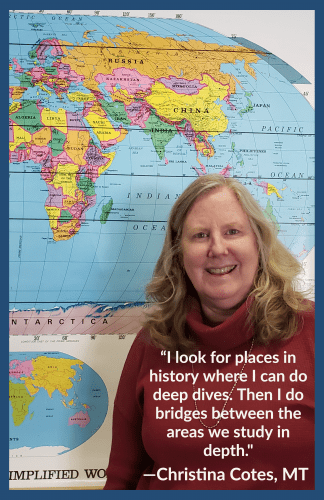

Meet Our Teachers: Christina Cote

“I know my students pretty well by the time they are seniors,” says Christina Cote. She teaches every history and government course they take between 7th and 12th grade. In Gardiner, Montana, a town of less than 1000 people on the northern border of Yellowstone National Park, Cote is the public-school face of social studies. She is also Montana’s 2020 winner of the Gilder Lehrman Teacher of the Year award.

The pandemic and the move to remote teaching gave Cote time to apply for the award (she was not, for example, spending afternoons coaching the speech and debate team and Saturdays driving them to remote meets). The lesson plans she submitted with her application showed how she adapted study of primary documents to the online platform. “How would I teach the Civil War without falling back on boring lectures?”

Fortunately, all of her students have Chromebooks. She introduced them to online archives of old newspapers, where they found casualty data on days after Civil War battles. She asked them to read letters and diaries of soldiers in online libraries. Her students came to understand the battlefield experience and hardships of those fighting our nation’s bloodiest war.

From the Long Human Story, What History Should Students Learn?

Whether teaching remotely or online, Cote manages six different preparations. She teaches ancient world history to 7th and 8th graders, modern world history to 9th graders, US history to juniors, and government to seniors (in the latter course, some students do extra work for AP credit). Sophomores may opt to take AP European history as an elective. Each class is a small group of 12 or 13 students.

Whether teaching remotely or online, Cote manages six different preparations. She teaches ancient world history to 7th and 8th graders, modern world history to 9th graders, US history to juniors, and government to seniors (in the latter course, some students do extra work for AP credit). Sophomores may opt to take AP European history as an elective. Each class is a small group of 12 or 13 students.

“I know the scope and sequence not only of each course, but of the whole secondary social studies curriculum,” Cote said. Choosing—as all history teachers must—which parts of history to cover and which to leave out, she considers what students most need to learn. Since “history is much more meaningful when you look at the details,” Cote selects key points in history for “deep dives. Then I do bridges between the areas we study in depth.”

In high school, she teaches history thematically. “This keeps me from just going from one war to the next war to the next. Teachers can easily do that, forgetting that there were also women living during the history, and marginalized groups, and people making art. When you teach thematically, you can link events across time.”

Her US history class covers four themes, one each quarter. First, they study the expansion of the nation—learning “why the borders of the US are what they are” and scrutinizing episodes like war with Mexico in light of the Monroe Doctrine. Next, they consider the problem of “inequalities” in a nation founded on the principle of equality. The third quarter addresses economic history, covering basic economic terms, the populist and progressive responses to industrialization, the rise of unions, and the Grange Act. “We also simulate the 1920s stock market: They buy and sell stock, then they lose all their money because I close the banks.” Fourth quarter is entirely devoted to American wars.

Finding Colleagues Through Summer Teacher Programs

To meet colleagues in her content area, Cote seeks out summer professional development opportunities. “One of the coolest professional experiences I’ve ever had was the 2007 Presidential Academy.” This forerunner of Teaching American History, designed by Ashbrook and funded by a Department of Education grant, was a three-week movable feast of primary document study and historic site visits. One teacher from each state in the nation was selected for a seminar that moved from Philadelphia to Gettysburg to Washington, DC, exploring the Founding, the Civil War, and the Civil Rights movement through primary documents. “I don’t know how many times I’ve shared with my students things I learned during that experience—through interaction with other teachers, from visiting historic sites, or from the scholars who taught us. With Professor Lucas Morel, we went through most of The Federalist papers. They really set a high standard—making us want to come back and set a high standard in our own classrooms.”

During the next academic year Cote applied for and was awarded a Madison fellowship. She used it to enroll in the new Master of Arts in American History and Government program, grateful for an opportunity to study American history during the summer. “I wanted that high academic experience again,” Cote said.

How Students Learn to Read for Every Word

“The program helped me use primary documents to make history real. I was doing it before, but I have such a stronger commitment to that now. I’m not going to ask students to read every page of every Federalist paper, but having gone through every word of those texts with Dr. Morel, I’m more comfortable guiding students through excerpts.”

Cote introduces students to primary documents in the 7th grade. “We read a large part of Pericles’ funeral oration. I give each student a six-to-ten-line segment of the speech, asking them to read it and think about why Pericles would have said those words, given the events of the Peloponnesian War. I let them wrestle for the meaning on their own, using their Chrome books to look up unfamiliar vocabulary. Then I ask them to ‘translate’ their passage into their own words.

“Then the kids recite what they’ve written in sequence, going through the whole speech. This way the kids learn from each other.”

Oral performance of texts makes good sense to a highly successful debate team coach (Cote has led Gardiner’s team to 16 state championships). Sometimes she asks students to read out loud in unison. “Because I ask them to read with expression, they must think about every word.” In US history, students have enjoyed reading aloud correspondence between Abigail and John Adams, not only the famous letter asking John to “remember the ladies,” but another in which Abigail recounts a conversation with a neighbor about a black child attending a newly opened school in the Adams’ hometown of Quincy. The neighbor reports that some students object to the child’s presence. Abigail reproduces their dialogue:

“Pray, Mr. Faxon, has the Boy misbehaved? If he has let the Master turn him out of school.” – “O no, there was no complaint of that kind, but they did not choose to go to School with a Black Boy.” . . . – “Did these Lads ever object to James playing for them when at a dance? How can they bear to have a Black in the Room with them there?” – “O it is not I that object, or my Boys. It is some others.” – “Pray, who are they? Why did not they come themselves?”

Strategies like reading in unison help students at any level slow down and appreciate a text’s meaning. But as students move into high school, they also begin writing research papers, using documents to support arguments.

The Skills, Knowledge and Outlook Citizens Need

This year, she felt her students needed instruction in media literacy. Following an election unusually colored by conspiracy theories, Cote and the upper school English teacher arranged for a philosophy professor from Montana State University to speak with the 10th, 11th, and 12th graders about how to evaluate the credibility of news sources. After working through exercises to apply the philosophy professor’s advice, the students presented what they had learned to the junior high. “I watched a senior who was not college bound speak persuasively to the younger students, asking them to think carefully about bias in the news,” Cote said proudly.

Cote also insists on a basic level of civic literacy. “I require all my seniors to take a citizenship test. It’s a hundred questions, mostly drawn from exam taken by immigrants applying for citizenship. I let students re-take the test as many times as necessary, but they must get a perfect score to pass. Because I have this reputation, they know to expect the test. It’s very rare that they have to take it more than twice.”

Cote feels privileged to spend six years with students, helping them become “thinking citizens.” She hopes they leave her classroom understanding their roles as citizens. “We are all part of this democracy, and we can’t keep it, unless they play their role.”