Nothing is New: Political Strife and Competing Worldviews in the 1790s

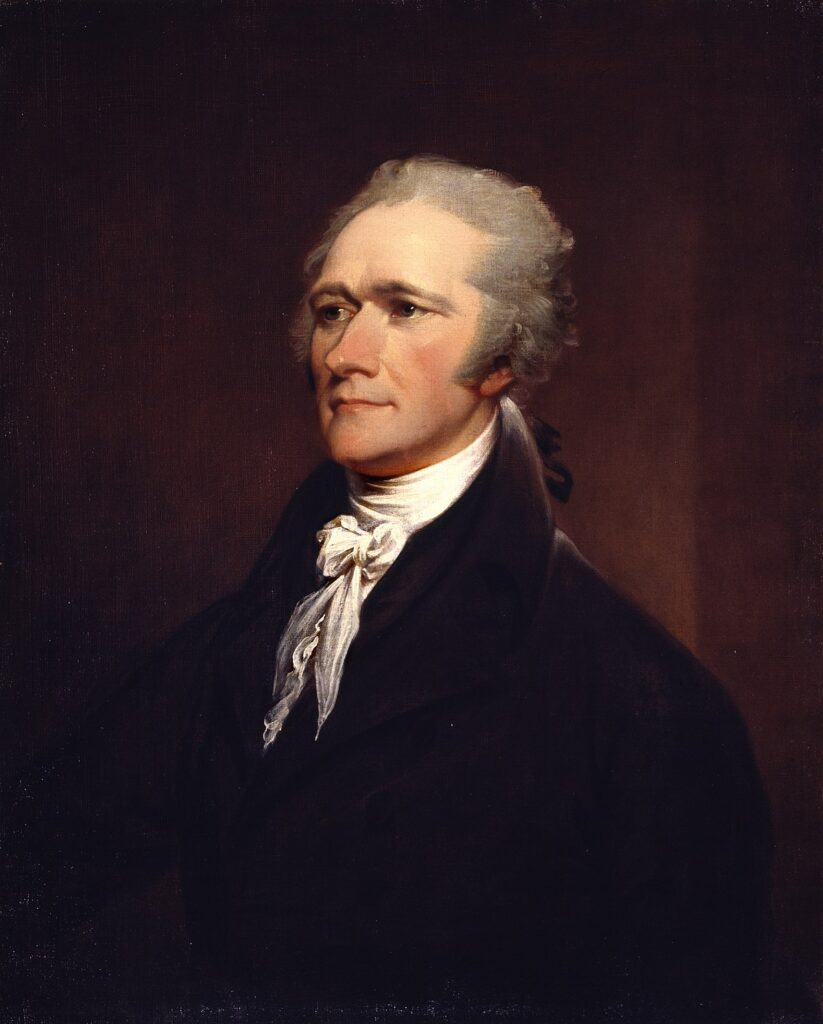

E Pluribus Unum, We the People, self-evident truths—these were the touchstones of the 1770s and 1780s. The historic collaboration between Alexander Hamilton and James Madison on the Federalist essays in the late 1780s quickly gave way to a political disagreement so sharp that it sundered US politics permanently into (at least) two rival parties. Hamilton’s Federalist Party and Madison’s and Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party formed over their fundamental disagreements regarding the nature of the US government and their visions for the nation’s future. Despite a strong Revolutionary aversion to factional politics, the intense personal and political animus between Hamilton and Madison’s closest friend, Thomas Jefferson, led to the hardening of a policy dispute into a permanent and highly consequential division in American politics. At the core of this division and rivalry was a tension within the Enlightenment’s intellectual milieu between liberal universalism and republican particularism. In a manner akin to the reversal of nomenclature seen in the Federalist-Antifederalist debates, Hamilton’s Federalists represented a more particularist republican understanding of the world, while Jeffersonian Republicans held a more universal liberal worldview. These competing worldviews involve far more than the common narrative of national government versus state government, so typically focused on in the disputes between Federalists and Jeffersonian Republicans, and permeate nearly all of the sociopolitical and cultural tensions and disputes of the 1790s and early years of the nineteenth century.

Given the claim that the Hamilton-Jefferson divide was founded on a dispute between “liberal universalism” and “republican particularism,” a brief exploration of these concepts is in order, as these are not concepts readily spoken of in contemporary America. Jefferson was undeniably a son of the Enlightenment, as were virtually all of the American Founders and Framers, but within the broad Enlightenment tradition exist various strands of thinking. As evinced by the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson was especially influenced by the thinking of John Locke, and the core tenets of Lockean liberalism—individual rights, limited government, a social contract, and liberty—are at the heart of Jefferson’s vision of the world and his poetic expression of American independence. For a great many Enlightenment thinkers and their successors like Jefferson, one of the great advances of the Enlightenment was its universalism; that is, the applicability of Enlightenment ideas to all people in all places at all times. Lockean liberalism was not merely an English concept developed by an Englishman for the English people, but instead a series of abstract principles applicable to all people. Jefferson’s appeals to a candid world and humankind in the Declaration of Independence imply that Jefferson was thinking of the philosophical principles of the Declaration of Independence not only in terms of the historical moment that was the American Revolution, but in terms of their universal appeal and applicability. Thus, Lockean liberalism really was universal, and this perhaps explains Jefferson’s fervor for the promise of the French Revolution and other global revolutions where liberalism would emancipate mankind from the dogmas of the past. Jefferson’s letter to Roger Weightman less than a fortnight before his death in 1826 attests to his lifelong commitment to this liberal universalism.

At the same time, the Enlightenment also contained a collection of ideas that political theorists and philosophers have come to call republicanism. The Federalist’s repeated references to republicanism, the Antifederalists’ preoccupation with republican virtues, Madison’s determination to find a republican solution to the ills of republican government, and the Constitution’s guarantee of republican government in Article IV, Section 4 demonstrate a broad commitment to republicanism by the Founders, as well. However, republicanism, rooted as it was in Aristotelian thought, was by its very nature particularist; that is, it was tied to civic participation and the virtues of a particular people in a particular polity, not an abstract and universal mankind. Republican particularism depended upon the specific qualities of a body politic in a way that liberal universalism did not, and thus issues of national sovereignty and identity were of greater concern to the republican particularists. The realist and nationalist political ideas of Alexander Hamilton make abundant sense when viewed through the lens of republican particularism, and like Jefferson, these were lifelong commitments. In 1774, a young Hamilton vented his outrage at British conduct in his A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress and grounded that outrage in the republican aversion to arbitrary coercion and demand for constitutional rights. He implicitly identifies an American polity of sorts and criticizes the lack of civic participation granted to Americans within the British system. Similarly, near the end of his life, in an essay called The Examination Number VII, Hamilton attacked Jefferson and his Republican Party for their support of mass immigration during the controversy over the Alien Act. Hamilton considered this a destabilizing invasion of people who did not share the particular American civic virtues that had developed here, and who would then dilute the strength of the civic participation of American citizens.

With these lifelong commitments to extremely divergent worldviews in mind, the fierce rivalry between Hamilton and Jefferson in the 1790s becomes clearer to the modern American. For Hamilton, the particular republican polity that he fought for was the United States and not simply one or some subset of the states. This polity was the most appropriate for preserving the liberties of all Americans, and it was this polity that needed to be respected and defended against the other polities of the world. Hamilton’s realist politics, his program for economic development, his favoring of Great Britain, the dominant global power and polity whose constitution was closest to ours, and his defense of immigration restrictions and safeguards to citizenship are all expressions of Hamilton’s commitment to republican ideals and conditions particular to the United States. For Jefferson, the universal promises of liberalism gave him a cosmopolitan view that drew him to the hype of the French Revolution and revolution in general. Simultaneously, universal liberalism’s distrust of government authority drove him to favor the rights and powers of the states, believed to be more accountable to the individual, over those of the federal government of the United States. Even in matters of religion, Hamilton demonstrated traditional Christian beliefs more in line with the republican virtues common to the early United States, while Jefferson meandered toward a more Universalist conception of Christianity favored by cosmopolitan liberal thinkers like Joseph Priestley.

In disputes of the era over the Bank of the United States, neutrality, or the Alien and Sedition Acts, the underlying rivalry between liberal universalism and republican particularism is present. While extremely contentious and stained with personal animus, the battle between these two men and their followers never boiled over into physical violence. Beyond a lens by which to understand their differences, perhaps the ultimate lesson of the worldviews of these two men is their common belief in political, that is, peaceful, resolution of differences. Regardless of which view modern Americans may adhere to, that lesson is one we can all agree with.

Interested in learning more about the political turmoil of the 1790s? Please join us for our November 8th webinar, “Jefferson: The Atheist?” or our December 13th webinar, “Jefferson: The Statesman.” You can learn more about our webinar series here.

Greg Balan is a 2016 James Madison Fellow for Florida, the 2022 State History Teacher of the Year for the Florida State Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and a proud MAHG graduate.