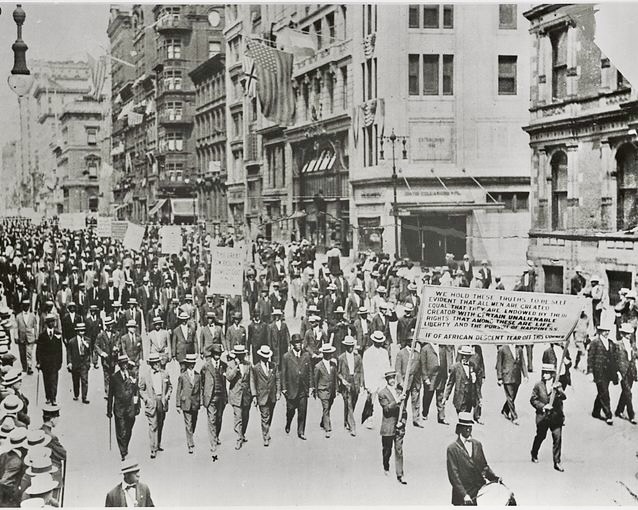

A Powerful Protest Demonstration

When the Harlem branch of the organization called for a mass meeting at Carnegie Hall to protest the massacre, Johnson suggested a more effective demonstration: a silent march down Fifth Avenue, involving protesters from all over Greater New York. A committee of clergymen and other leading citizens rallied black citizens in the New York area. They organized a coordinated procession of nine or ten thousand African Americans on Saturday, July 28. Marchers strode “silently . . . to the sound of only muffled drums.” A crowd of silent New Yorkers, some “with tears in their eyes,” watched the marchers pass in groups: first, children dressed in white; then, women dressed in white; finally, men in dark clothing. Some carried banners that read:

MOTHER, DO LYNCHERS GO TO HEAVEN?

GIVE ME A CHANCE TO LIVE.

TREAT US SO THAT WE MAY LOVE OUR COUNTRY.

MR. PRESIDENT, WHY NOT MAKE AMERICA SAFE FOR DEMOCRACY?

Black boy scouts distributed flyers to onlookers that explained the march as a call for justice and Christian decency.

The Dyer Anti-Lynching Act

In 1919, Johnson began lobbying Congress to pass a federal law against lynching. He worked with Republican Representative L. C. Dyer of Missouri, whose district included many of the black residents of St. Louis. In the spring of 1921, Dyer introduced a bill “to assure to persons within the jurisdiction of every state the equal protection of the laws, and to punish the crime of lynching.” Johnson, now Executive Secretary of the NAACP, began calling on “every man in Congress who was interested in the bill or who, I thought, could be won over to it.” Meanwhile NAACP members from across the country sent letters imploring Congressmen to act. Johnson supplied the bill’s sponsors with thirty-three years of data on lynching, including findings refuting the claim of Southern congressmen that most lynchings were spontaneous eruptions of anger over the rape of white women. The NAACP’s figures showed that fewer that 17% of lynching victims had ever been accused of rape. Many victims were accused merely of “talking back” or other behaviors whites regarded as impudence. On January 10, 1922, the anti-lynching bill passed the House by a vote of 230 to 119.

In the Senate, the bill faced a much tougher fight. There, many expressed Constitutional objections, arguing that all matters of criminal justice belonged under state jurisdiction. The NAACP pressed ahead, securing endorsements of the bill from 24 state governors and 39 city mayors; from college presidents, lawyers and judges; and from leading churchmen. Johnson testified before a Senate hearing, arguing that lynching was a crime beyond murder; it was a mob substituting its own will “for the due processes of law guaranteed by the Constitution to every person accused of crime.” As Republican Senators offered ambivalent assurances of support, Johnson realized that passing the bill would require outmaneuvering Southern opposition. Indeed, southern Democrats slowed the bill’s passage through committee, filibustered it when it its sponsors tried to introduce it on the Senate floor, and threatened to obstruct any further legislation during the session if the bill were not withdrawn. Johnson’s Senate allies gave into this pressure—too easily, he felt. They had acknowledged that, if brought to a vote, the bill would pass.

Impact of the Congressional Debate Over Lynching

A decade later, Johnson reflected that although the Dyer Anti-Lynching bill did not become law, “it made the floors of Congress a forum in which the facts were discussed and brought home to the American people as they had never been before.” He attributed the sharp decline in lynchings during the 1920s and 1930s to the publicity given the bill. By shaming Southern citizens and their leaders, the debate over lynching led to efforts to restrain mob violence. Racist murders as mass spectacles grew less frequent.

Anti-lynching legislation was introduced in Congress on 200 subsequent occasions, failing to pass each time. Finally, on March 29, 2022, the Emmet Till Antilynching Act of 2022 was signed by President Biden, making lynching a federal hate crime.

Source: James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way (1933), published by Da Capo Press in 2000.