Peace is at Hand

We hear it all the time. Political pundits tell us that Americans are more politically divided than at any time since the Civil War. One exception may be the 1960s and 70s when the nation seemed irreconcilably divided over involvement in the Vietnam War.

Conservatives saw the war as one part of a worldwide struggle against international communism. They argued that the United States was in South Vietnam to defend an ally against a communist takeover by North Vietnam and its communist allies. Many embraced the so-called Domino Theory. If South Vietnam fell to communist North Vietnam, they maintained, Laos and Cambodia would soon follow, threatening Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Some conservatives, known as hawks, wanted the United States to be more aggressive in waging war. Other hawks were willing to negotiate if the United States maintained military pressure against North Vietnam.

Opponents of the war, known as doves, saw the war as a betrayal of American values. They saw the war as a nationalist struggle against colonial imperialism. Some demanded immediate withdrawal so the Vietnamese people could settle their differences without intervention from the United States. They argued that the United States had no strategic interest in South Vietnam and that it was governed by a weak and corrupt regime lacking public support. These factors convinced many that the United States could not win a clear victory. Therefore, further loss of American lives would be wasteful and unnecessary.

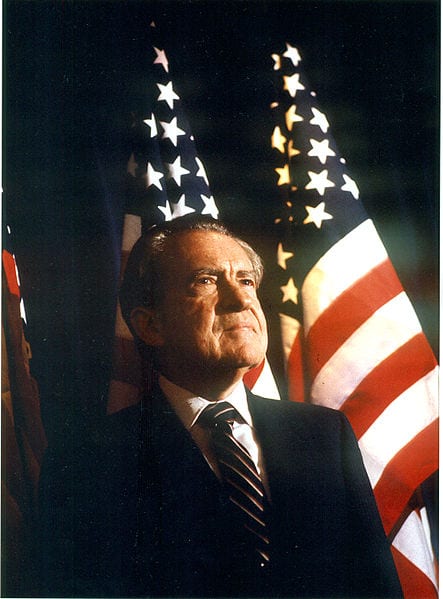

The domestic political battle lines were so hardened that when Dr. Henry Kissinger, President Richard Nixon’s National Security Advisor, addressed a news conference on October 26, 1972, and declared, “peace is at hand,” he was greeted with both relief and cynicism. Most Americans hoped Kissinger was delivering a frank and transparent assessment of the peace talks between the United States, South Vietnam, and North Vietnam. Cynics wondered if Nixon and Kissinger had conspired to lift American spirits in a classic October surprise—a late campaign ploy to boost Nixon’s reelection effort in the 1972 presidential campaign.

Most American history teachers focus on the role of US presidents when teaching political history. They are less likely to focus on the part played by a Secretary of State, much less a National Security Advisor—both jobs Henry Kissinger held in the Nixon/Ford administrations. Perhaps Henry Kissinger should be an exception.

Kissinger is a German-born Jewish refugee who fled Nazi Germany with his family in 1938 at age 15. (As of this writing, the 99-year-old Kissinger is the last surviving Nixon cabinet member.) After serving in the US Army in World War II, Kissinger earned a BA, MA, and Ph.D. from Harvard and began teaching at Harvard in 1951. He published a controversial book, Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy, in 1957, arguing that the United States should consider using tactical nuclear weapons in future wars. In 1968, the ambitious Kissinger consulted on foreign policy for Lyndon Johnson’s Democratic administration and advised the campaign of Nelson Rockefeller for the Republican presidential nomination. At the time, he called Richard Nixon “the most dangerous man running for president.” When Nixon won the Republican nomination, Kissinger set aside his differences and offered to do all he could to help Nixon win the presidency. Nixon rewarded Kissinger’s efforts by appointing him National Security Advisor. Kissinger was so well connected in Democratic and Republican circles that he might have received the same appointment had Nixon’s opponent, Hubert Humphrey, won the presidency.

President Nixon and Kissinger formed a surprising bond. Nixon was withdrawn and somewhat paranoid, while Kissinger is charming and worldly. Together they developed the administration’s strategy for “extricating” the US from Vietnam, with Kissinger assigned the role of chief negotiator in talks with the North Vietnamese. According to Kissinger’s account in his 1994 book, Diplomacy, although Nixon lacked confidence in the South Vietnamese regime of President Nguyen Van Thieu, he believed an unconditional withdrawal of troops would betray our South Vietnamese allies and damage US credibility around the world. Yet, he remained convinced that the US could not sustain its current level of involvement. Nixon settled on a three-prong strategy: negotiating with North Vietnam; maintaining military pressure on the North; and slowly replacing US troops with South Vietnamese troops, a process known as Vietnamization. Nixon sought public support for his strategy in a televised speech in November 1969. After summarizing his administration’s public negotiation positions, he called on the “silent majority” of American people to call the White House in support of his plan. The tactic worked. The White House switchboard reported an overwhelming response favoring Nixon’s strategy.

President Lyndon Johnson, Nixon’s predecessor, facing domestic political pressure from a growing anti-war movement in the United States, had agreed to peace talks with North Vietnam in 1967. However, the talks were moving at a glacial pace. It took nine months for the parties to agree on the shape of the table to use in their meetings. Kissinger began to look for a way to break the impasse. With Nixon’s approval, he began secretly meeting with his North Vietnamese counterpart, Le Duc Tho, in February of 1970, but the two negotiators made little progress until the summer of 1972.

This progress came about as a result of the failed North Vietnamese invasion of the South at the end of March 1972. North Vietnamese units had been operating in the South since 1964 and had conducted a large-scale invasion previously in 1968. Both the 1968 and 1972 invasions met with initial success but ultimately failed. In 1972, with many fewer U.S. forces in country, most of the fighting on the ground was done by the South Vietnamese. Still, American air power continued to be a significant factor in thwarting the North Vietnamese. By the summer of 1972, the South Vietnamese were retaking land lost earlier to the northern forces. In September, the South Vietnamese recaptured the important provincial city of Quang Tri.

Although a military failure, the invasion left the North with its remaining forces in South Vietnam in a better position to strike again. This led the north to seek an agreement in Paris, believing that as the U. S. continued its withdrawal, it would be able to conquer the South.

According to Kissinger’s account of the final peace negotiations in Diplomacy, the US position in the fall of 1972 was as follows. The United States would agree to “a ceasefire followed by a total withdrawal of American forces and an end to resupply and reinforcement of communist guerilla forces operating in South Vietnam,” known as the National Liberation Front. The political future of South Vietnam would be left to further negotiations between North and South Vietnam. The United States also insisted that all American prisoners of war be returned and North Vietnamese cooperation in accounting for Americans missing in action. North Vietnam’s goal was to reunite the country under their control and impose a communist order, so Le Duc Tho insisted on an unconditional American withdrawal and “the dismantling of the (South Vietnamese) Thieu regime” before any further negotiation. There the two sides stood on October 8, 1972, when Le Duc Tho surprised Kissinger and accepted “Nixon’s key proposals.” North Vietnam agreed to a ceasefire, returning US prisoners of war and leaving Thieu’s government in control of South Vietnam. Kissinger accepted on the spot, setting up a future struggle to gain Thieu’s endorsement.

In a news conference on October 26, 1972, Kissinger described the status of the United States’ negotiations with North Vietnam in considerable detail. But a straightforward sentence from Kissinger gave the press its headline. “We believe peace is at hand.” Kissinger summarized the positions both sides had agreed to, insisted that the United States’ approach was not influenced by the upcoming presidential election, and denied there was a large gap between the US views of the proposed agreement and those of the South Vietnamese. He reminded the press that the war had been waged chiefly in South Vietnam, so they had a legitimate say in creating a peace agreement.

South Vietnamese President Thieu now asserted himself in the negotiations. Thieu felt abandoned by Kissinger’s failure to keep him informed about his secret talks with Le Duc Tho. He protested the agreement’s provisions permitting North Vietnamese regular troops to remain in South Vietnam and pushed Nixon to continue the war. Nixon decided not to sign the deal without Thieu’s approval on-board. Instead, he increased the military pressure on Hanoi by launching a large-scale bombing campaign on December 18, 1972. Nicknamed “the Christmas bombing” by the press, the campaign’s goal was to reassure Thieu that Nixon was not abandoning his government to the communists and assure the communists that the United States was still committed to an independent South Vietnam.

Despite dropping more tonnage on North Vietnamese cities and military targets in eleven days than the United States dropped in 1969–1971, little changed at the bargaining table. North Vietnam reopened negotiations in January 1973 and signed the peace agreement on January 17, 1973. The agreement was only “cosmetically” different from that reached the previous October. Still, Thieu had agreed to the deal after Nixon assured him that he would respond forcefully to any violations by North Vietnam. Nixon was unable to keep his promise. When North Vietnam launched its final assault, Nixon was no longer President. His involvement in the Watergate scandal forced him to resign in August 1974.

In his book, The Vietnam War, historian Mark Atwood Lawrence argues that President Nixon had grown “frustrated and bitter” by his administration’s failure to end the war in his first term. Therefore, he “accepted” an agreement that “left the door open to future communist victory.” Just two days before the October 8 breakthrough in Paris, Nixon met with Kissinger in the Oval Office. Kissinger was convinced that North Vietnam was willing to settle the conflict “On close to our terms. But—I also think that Thieu is right, that our terms will eventually destroy him.” That eventuality became a reality in 1975 when North Vietnamese troops overran Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, and reunited Vietnam under a communist regime. Tragically, the most the agreement accomplished was, in Kissinger’s words, “a decent interval” in which South Vietnam could prepare for what the United States and South Vietnam predicted—a final assault by the North Vietnamese army.