Reconstruction on Trial

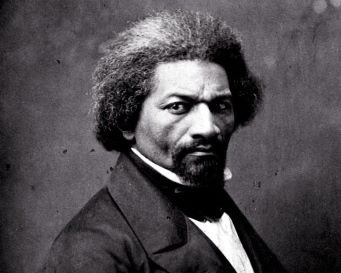

In September 1866, Frederick Douglass became one of the first black American delegates to a political convention.

What was the Southern Loyalist Convention?

Frederick Douglass was not expected to be in Philadelphia that September of 1866. His selection as an honorary delegate from Rochester, NY, surprised the Southern Loyalist Convention organizers, who were convinced that President Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction policies had failed. They gathered in the “City of Brotherly Love” to debate alternative approaches to the enormous challenge of Reconstruction. They met just three weeks after a similar convention – the National Union Convention – met in Philadelphia to marshal support for the President and his supporters campaigning for congressional seats that fall.

The plan called for a convention, comprised of only Southerners who remained loyal to the Union before, during, or after the Civil War, to suggest alternative Reconstruction policies. In a bid for greater national unity, the organizers invited border states to send delegates, and several northern states selected sympathetic spokesmen to travel to Philadelphia to play supporting roles. Douglass had been appalled to learn that former Union general Darius N. Couch marched into the National Union Convention alongside South Carolina Governor and former confederate senator James Orr. Douglass was learning that Johnson and his supporters were willing to sacrifice African American rights for a peaceful reunion with former confederate whites.

Why did Frederick Douglass attend?

Douglass’s presence as a spokesman for Northern opinion was unwelcome news for convention organizers and their Congressional supporters. Even Radical Congressman Thaddeus Stevens urged Rochester Republicans not to send Douglass. He feared that the influential African American leader’s presence would show that Congressional radicals secretly wanted social equality for African Americans. Stevens was concerned that this perception might cost radical Republicans in that November’s congressional elections, weakening the opposition to Johnson. His opinion may explain why there was only one black delegate – P. B. Randolph of Louisiana.

Frederick Douglass was not backing down. He said upon leaving Rochester, “If this convention will receive me, this event will be significant progress. If they reject me, they will only identify themselves” with Johnson’s National Union. When approached by fellow passengers on the train to Philadelphia asking him not to attend the convention, Douglass swore that nothing short of his assassination would prevent his attendance. In his autobiography, Life and Times, Douglass explains his reasoning. “Not to have participated, would contradict the principle and purpose of my life,” Douglass wrote. Douglass likely took note of the irony – that the opposition to his presence came from allies in the fight for racial justice.

Yet, as Douglass stood outside Philadelphia’s National Hall, hoping to march with fellow delegates to Philadelphia’s historic Independence Hall, all but one representative ignored him. That exception was

Theodore Tilton of New York, who noticed Douglass standing alone and greeted him “like a brother.”

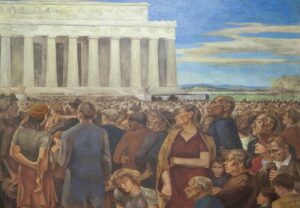

The two men – one white and one black – locked arms and joined the marchers walking east on Chestnut Street.

Somewhere along the route, Douglass noticed a familiar face belonging to Amanda Auld Sears, whose father was once the legal owner of Frederick Douglass’s body. Now they greeted one another like childhood friends. According to Douglass’s account in Life and Times, he asked Mrs. Sears why she was in Philadelphia. “I heard you were here, and I came to see you walk in this procession,” she replied.

What can we learn about Reconstruction from the Convention?

This brief encounter may serve as a metaphor for African Americans’ struggle for full civil and political rights during and after Reconstruction. Douglass, perhaps the most famous African American in the world in 1866, greeted the daughter of his former enslaver in the “Cradle of Liberty” while facing criticism that he was demanding too much, too soon. The history of Reconstruction proved that it was one thing for two childhood friends to see themselves as fellow travelers toward a more just society and another to translate that vision into national policy.

Perhaps Reconstruction Era Americans can be forgiven for thinking change was happening too quickly. Consider the dizzying sequence of events between mid-1864 and the competing conventions of 1866. President Abraham Lincoln, concerned that he would not be re-elected in November, 1864, removed Vice-President Hannibal Hamlin from the Republican ticket and replaced him with the loyalist southern governor, Andrew Johnson. Then General William T. Sherman’s dramatic capture of Atlanta, GA, helped propel Lincoln to a second term. Confederate general Robert E Lee surrendered the principal rebel army on April 9, 1865, just five days before an assassin fatally wounded Lincoln at Washington’s Ford Theatre.

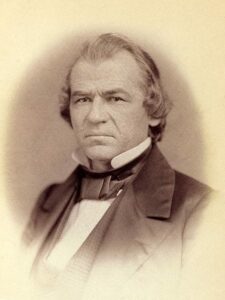

Suddenly, a new, inexperienced, and politically inept President assumed the task of reuniting the nation. In his Introduction to Teaching American History’s Core Document Collection volume, Reconstruction, Boise State Political Scientist Scott Yenor summarized the challenges facing Johnson this way: It should have been “a time for reconciling the North and South, bringing the formerly rebellious Southern governments back into their proper relation with the union, and protecting the basic civil rights of freedmen, blacks, and Unionists in those Southern states.” Yenor points out that each one of these challenges was daunting. Conquering all three – at the same time? Insurmountable. The pro-Union southerners meeting in Philadelphia that September had first-hand experience coping with the trauma the white southern majority felt. They likely understood, better than most Americans, how controversial Reconstruction policy would become.

What was President Lincoln’s approach to Reconstruction?

President Lincoln recognized the challenges Reconstruction would pose before the war ended. His December 1863 Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction was notable for its leniency. Lincoln called for seceding states to reenter the Union when only 10 percent of those citizens who voted in the 1860 election – with some exceptions – swore loyalty to the Union. He announced a blanket pardon and the restoration of all property, except enslaved “property,” for southerners who had not served in the confederate military or government. Congressional Republicans pushed back by passing the Wade-Davis Bill, which demanded that 50 percent of southerners pledge loyalty to the Union before implementing steps to create a new government in their state. Lincoln pocket-vetoed this bill. Reconstruction policy remained unsettled when Andrew Johnson took office following Lincoln’s death, although at the end of his life, Lincoln expressed a willingness to grant black suffrage to “the very intelligent, and those who served our cause as soldiers,” a position Andrew Johnson never adopted.

How did President Johnson’s approach to Reconstruction differ?

President Johnson issued his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction on May 29, 1866, which was similar to Lincoln’s in its leniency. In his proclamation, Johnson did not address black suffrage or protection for black civil rights. Those omissions would prove to be significant issues in the Southern Loyalist Convention. Johnson also vetoed the Freedmen’s Bureau bill and the Civil Rights bill of 1866, and urged southern states not to ratify the 14th Amendment, passed by Congress, to ensure civil rights for the formerly enslaved people. His actions convinced the southerners attending the Philadelphia convention that Johnson’s policy was a failure. Johnson’s refusal to protect black rights created a volatile condition for blacks and whites. Both were subjected to violent marauders. What many of the delegates wanted was peace and security. Johnson seemed incapable of delivering either.

In what ways did the Southern Loyalist delegates oppose Johnson’s Reconstruction plan?

The Southern Loyalist delegates discussed three significant issues: President Johnson’s Reconstruction policy, his opposition to the 14th Amendment, and African American enfranchisement. That last issue proved to be the most controversial. As Douglass relates in Life and Times, delegates from the deep South supported black suffrage. The African American population in 1866 was concentrated in the South, especially the deep South. If the Southern loyalists were to have any chance of effecting Reconstruction policy, they needed the votes of African Americans in the region. The border states, by contrast, had relatively low numbers of African Americans living in their states. Combining the votes of loyalist whites with the formerly enslaved would not significantly alter the political landscape.

In his biography of Douglass, historian David Blight reports that Douglass was invited to speak to the southern convention delegates by a chorus of voices chanting, “Douglass! Douglass! Douglass!” Douglass recalled responding to the chants “with all the energy of my soul.” He wrote in Life and Times that he “looked upon suffrage for the Negro as the only measure which would prevent him from being thrust back into slavery.” In his convention speech, Douglass said that African Americans asked “a right to all the different boxes – the witness box, the jury box, and the ballot box,” drawing cheers and appreciative laughter from his audience. Only such access would allow blacks to escape the “bad box” they currently inhabited.

Black enfranchisement was a bridge too far for the border state delegates. They boarded trains for home, abandoning the convention to the deep South delegates who quickly endorsed black male suffrage.

The study of Reconstruction affords students of American history a unique opportunity to debate the successes and failures of Reconstruction. The documents in Teaching American History’s Core Document Collection, Reconstruction, and others on our website help students understand the choices critical actors in the era made, why they made them, and the long-term consequences of those choices. Studying these documents will help students decide for themselves whether Reconstruction was a success and – if we are lucky – generate new questions to ponder.

Ray Tyler was the 2014 James Madison Fellow for South Carolina and a 2016 graduate of Ashland University’s Masters in American History and Government. Ray is a former Teacher Program Manager for TAH and a frequent contributor to our blog.

Want to learn more about Reconstruction and its role in American history? Join us on October 1, 2022 for our Saturday webinar about Reconstruction and the Declaration of Independence.