W. E. B. Du Bois and the Niagara Movement

A reconstruction of a conversation from late January 2002, my classroom, 2nd period AP US History, student’s name altered for privacy:

“Ms. Bryan, after Reconstruction, where did the Black people go?”

“Hmmm….Rosa, let’s think back to Tuesday. Do you remember our conversation about the Jim Crow laws in the South? Or about the creation of black towns in northeastern Colorado in the 1880s? Can you answer your own question?”

“Duh, Miss! You know I listen to you. But I’m talking about the book. Where are they? Other than the peanut guy, there aren’t any pictures of black people until Martin Luther King in Chapter 22. Why not?”

“Great question, Rosa! But are you sure? Let me take a look and I’ll get back to you. By the way, the peanut guy’s name is George Washington Carver. Now, today’s topic is the Populist Party platform of 1892. Everyone, find a partner and….”

And so I clumsily side-stepped my first serious reckoning with the missing voices of American history. I was 25; it was my second year of teaching and my first time teaching APUSH. I didn’t even realize that I needed to critically think about what I was teaching and why! But that moment with Rosa led me to an earnest re-appraisal of my teaching choices and materials. And so began my love affair with teaching with primary sources.

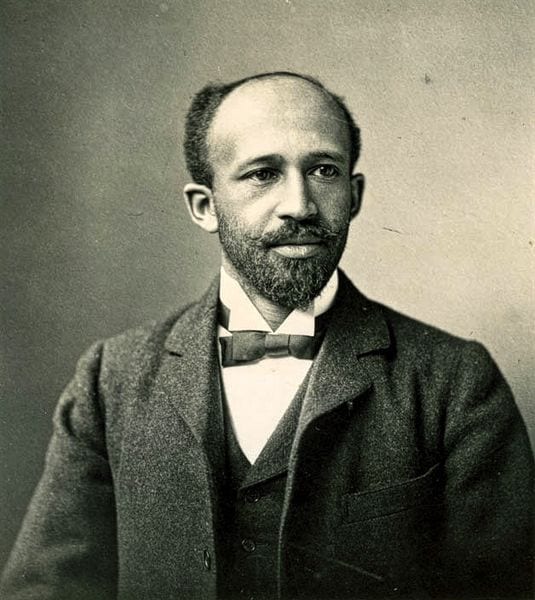

One of the authors I became heavily reliant upon was W.E.B. Du Bois. While his rivalry with Booker T. Washington is touched upon in most textbooks, I also found it useful to frame his contributions to the struggle for civil rights as part of a historical continuum that reached from Reconstruction to the Obama era. Teaching American History’s core document volume Populists and Progressives includes a classic illustration of Du Bois’ thinking regarding the methods and goals of the turn-of-the-century civil rights movement. Written in his capacity as National Secretary of the Niagara Movement, Du Bois’ “Address to the Country” illustrates the role that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments played in his understanding of civil rights. It argues the need for federal action to ensure Black access to civil rights and shows that such action would not occur without the grassroots activism of African Americans like himself.

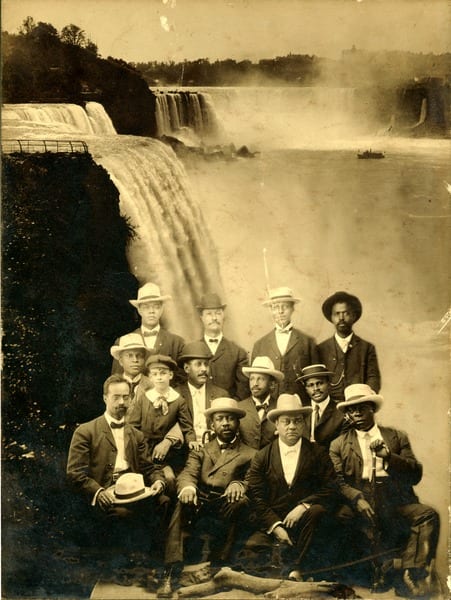

The brain-child of W. E. B. Du Bois and W. M. Trotter, the Niagara Movement held its first meeting in Fort Erie, Ontario, attracting twenty-nine African American activists. It resulted in the creation of a national organization. With anticipated chapters in all fifty states; standing committees on civil rights, crime, economic opportunity and interstate travel; and the twin aims of overturning segregationist policies in the South and the passage of state-level Civil Rights Acts in northern states, the organization embarked on a fervid membership and fundraising drive. The Niagara Movement grew rapidly and was poised to become the nation’s leading Black civil rights organization.

Prior to the Niagara Movement’s inception, the post-Reconstruction civil rights struggle had been led by Booker T. Washington. Founder in 1881 of the Tuskegee Institute, he was a proponent of industrial education. Arguing that self-improvement would lead to eventual security and prosperity for Black Americans, Washington explained his philosophy on civil rights in his 1895 speech at the Atlanta Exposition:

The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly. . . . No race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized. It is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours, but it is vastly more important that we be prepared for the exercise of these privileges.

The Niagara Movement’s call for “full manhood suffrage” and “the abolition of all caste distinctions based simply on race and color” was a flagrant departure from the accommodationist approach emanating from Tuskegee. In their 1905 “Declaration of Principles,” released after that first meeting in Fort Erie, the Niagara Movement brought to the struggle for African American rights a sense of urgency and insistence on personal agency that had been missing from Washington’s tactics. Writing that “persistent manly agitation is the way to liberty,” the Niagara Movement decried “[a]ny discrimination based simply on race or color,” regardless of “how hallowed it be by custom, expediency, or prejudice.”

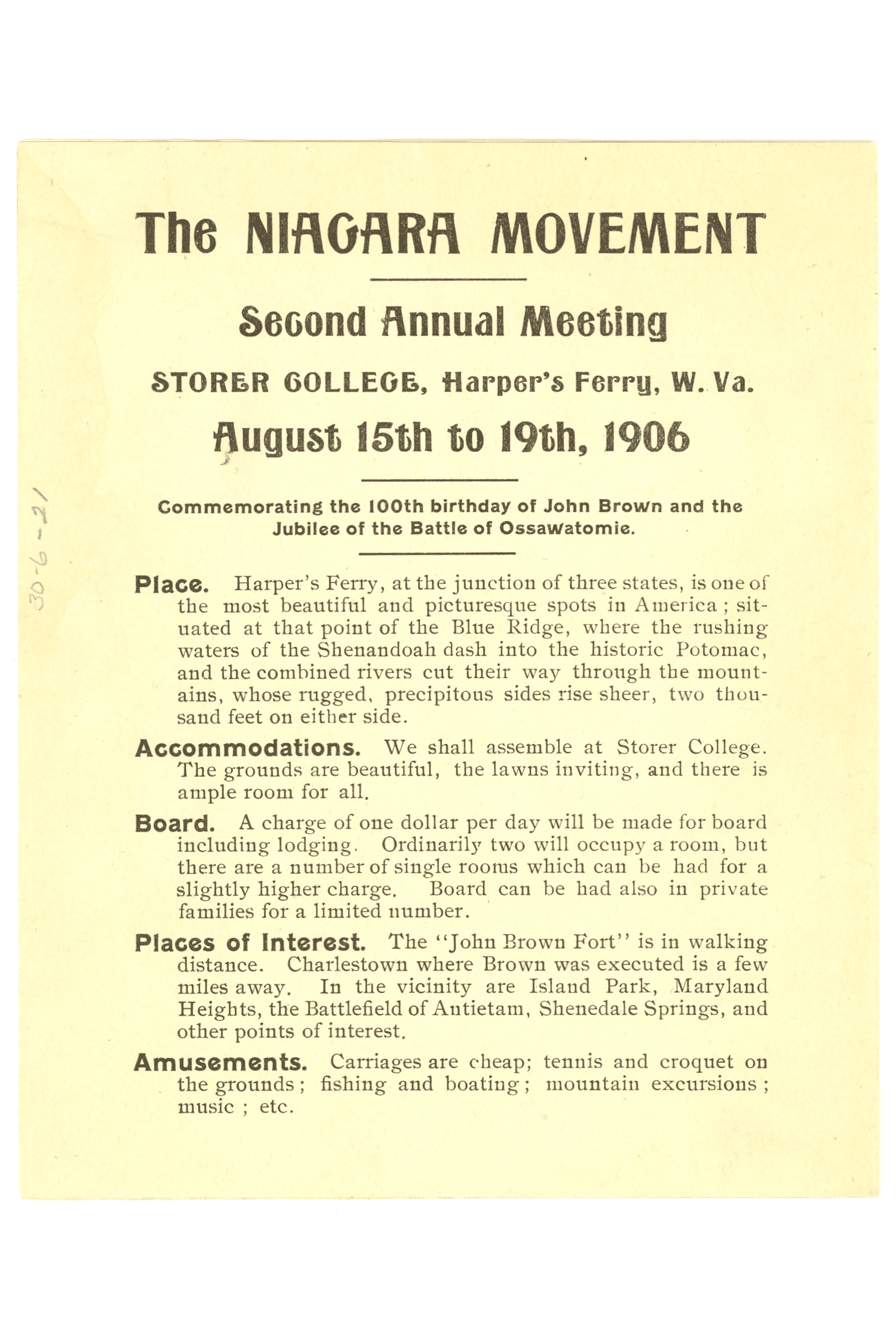

Du Bois’ “Address to the Country” further embodies the relative radicalism of the Niagara Movement’s purpose and methods. Written in the summer of 1906, it was the closing statement of the Movement’s second annual meeting. Held in Harper’s Ferry to commemorate the “100th birthday of John Brown and the Jubilee of the Battle of Osawatomie,” this event was the apex of the Niagara Movement’s influence and popularity. The “Address” was read aloud by L. M. Hershaw, the Washington D.C. secretary, and subsequently widely published in African American newspapers.

“Step by step, defenders of the rights of American citizens have retreated.” So wrote Du Bois in the opening paragraph of the statement. Throughout the piece, Du Bois attacked the failures of Black leaders, white society, the federal government and the Republican party to protect the rights codified in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Labeling segregated schools in the South “a disgrace,” he anticipated Brown v. Board of Education fifty years hence. He called on Congress to oversee congressional elections, foreshadowing federal intervention authorized by the 1965 Voting Rights Act. And he hammered home the need for federal protection of citizens’ Fifteenth Amendment rights, for “with the right to vote goes everything: Freedom, manhood . . . the right to work, and the chance to rise.” Calling discrimination within public areas “un-American, un-democratic, and silly,” he linked the federal government’s failure to ensure the right to vote for Black Americans to the discriminatory practices of state governments. These practices became the target of the grassroots activism seen in the Freedom Rides of 1961 and Freedom Summer of 1964.

Any student of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. will recognize his reliance on Du Bois’ careful balancing of federal action against individual activism. When Du Bois proclaims “We claim for ourselves every single right that belongs to a freeborn American, political, civil, and social,” the modern reader calls to mind King’s famous assertion on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in the summer of 1963:

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note. . . . This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men—would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

In the evolving role of the federal government in ensuring civil rights, the “Address” plays a key role. From the redefinition of citizenship in the Reconstruction era; to Du Bois’ cry “We want the Constitution of the country enforced” during Jim Crow; to the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of the 1960s; to modern debates about affirmative action—the questions have been constant. What is the role of the federal government in defining civil rights? How active should it be in ensuring access to those rights? The “Address” answers those questions, and Du Bois’ response resonates today.

Despite its lofty goals and Du Bois’ energetic leadership, the Niagara Movement imploded. In 1907, the debate over the role of women in the Niagara Movement deepened the internal conflict that aleady existed between state and national officers. The departure of original member William M. Trotter, founder of the influential African-American newspaper the Boston Guardian, led to negative publicity and a substantial decline in membership. The 1908 annual conference was divisive and poorly attended, and financial woes forced the organization to fold several years later.

While the leaders of the Niagara Movement were absorbed in internecine conflict, the Black residents of Springfield, Illinois became the latest victims of racial violence. On August 14th and 15th, 1908, a white mob destroyed the Black section of Springfield, lynching one man, murdering another, and destroying an estimated $150,000 in property. That the violence occurred in Lincoln’s adopted hometown shook activists to the core, renewing interest in a national civil rights organization. In 1909, white and Black advocates formed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). On their website, the NAACP directly attributes their founding goals to the work done by W.E.B. Du Bois and the Niagara Movement.