Secrecy Encourages Careful Deliberation

A Lesson from the Founders for Constitution Day

Americans in our day think “transparency” in government essential to its efficient and wholesome operation. The delegates to the Constitutional Convention did not entirely agree. They understood that secrecy encourages careful deliberation and compromise in the political arena.

Most of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention understood how precariously their new nation stood together, and how important it was to deliberate and compromise during that fateful summer. Thankfully, the delegates established ground rules for communicating with each other that helped to ensure the success of their meeting. We could learn an important lesson from the founders when thinking about our Congress today.

Secrecy Rules at the Convention

One of the Convention’s first decisions was to adopt secrecy rules. The delegates agreed “that no copy be taken of any entry on the journal…and that nothing spoken in the [Convention] be printed, or otherwise published, or communicated without leave.”

As John Kaminski has written, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention thought this was appropriate because it would promote deliberation and careful consideration of issues. As James Madison explained to Thomas Jefferson, the Convention thought secrecy would be “expedient in order to secure unbiased discussion within doors, and to prevent misconceptions and misconstructions without.” He wrote to James Monroe that the rule would “effectually secure the requisite freedom of discussion” and “save both the Convention and the Community from a thousand erroneous and perhaps mischievous reports.”

These remarks suggest that the delegates saw several critical benefits from a rule of secrecy during legislative debate. First, such a rule enables members to speak freely to each other while on the floor of the chamber. If members fear that their statements will be made public in order to turn public opinion against them, they will no longer discuss their ideas openly or seek to persuade each other. This would turn the whole meeting into a debating club, not a deliberative assembly.

Second, a public record can be manipulated by “mischievous” people to produce “misconceptions and misconstructions” in the public mind. The public may not read the journals and the debates, but they will read reports about them from people who can selectively quote those materials to distort what’s actually happening. To put it in today’s vernacular, reporters can take remarks “out of context” to turn the public against individual members and their proposals.

Later in his life, when reflecting on the secrecy rule, Madison described a third benefit. As he recollected, while the Convention was in debate, “the minds of the members were changing,” and if members had “committed themselves publicly at first, they would have afterwards supposed consistency required them to maintain their ground.” Keeping the deliberations secret, Madison maintained, ensured every member was “open to the force of argument” and able to change their minds freely. A secrecy rule allows representatives to listen to the arguments of others without being accused of “flip-flopping.”

We do not know whether the Convention would have been successful without a secrecy rule, but it is clear that the delegates thought the rule essential. Madison believed that “no Constitution would ever have been adopted by the convention if the debates had been public.”

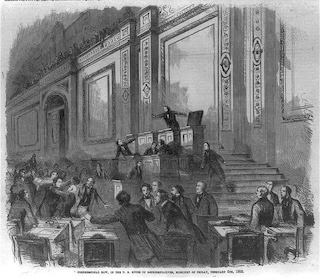

The Moderate Approach of the Early Congress

The U.S. Congress took a moderate approach to secrecy in its early years, balancing the benefits of transparency and secrecy. While the Constitution mandates that “Each House shall keep a journal of its proceedings, and from time to time publish the same, excepting such parts as may in their judgment require secrecy,” these journals merely record actions taken rather than the entirety of floor debates. Since 1794, both the House and the Senate have been open to visitors who wish to watch debates from the galleries, and debates have been published in various outlets such as the Congressional Record (since 1873). However, much of the discussions in committee rooms, cloakrooms, and elsewhere were still private, preserving the benefits of secrecy.

Transparency “Reforms” in the 1970s

Reforms in the middle of the 1970s abandoned this balanced approach. The 1970s brought in a wave of new members who, in the words of one member, “destroyed the institution by turning the lights on.” In 1973 the House prohibited closed committee hearings (the Senate did so in 1975). In closed session, committees can hear expert testimony from and ask questions of expert witnesses, and consider their recommendations. When the doors are thrown open, members feel pressured to perform for the audience, seeking to embarrass the witnesses and other members of the committee.

Reformers also took advantage of a provision of the 1970 Legislative Reorganization Act that allowed for public roll call voting. Prior to 1970, most of the votes cast in the House of Representatives were unrecorded, and thus essentially secret. Once these votes became public, members began to force “messaging” votes that were intended not to make law, but to put their political opponents “on record” for the next election. This practice has increased animosity, polarization, and vitriol in Congress.

The introduction of C-SPAN completed the transparency reforms of the 1970s. The network first began broadcasting House proceedings in 1979, and the Senate in 1986. It also covers most committee hearings. As Yuval Levin has recently written, the introduction of cameras has “turned all of Congress’ deliberative spaces into performative spaces, leaving less and less time for members to speak and work in private. The most obvious consequence of this transformation has been the explosion of grandstanding in both chambers.” Today’s committee hearings and floor debates in Congress are opportunities for members to score political points, or go viral on social media, but not to deliberate, persuade, or compromise with each other.

Recovering the Lesson from the Founders

Members are aware of the problems these transparency reforms have produced. One of them, a first-term member from North Carolina, has recently spoken out. In his experience, he writes, “The same people who act like maniacs during the open [committee] meetings are suddenly calm and rational during the closed ones. Why? Because there aren’t any cameras in the closed meetings.”

Thankfully, there are still places where members can work together on lower-profile issues, where there isn’t enough controversy to attract media. (Some playfully refer to these places as “Secret Congress.”) These places provide useful illustrations of the fact that, when they are given a little bit of space and secrecy to work together, people of different political views can still find common ground in this country on many issues. Many Americans are frustrated with Congress’s inability to compromise or agree on anything. But they typically overlook the role that these transparency reforms have played in producing this outcome. The members of the Constitutional Convention would not have been surprised, and they would counsel us to let our elected officials talk more to each other and perform less for us.

Joseph Postell is Associate Professor of Politics at Hillsdale College and a faculty member in the Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) program at Ashland University. In MAHG, Postell often teaches courses on Political Parties and on the US Congress. During the 2024 summer residential program, he delivered the Sunday evening lecture, “After Party: The Roots of Congress’s Dysfunction.” He also edited TAH’s core document collection, Congress (2020). Postell studies American political institutions and their relationship to the modern administrative state. He is the author of Bureaucracy in America: The Administrative State’s Challenge to Constitutional Government (University of Missouri Press, 2017) and coeditor of, among other volumes, American Citizenship and Constitutionalism in Principle and Practice (with Steven F. Pittz). Professor Postell is an alumnus of Ashland University, where he was an Ashbrook Scholar.