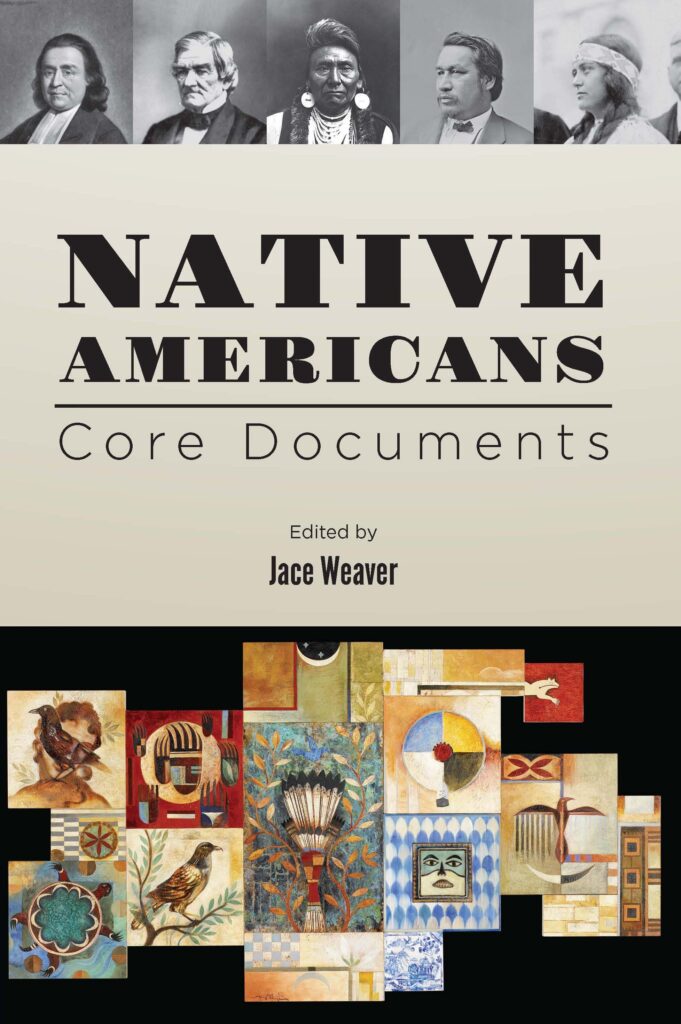

Professor Jace Weaver‘s recently published core document volume, Native Americans, traces 400 years of the uneasy relationship between the indigenous inhabitants and later claimants to the land that became the United States of America. The volume’s forty-six document excerpts introduce readers to a diverse cast of American Indians, befriending, resisting and enduring successive generations of European Americans moving across the continent. Weaver, who is the Franklin Professor of Native American Studies and Religion, former director of the Institute of Native American Studies, and Adjunct Professor of Law at the University of Georgia, is an Honored Visiting Professor in the Master of American History and Government program at Ashland University. His many publications include The Red Atlantic: American Indigenes and the Making of the Modern World, 1000-1927 (2017); Other Words: American Indian Literature, Law, and Culture (2001); That the People Might Live: Native American Literatures and Native American Community (1997); and the award-winning American Indian Literary Nationalism, written with Robert Warrior, Craig Womack, and Simon Ortiz (2007). Recently we asked Professor Weaver to answer some questions about Native American history and the legal status of American Indians.

Your collection is called Native Americans; yet in your introduction you point out that the term Native American is a relatively recent invention, and not necessarily preferred by all the people to whom it refers. What term do you use?

I use a number of terms, depending on the context. “American Indian” is an older, more rural, more reservation-based term, stemming from Columbus’s misunderstanding. He never saw North America, but he called those he encountered in the Caribbean Indios, because he thought he had reached the Indies, the islands off the coast of Asia. Yet the term stuck. “Native American” is a post-World War II term that grows out of the experiences of urban Indians who sought each other out for fellowship. They came from a range of tribes, but realized that they had a commonality of history and experience. So they created friendship centers open to any “Native American.”

I try not to use “Native American” in contexts prior to World War II. Most often I use simply “Native” as a generic designation. To insist on Native American, because you think it’s more polite, can create problems. An editor I worked with insisted on this, resulting in awkward terms like the “Apache Native Americans.”

I assume most American Indians identify primarily with their tribes; but do they also enjoy American citizenship?

All Indians have been citizens since 1924, when the Indian Citizenship Act was passed, ensuring that the one third of Native Americans who had not yet attained citizenship through some other means would be citizens. Indians who are enrolled as citizens of federally recognized tribes are accorded a kind of dual citizenship: they are subject to the tribal government, but the tribe, although called a sovereign nation, is subject to the superior sovereignty of the federal government. Tribal recognition came initially through treaties; today it can happen by act of Congress or through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, if tribes apply for federal recognition. The latter is a long and convoluted process.

The federal government currently recognizes a government-to-government relationship with 574 tribes. Tribal nations are unique in our federal system. The Constitution gives Congress power over them, a power that has been interpreted by the courts as “plenary,” meaning “complete.” In the past, this allowed the US government to do to Indians what they could not do to any other citizen. Theoretically, it also created obligations the federal government owed the tribes.

Is dual citizenship granted only to those who live on reservations?

No. In fact, the majority of Native Americans today live in cities, not on reservations, as a result of certain post-World War II policies. Since the closing of the frontier, federal Indian affairs have been discussed in two ways, both of which show up in the volume. Some speak of “solving the Indian problem”—that is, dealing with the fact that Indians still exist and hold claims based on treaties. Others speak of “getting out of the Indian business,” dismissing the problem.

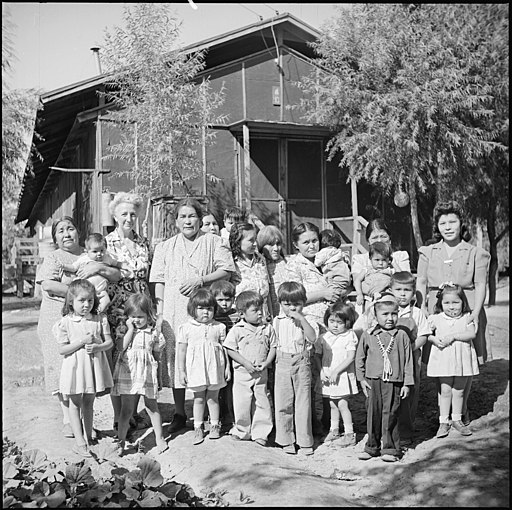

After World War II, Congress tried to dismiss the problem by creating the Indian Claims Commission, which was going to settle all Indian claims once and for all. That didn’t work. Then in 1953 Congress passed laws ending federal recognition of numerous tribes and their government-to-government relationships with the United States. Indians were urged to relocate from reservations into cities, into especially designated urban relocation centers, where it was thought there would be need for surplus labor. This policy of relocation was the brainchild of then Bureau of Indian Affairs Commissioner Dillon S. Myer. During World War II, Myer headed the War Relocation Authority, which managed Japanese-American internment camps.

The “termination and relocation” policy (described in Document 38) was very unpopular among Indians. President Kennedy put an end to it, but neither he nor Lyndon Johnson developed any policy to replace it. President Nixon ushered in the current policy of “self-determination,” encouraging tribes to govern themselves and allowing them to supersede Congressional authority in some areas. Most major environmental legislation, for instance, allows for tribal nations to be treated as states under these laws, meaning that they can set environmental standards on their reservations that are higher than the federal standards. Readers interested in the legal status of Native Americans should consult Appendix C, which charts changes in the rights and protections granted them from 1777 to 2020.

I gather the federal government remains “in the Indian business,” but its relationship with the tribes is now less contentious. Before, it seems conflict was the norm—from the beginning of European settlement in North America. Indians and settlers fundamentally disagreed on how the land should be used.

They differed in their concepts of land tenure. The English came with a preconceived notion that Indians did not engage in farming. In the international law of the time, farmers had a superior claim to land over hunters and gatherers (see Document 16). In reality, of course, tribes did engage in agriculture. Indians had to show the Pilgrims how to grow corn, a crop they had never seen. When John Winthrop made a speech claiming that Indians had no fixed abode and were constantly roaming over the land in search of game, he was standing on the deck of the Arbella, in England. He had not yet met any Indians. Once he and others stepped on American shores, they thought they saw endless virgin forests. Actually, Indians regularly used fire to burn the understory and clear out the forest floor so that they could get in there and hunt. As the historian William Cronon points out in Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England, what the Europeans found wasn’t endless forest; it was park-like savanna.

I’d say that in the very beginning of European settlement, relations between the Natives and the newcomers were friendly and cooperative. Then, when the colonists got powerful enough that they did not need the Indians as allies, relations became rancorous and there was conflict.

To what extent was the harm done to American Indians a deliberate policy, and to what extent a series of injustices is by private citizens that our laws failed to punish?

It’s certainly a combination. Policies have changed over time, obviously. The Europeans, and later the Americans, saw it as their destiny to occupy a continent. Some in the founding generation—perhaps George Washington, who discusses the issue in a letter to James Duane (Document 7)—thought they could work out an accommodation with the Natives. Thomas Jefferson thought it would take the new American republic forty generations to settle the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific. (It took only four.) Still, Jefferson conceived a plan to displace the Indians through the fur trade. He set up a series of government trading posts called factories (because the man who ran a post was called a factor), where Indians would come and exchange furs for trade goods. As game dwindled, the Indians became more dependent on these trade goods yet less able to pay for them. An Indian hoping to purchase an axe head, sack of flour and bolt of cloth might find himself three pelts short of the purchase price. The factors allowed Indians to take the goods on credit. Jefferson, anticipating this, said that eventually the Indians would incur debt in an amount they could only repay by sessions of land.

The removal of Indians from the southeastern United States during the 1830s was certainly deliberate policy. Later, the federal government devised the reservation system to protect Indians from white depredations as much as to protect settlers from Indian depredations. They considered the reservations temporary institutions, where Indians would learn to farm in the American manner, preparing them for citizenship as small landholders.

But the land set apart for reservations wasn’t always well suited for farming. Usually, it was land whites did not want. There were unrealistic expectations, also. Except for the Pacific Northwest, the western territory beyond the 100th meridian—where many reservations were sited—is prone to drought. But it was “scientific fact” in the 19th century that “rain followed the plow”—that breaking the sod of the prairies would cause it to rain. The remarkable thing is that from 1870 to 1930, this worked. We now know that these sixty years were the wettest in the history of the American West. In 1930, the rain stopped and you had the Dust Bowl.

Luther Standing Bear, an early 20th century Sioux writer, said “there was never wilderness here until the white man came.” Indians had managed North American forests and prairies in a way that sustained their population. They did this not out of some abstract idea of ecology, but because thousands of years of observation had taught them the boundaries within which they had to live so as to survive.

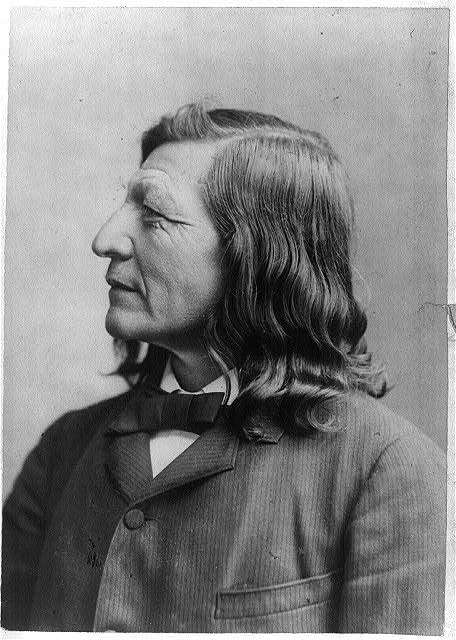

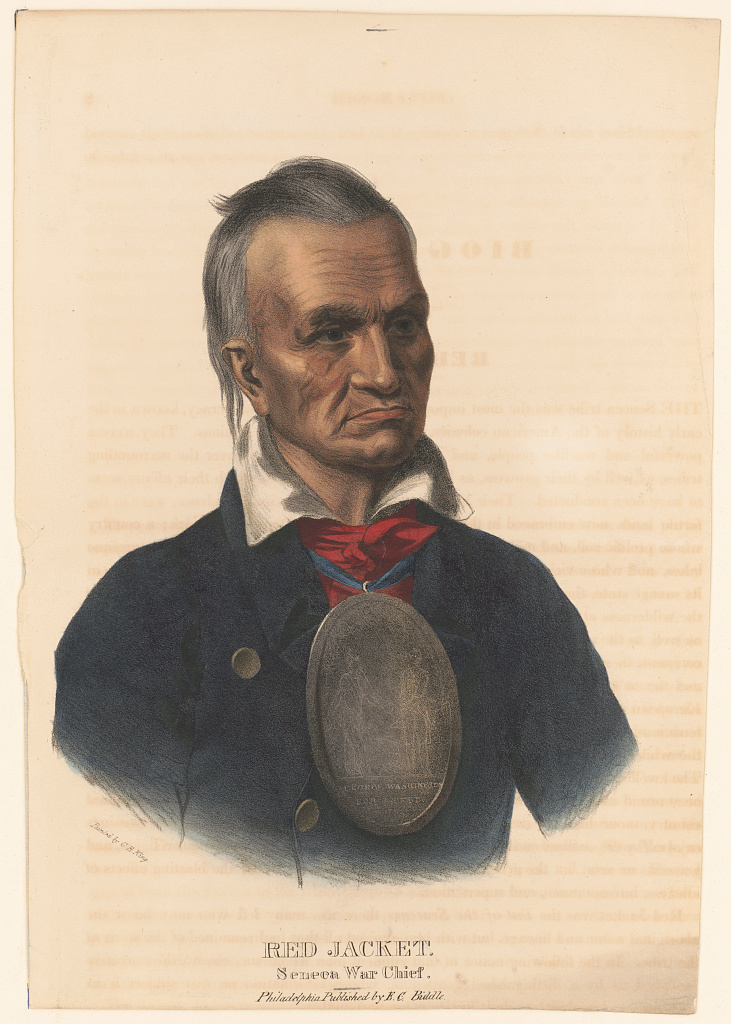

The Indians and the settlers also held fundamentally different religious views. I found Red Jacket’s critique of Christian teaching (Document 9) rather shrewd.

Red Jacket, who was a Seneca, became known for a series of disputations with Christian missionaries. In one of them, a missionary comes to a village and begins to tell the Biblical story, from creation through resurrection. When he finishes, Red Jacket says, “It’s a good story. Now, let us tell you ours”—and he begins to tell the Iroquois creation story. The missionary, incensed, leaps up, saying, “What are you doing? I give you eternal truths and you repay me with blasphemy!” Red Jacket, it is said, didn’t take offense. He simply replied, “Sir, you’re obviously not well schooled in the art of courtesy. We listened to your story and believed it. Why can’t you hear our story and believe it as well?”

For the missionaries, to convert to Christianity meant giving up prior practices, and exclusively practicing Christianity. It also meant converting to Western culture. Indians took a different view. Each tribe had its own traditions. They might fight each other; they might trade with each other or intermarry. But they never thought you had to convert another tribe to your way of believing. They practiced an easygoing pluralism. Each people received its instructions from the Creator, along with certain capacities. As long as everybody operated according to those instructions, everything would be okay.

At the end of your general introduction, you write “American Indians remain today a vital part of the story of the United States, as they always will be.” That’s a hopeful statement.

I am hopeful. Today there are six Native Americans serving in the House of Representatives, a record high. In Deb Haaland, we have our first Native American Secretary of the Interior. Under the policy of self-determination, native nations have gained a modicum of control over their own destinies. That can always change, of course. Any native victory is fragile and contingent. That’s why Native tribes have insisted on what may seem small or technical prerogatives. As the late scholar John Mohawk said, “If you want to be sovereign, you have to act sovereign.” In practice this means issuing tribal hunting or driving licenses, maintaining tribal police forces, and so on.

American Indians have always served in the United States Armed Forces in numbers disproportionate to their percentage of the population. For some, I assume, it’s the warrior tradition. Others found in military service a path to citizenship. Many see themselves defending the same rights as all American soldiers do. They have fought for the US without giving up their tribal identities. For example, consider Document 37 in the volume. The Haudenosaunee, also known as the Iroquois, were not citizens during World War One, and so were not draftable, although some chose to fight. By World War Two, they were citizens, yet refused to be drafted, saying it impinged upon their sovereignty. That impasse was settled when in January of 1942 the Haudenosaunee Confederacy separately declared war on Germany, Italy and Japan.